*The following is part of a series of blog posts researched and written by Mark Clardy, SRM Docent and independent scholar.*

Soundtrack of the American West

Final Movement

The Last Round Up

Well, pardner, fall is almost here, and we’ve reached the end of the trail. It’s been a while since we opened the gate to this musical rodeo, but there’s still so much more to the music of the American West. Maybe we have time to listen to one more cowboy song before we wrap up the series: “The Last Great Roundup”.

In this final post for the series, we’ll rope some mavericks that we missed along the way, and then we’ll take a look back at what we’ve heard along the trail before we say, “¡Adios!”

Mavericks Along the Trail

In every round up, there were always a few mavericks – stray unbranded calves – that were found and added to the herd. So in this final Movement of our Soundtrack of the American West, we have a few mavericks to take care of. That is, there are some Sid Richardson Museum blog posts from the past few years that we can now brand with some musical post-scripts.

Charles M. Russell | Captain William Clark of the Lewis and Clark Expedition Meeting with the Indians of the Northwest | 1897 | Oil on canvas | 29.5 x 41.5 inches

Sometimes, Charlie Russell liked to move the main players out of the way, and instead showcase characters in his paintings who are typically overlooked people. York, an enslaved member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804-1806), is portrayed in this painting with a commanding presence (see York: Of Myth and Fact). This was one of eight Charlie Russell paintings owned by Robert Vaughn, an older neighbor and good friend of Charlie’s.

Sometimes, Charlie Russell liked to move the main players out of the way, and instead showcase characters in his paintings who are typically overlooked people. York, an enslaved member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804-1806), is portrayed in this painting with a commanding presence (see York: Of Myth and Fact). This was one of eight Charlie Russell paintings owned by Robert Vaughn, an older neighbor and good friend of Charlie’s.

“Lewis and Clark’s Trail” (1905) is a song written by Robert Vaughn for the historic Expedition’s centennial celebration; and since he owned the painting, he used it for the cover of his sheet music. The song, however, does not mention York in any of its dozen verses. Charlie was also a creative writer and poet, and wrote a poem for Robert Vaughn in June 1911; Vaughn responded with a poem of his own, “Charles M. Russell, The Cowboy Artist” at a banquet for Charlie in July 1911 (Ann Morand, Your Friend, C. M. Russell: The C. M. Russell Museum Collection of Illustrated Letters, 1996, p. 54-55.)

Charles M. Russell, Buffalo Bill’s Duel With Yellowhand, 1917, Oil on canvas, 29 7/8 x 47 7/8 inches

After the Wild West was no longer so terribly wild, the “Wild West Shows” thrilled huge audiences with re-enacted scenes that were based (loosely) on events in the not-too-distant western past. One of the most famous of the Wild West Shows was put together by Buffalo Bill, and featured his encounter with Yellow Hair (or, as his name has been erroneously translated, “Yellow Hand”) as depicted in this painting (see The West Personified Across the World).

After the Wild West was no longer so terribly wild, the “Wild West Shows” thrilled huge audiences with re-enacted scenes that were based (loosely) on events in the not-too-distant western past. One of the most famous of the Wild West Shows was put together by Buffalo Bill, and featured his encounter with Yellow Hair (or, as his name has been erroneously translated, “Yellow Hand”) as depicted in this painting (see The West Personified Across the World).

“At That Bully Wooly Wild West Show” (1913) is a song about a man taking his date to a Wild West show, which seems to have served the same purpose as a horror film decades later.

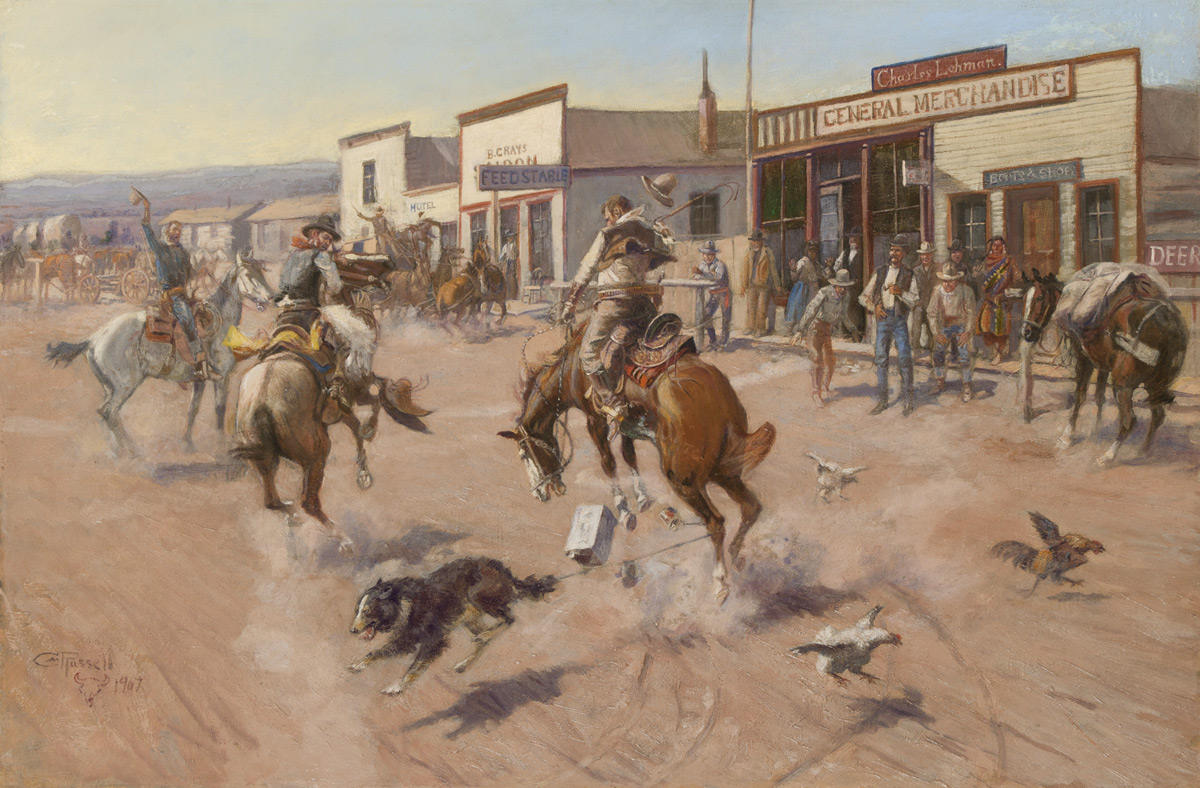

Charles M. Russell, Utica (A Quiet day in Utica), 1907, Oil on canvas, 24 1/8 x 36 1/8 inches

Again, Russell frequently showcased people in his paintings who often go unnoticed. One such person was Millie Ringgold, the Black woman in Utica. She had actually died the year before Russell painted this, but he included her anyway, as she was a well-known figure in the area. One of the things that Millie was known for was her ability to make better music singing and drumming on an empty oil can, than most people could on a piano. So Russell also included her oil can drum – the very prominent boxy can between the dog and the bucking horse (see Millie Ringgold and “Coal Oil Johnny”; and Millie in Montana).

Again, Russell frequently showcased people in his paintings who often go unnoticed. One such person was Millie Ringgold, the Black woman in Utica. She had actually died the year before Russell painted this, but he included her anyway, as she was a well-known figure in the area. One of the things that Millie was known for was her ability to make better music singing and drumming on an empty oil can, than most people could on a piano. So Russell also included her oil can drum – the very prominent boxy can between the dog and the bucking horse (see Millie Ringgold and “Coal Oil Johnny”; and Millie in Montana).

“Coal Oil Tommy” was one of Millie’s favorite songs, from a musical comedy called The Lottery of Life by John Brougham in about 1870. It was based (not so loosely) on the life of the very famous real-life profligate rags-to-riches-to-rags millionaire, John Washington Steele (1840-1920), aka, Coal Oil Johnny.

Frederic Remington, Among The Led Horses, 1909, Oil on canvas, 27 x 40 inches

Remington was drawn to the manly images of military life, at least until he viewed soldiers in action (and inaction) during the Spanish-American War in 1898 (see Illustrating Disillusions of War). He did, however continue to paint scenes of soldiers set in previous decades in danger on the plains, as in Among the Led Horses.

“The Regular Army O!” is a Broadway song by Edward Harrigan and David Braham with the distinct sound of an Irish jig – particularly when performed in a Traditional Irish Session. The song became very popular among the U. S. Army troops during the Indian wars at the end of the 1800s.

Well, that’s the last song in this roundup. Let’s take a look back at the trail.

Our Trail Diary

This blog series has been a musical exploration of Sid Richardson Museum’s collection of Western art, with each post pairing the paintings at the museum with one or more pieces of music, which may be heard on Noteflight.com, a music publishing website affiliated with Hal Leonard Publishing Co. The music may either be followed as it plays on Noteflight, or it may be heard as background music while examining the museum paintings online.

What a ride this has been! During this series, we have “listened” to a total of forty paintings at the Sid Richardson Museum, and 106 songs!

A cowboy would sometimes write in a journal as he went up the trail, if he was literate (see Cowboy Journals and the Art of Handwriting; The Cowboy Chronicles). So here is a “trail diary” of where we’ve been:

The first blog introduces the scope of the series and its “Symphony” format. Each Symphony covers a broad topic which may be spread over several blogs or “Movements” within the larger Symphony. This introductory blog also introduces the Symphony of Native America, and concludes with its first Movement: The Métis Buffalo Hunters.

Symphony of Native America

Charles Wakefield Cadman was the most prominent composer of the Indianist Movement of the early 1900s. This blog covers the tribal music origins and artistic connections of his 1907 publication, Four American Indian Songs.

Coinciding with the exhibition of five buffalo hunt paintings at the Sid Richardson Museum, this blog introduces the music of several Plains tribes as transcribed by early musicologists, follows the ceremonial nature of the hunt, and concludes with a ragtime buffalo “Coda”.

This blog presents the music of three tribes of the American Southwest: Apache, and Tohono O’Odham (formerly “Papago”), and Zuni. Both tribal and Indianist compositions are paired with museum paintings.

Symphony of the Cowboy

“A Cowboy Chorale”

The first cowboy music blog, “A Cowboy Chorale”, opens with the “N Bar N Waltz” from a ranch with connections to Charles Russell. It continues with the history of the American Cowboy (including the author’s cowboy connection) and several songs that the cowboys actually sang. A Coda provides a worksheet for composing your own verses for an old favorite, “The Old Chisholm Trail.”

Eventually, American composers began to arrange cowboy tunes, and to use the melodies in their compositions.

The cowboy began as the lowest man on the proverbial totem pole – dirty, intemperate, and of questionable character. But as interest grew in stories, books, and plays set in the West, he experienced a cleansing, almost spiritual ascension. Eventually, the cowboy became the newest American hero: pure, chaste, and righteous, exemplifying the best of American manhood. These are the songs of his unlikely rise to prominence, from stage and film, ragtime and blues.

The Artists’ Playlists

Charlie Russell and Frederic Remington were both men of their time, and were well acquainted with the music of their era. These are some of the songs that they mentioned in their letters and stories. The next two blogs were, essentially, their “playlists”.

Other Artists, Other Voices

The most well-known artists of the American West were Charles Russell and Frederic Remington. This post examines the musical context of works by the other Western artists at the Sid Richardson Museum.

This blog presents some songs of the Mexican vaqueros, the first cowboys in North America, and some songs about the vaqueros. Smuggling has always been an issue at the border, and is a common subject of Mexican corridos or ballads.

End of the Trail

- The Last Roundup (i.e., this blog)

¡Gracias y Adios, mis Amigos!

So we’ve rounded up the last few mavericks, and looked over our trail diary one last time. There’s just one thing left to do.

I would like to thank…

…All my advisors for their assistance, review, comments, & suggestions:

- Timothy D. Watkins, Associate Professor of Musicology at the TCU School of Music, Ft. Worth, Texas.

- Judith Gray, Folklife Specialist at the American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, Washington, D. C.

- Luis E. Coronado Güel, Ph.D., University of Arizona, Tucson.

- Janet L. Sturman, Ph.D. (Ethnomusicology), University of Arizona, Tucson.

…Leslie Thompson, Director of Adult Programs, and the Sid Richardson Museum for indulging me on this musical trail ride. The museum staff has always encouraged the docents to follow our varied interests as we interact with the art at the museum and with our visitors.

…My wife Sara for her proofreading, and the rest of the family for their understanding and patience when I disappeared, too frequently, into Noteflight or under a pile of old sheet music.

So, pardner, this is the end of the trail. I often end my school tours at the Sid Richardson Museum with a tune on a Native American Flute, so let’s listen to one last song. This is an Ojibway tune from Frederick R. Burton’s American Primitive Music, 1909: “Ojibway Farewell”

As Roy Rogers always sang…

Leave A Comment