*The following is part of a series of blog posts researched and written by Mark Clardy, SRM Docent and independent scholar.*

Soundtrack of the American West

Symphony of the Border

Sinfonía de la Frontera

¡Hola, mis amigos, y bienvenidos a la sinfonía de la frontera!

For this symphony of the border, we turn our attention to the southwest to hear the music of the Mexican borderlands. We will listen to las canciones de los vaqueros (songs of the Mexican cowboys), and los corridos de las contrabandistas de la frontera (ballads of the border smugglers). Many of these songs are available online in various versions as modern (copyrighted) recordings, but few of them were transcribed, arranged, or published prior to 1927, except for those that were published, lyrics only, in broadsides (large, single sided printing) or in newspapers. Therefore, most of the Noteflight links in this blog are my own arrangements based on the available later published melodies. Also keep in mind that there are often many variant lyrics and verses, just as there are with American cowboy songs.

The music we will hear is from a particularly turbulent era in Mexican history. We begin during the period known as the Porfiriato (1876-1911) which was the presidency – or dictatorship – of Porfirio Díaz (1830-1915). The music continues through the decade-long Mexican Revolution which lasted until about 1920. Prohibition began in the U. S. at that time, bringing problems anew to the borderlands. A quote, attributed to Díaz, expresses a commonly held sentiment south of the border:

¡Pobre México! Tan lejos de Dios y tan cerca de los Estados Unidos.

Poor Mexico! So far from God and so close to the United States.

I would like to thank two experts on Mexican music at the University of Arizona in Tucson for their suggestions and help with this blog. Luis E. Coronado Guel, Ph.D. provided a great deal of history, context and online resources for the corridos about smuggling along the border. Janet L. Sturman, Ph.D. (Ethnomusicology) pointed me in the right direction and provided information about modern Mexican classical composers who made use of traditional Mexican music in their compositions. For more information on the music – and history – of Mexico, see Dr. Sturman’s The Course of Mexican Music (2016). It’s a comprehensive, informative, and even fun excursion through the entire scope of Mexican music in its historical context, complete with audio and video links.

Una cancion de California, 1848

Oscar E. Berninghaus, The Forty-Niners, 1942, Oil on canvas

We begin with one last look at The Forty-niners by Oscar Berninghaus (see The Other Artists). Mexican inhabitants of California noticed the influx of American gold seekers into their territory after the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), and weren’t especially thrilled. The song “Ahí Vienen Los Yankees” (“There Come the Yankees”) conveys a sense of their complaint in 1848 about their new neighbors (and, no, there is no connection to the New York team):

We begin with one last look at The Forty-niners by Oscar Berninghaus (see The Other Artists). Mexican inhabitants of California noticed the influx of American gold seekers into their territory after the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), and weren’t especially thrilled. The song “Ahí Vienen Los Yankees” (“There Come the Yankees”) conveys a sense of their complaint in 1848 about their new neighbors (and, no, there is no connection to the New York team):

Y a las señoritas que hablan el inglés,

Los Yankees dicen “Kiss me!” y ellas dicen “Yes.”

And to the young ladies who speak English,

The Yankees say “Kiss me!” and they say “Yes.”

(From Harry R. Wilson, Victor C. Neisch. Cantemos!: A Collection of Spanish Songs for Group Singing. The Penny Press Series, NY: Emerson Books, p. 27; no copyright or publication date, but the publisher was active in the 1930s.)

Las canciones de los vaqueros

Frederic Remington | The Sentinel | 1889 | Oil on canvas | 34 x 49 inches

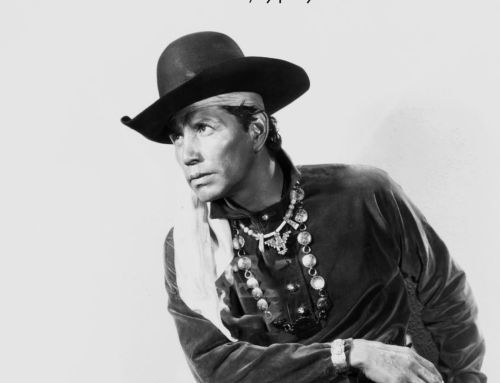

Remington’s painting The Sentinel (1889) depicts a member of the Tohono O’Odham tribe (formerly, “Papago”) on guard duty outside the Mission San Xavier del Bac, south of Tucson, Arizona. Although he is not actually a vaquero, his clothing is similar to that of the nearby Arizona vaqueros: wide sombrero, knotted neckerchief, white clothing, and chaps.

The vaqueros of Mexico and the American southwest were the first cowboys in North America. Early American cowboys learned the tricks of the cattle trade from them, and also adopted – or adapted – much of their clothing and equipment. They also learned the Spanish ranch terminology and organization. For example, the word “buckaroo” is the Americanized version of the word “vaquero”; “lariat” comes from “la reata”, meaning “the rope”. The ranch overseer or boss was the “mayor domo” or “administrador”; the working organization on a ranch was a “corrida” which was led by a “caporal”, similar to an Army first sergeant. Each corrida had a “cocinero” (cook), a “remudero” (horse wrangler), and several vaqueros (Texas folklorist J. Frank Dobie, “The Mexican Vaquero of the Texas Border”, The Southwestern Political and Social Science Quarterly, June 1927, 8(1):15-26.)

“El Charro” is a humorous song with a friendly back-and-forth between a needy vaquero named Nicolás and his very generous ranch boss (“mayor domo”). In the song, the boss repeatedly indulges Nick, at least until he makes a very personal request. This was one of the ranch songs which Charles Lummis collected in southern California in the early 1920s. His friend and colleague Arthur Farwell was a composer and publisher in the Indianist Movement in the early twentieth century who also arranged cowboy songs and other folk songs (see Cowboy Composers). While visiting Lummis in California in 1923, Farwell harmonized the songs that Lummis had collected. Together, they published Spanish Songs of Old California. “El Charro”, or “The Kind-Hearted Boss” (p. 28) is also in The Latin-American Song Book, Ginn and Co., 1942, p. 32-33.

“El Charro” is a humorous song with a friendly back-and-forth between a needy vaquero named Nicolás and his very generous ranch boss (“mayor domo”). In the song, the boss repeatedly indulges Nick, at least until he makes a very personal request. This was one of the ranch songs which Charles Lummis collected in southern California in the early 1920s. His friend and colleague Arthur Farwell was a composer and publisher in the Indianist Movement in the early twentieth century who also arranged cowboy songs and other folk songs (see Cowboy Composers). While visiting Lummis in California in 1923, Farwell harmonized the songs that Lummis had collected. Together, they published Spanish Songs of Old California. “El Charro”, or “The Kind-Hearted Boss” (p. 28) is also in The Latin-American Song Book, Ginn and Co., 1942, p. 32-33.

Like the American cowboy, the vaquero was far from the top of any social ladder. To his northern neighbors, he was a papist peon, and to his more genteel compatriots in central Mexico, he was “el bárbaro del Norte” (or “the northern barbarian”). So the songs of the vaquero, like those of the cowboy, were of little interest to anyone beyond the sound of his voice.

But there were a few enthusiasts, besides Lummis and Farwell, who collected and preserved the songs of the vaqueros, in the same way that John Lomax, Jack Thorp, and just a few others collected American cowboy songs in the early 1900s. Among them were Vicente T. Mendoza (1894-1964) composer, researcher, collector and arranger of Mexican folk songs, and Américo Paredes (1915-1999) a University of Texas professor who began collecting Texas border songs as a teenager.

According to Texas folklorist J. Frank Dobie:

“The love song is by far the most common of all Mexican folk-songs. During the trail driving days many of the cowboys who drove herds from Southern Texas to Kansas and beyond were Mexicans. I have often asked old trail drivers if the vaqueros had any such songs as the Texas cowboys had. Invariably the answer has been that the vaqueros sang little else but love songs (J. Frank Dobie, ed. “Versos of the Texas Vaqueros (With Music)”, Happy Hunting Ground, Publications of the Texas Folklore Society, No. IV, 1925, p. 30-43, specifically p. 41-42.)

“El Abandonado” is one of the melodies that Dobie transcribed. It had already been published in Mexico in 1913, before appearing in Vincent T. Mendoza’s book La Canción Mexicana (1961, 1982, p. 372-3). It also appears in American Ballads and Folk Songs by John A. and Alan Lomax, 1934, p. 364-366. The song is a poor man’s lament after his lover abandoned him.

“El Abandonado” is one of the melodies that Dobie transcribed. It had already been published in Mexico in 1913, before appearing in Vincent T. Mendoza’s book La Canción Mexicana (1961, 1982, p. 372-3). It also appears in American Ballads and Folk Songs by John A. and Alan Lomax, 1934, p. 364-366. The song is a poor man’s lament after his lover abandoned him.

Mendoza transcribed several other ranch songs. “La Rancherita” is a song from San Luis Potosi in about 1895, which expresses a longing for a poor little ranch girl (La Canción Mexicana, p. 185.) “El Caballito” (“The Little Horse”) is a conversation between two vaqueros (from song No. 58 in Mendoza, Canciones Mexicanas, 1948, p. 124-6.)

Mendoza transcribed several other ranch songs. “La Rancherita” is a song from San Luis Potosi in about 1895, which expresses a longing for a poor little ranch girl (La Canción Mexicana, p. 185.) “El Caballito” (“The Little Horse”) is a conversation between two vaqueros (from song No. 58 in Mendoza, Canciones Mexicanas, 1948, p. 124-6.)

The term “corrido,” in addition to being a ranch term, is also the name for a type of Mexican ballad or folksong. In her Master’s Thesis, Carlos Chávez and the Corrido (Bowling Green State U., Ohio, Dec. 2005., p. 8), Amber Waseen describes a corrido as follows:

The hallmark of the corrido is flexibility, which has contributed to its survival. Principal characteristics include the division of text into quatrains (cuartetas) made up of octosyllabic lines with consonantal rhyme in a narrative design.” … “Indeed, the message of the corrido is more important than its adherence to a definitive form.

“Kiansis” is a corrido or ballad, about a cattle drive, from the Mexican point of view. Américo Paredes provides two variants of the song in his book A Texas-Mexican Cancionero: Folksongs of the Lower Border (1976, p. 53-55), in which he describes the song and how it was passed down in his family (p. 25-26):

“Kiansis” is a corrido or ballad, about a cattle drive, from the Mexican point of view. Américo Paredes provides two variants of the song in his book A Texas-Mexican Cancionero: Folksongs of the Lower Border (1976, p. 53-55), in which he describes the song and how it was passed down in his family (p. 25-26):

The cattle drives to Kansas furnished the subject for the oldest complete corridos from the Lower Rio Grande Border – among the oldest in Greater Mexican tradition… “El corrido de Kiansis” exists in several variants and is the oldest Texas-Mexican corrido that we have in complete form… [It] has been sung in my family (and in other Border families as well) since the 1860s. I first learned a complete version from one of my granduncles, Hilario Cisneros, born in 1867, who learned it from the vaqueros who had made the first trips on the trail to Kansas.

There is intercultural conflict in “Kiansis,” but it is expressed in professional rivalries rather than in violence between men. Death lurks on the horns of a wild bull or in the deep currents of a stream, rather than in the muzzle of a forty-four. Anglo accounts of the cattle drives, however, mention incidents of Mexican vaqueros shot out of hand by Anglo trail bosses because the Mexicans misunderstood orders, and of Mexican outfits attacked by Anglos while on the trail in competition for water and grazing space. The “Kiansis” corridos make no mention of such incidents, perhaps because armed conflicts between Mexicans and Anglos were part of another kind of situation, already quite familiar to the Mexican, while the cattle drives to the North were something new and exciting.

Arriba en la pantalla grande

(Up on the Big Screen)

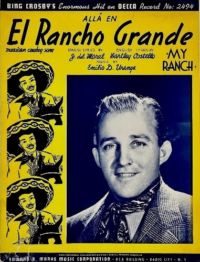

“Allá en el Rancho Grande” (“Down on the Big Ranch”, Latin-American Song Book, 1942, p. 102-4; attributed to Silvano Ramos, 1927) was originally composed for a musical play in Mexico in the 1920s. After being forgotten for a several years, it was copyrighted in the U. S. by 1934, then resurrected in Mexico in 1936 and featured in a movie by the same name. The song became a huge hit in Mexico, launching the on-screen careers of singers Tito Guízar and Jorge Negrete. The phenomenon was mirrored north of the border by the popular singing cowboys of the silver screen. Several other singers also recorded the song, including Bing Crosby in 1939.

Corridos de las Contrabandistas

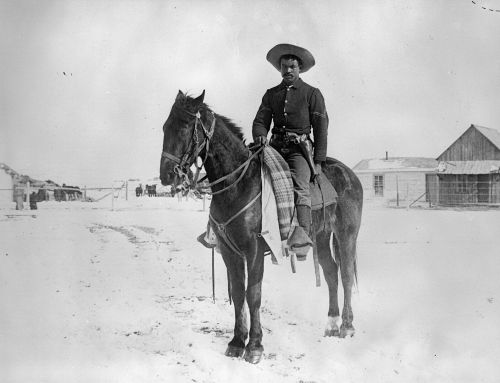

Frank Tenney Johnson, Contrabandista a la Frontera, 1925, Oil on canvas, 36 1/8 x 45 1/8 inches

Contrabandista a la Frontera is one of two Frank Tenney Johnson paintings at the Sid Richardson Museum (see The Symphony of the Other Artists for information on his painting Trouble on the Pony Express). I read the painting as depicting an unexpected interruption in a nighttime smuggling operation at the border, with the smugglers’ pack mules halted, and their guns drawn. Given the date of the painting (1925) – in the middle of Prohibition – could those mules be carrying bottles of liquor? Two border corridos are appropriate for this painting, and helped set the stage for the later development of the modern “narcocorrido” genre.

”El Contrabando de El Paso” (Paredes, A Texas-Mexican Cancionero, Song No. 37, p. 103-105) is the ballad of a remorseful border smuggler from the era of Prohibition (1920–1933) who ended up at Leavenworth Prison (“Lerinbor”). Probably the most famous version of the song is by Los Alegres de Teran.

“Corrido de Cananea” or “The Ballad of the Cananea Jail” is the story of a prisoner in the jail at Cananea, Sonora; it was written after a mining strike there in 1917. There are many variations and recordings of this song, including one by Linda Ronstadt on her 1987 LP, Canciones de Mi Padre.

Corridos and Composers

In the same way that Native American music and cowboy songs have been used in American classical music, a few Mexican composers have looked to traditional corridos for inspiration. Among them are Carlos Chávez (1899-1978, see Amber Waseen’s Master’s Thesis Carlos Chávez and the Corrido mentioned above), Manuel Ponce (1882-1948), and Candelario Huízar (1883-1970). Contemporary examples (provided by Dr. Janet Sturman) are William Owens (“El Vaquero!” for concert band), and the opera “Quatro Corridos”:

Cuatro Corridos is a chamber opera addressing one of the most critical human rights issues of our time: human trafficking. Based on true events, it tells the story of women trapped in a cycle of prostitution and slavery in and around the San Diego/Tijuana border region. Cuatro Corridos represents an unprecedented collaboration between internationally acclaimed Mexican and US-based creative artists. (Cuatro Corridos – History and Mission, http://cuatrocorridos.com/the-opera )

Coda: Compose Your Own Corrido

If you now feel inspired to create your very own corrido, you may want to look at the Library of Congress lesson on composing Corridos. Please consider posting your composition here if you write or record one.

Leave A Comment