*The following is part of a series of blog posts researched and written by Mark Clardy, SRM Docent and independent scholar.*

Soundtrack of the American West

The Artist’s Playlists

Frederic S. Remington’s Playlist

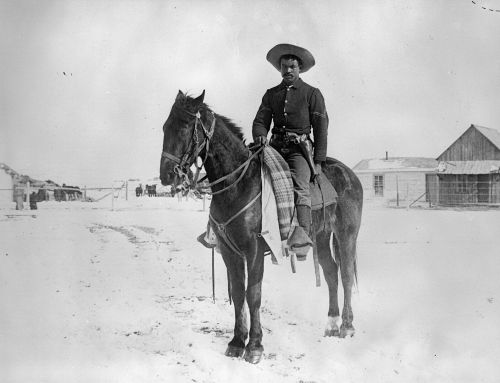

Self-Portrait On A Horse | Frederic Remington | c. 1890 | Oil on canvas | 29.1875 x 19.375 inches

Frederic S. Remington, At Work

Remington stayed up-to-date with currently popular music; after all, his home wasn’t far from New York City and Tin Pan Alley. So for him, painting was not a silent activity, and visitors to his studio commented on his vocal accompaniment while he painted. Mary Burke, former Director of the SRM, brought the following quote to my attention:

He could concentrate under any circumstance. When he painted on vacation, the people near him said they ‘thought we would go mad’ while ‘he’d sit cross-legged painting, diddling his free foot up and down, up and down, and whistling, whistling, whistling’…

In Taos, New Mexico he told European-trained Bert Phillips how to add dash to a picture. He hummed fast popular music and painted in timed strokes. Tum tiddy tum tum was stroke dab dab stroke stroke.” (Harold Samuels, Peggy Samuels, Joan Samuels, & Daniel Fabian, Techniques of the Artists of the American West. 1992, p. 176, 177.)

John Ermine’s Singing Lieutenant

“Billy Barlow” image, courtesy Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection, The Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University

“Billy Barlow” was published by George Endicott in 1836, and was billed as “a comic ballad, as sung by JACK REEVE, with UNBOUNDED APPLAUSE.” There are many songs in the British and Australian traditions about a ragged scamp called Billy Barlow. This American version was published in New York in 1836 (from the Lester S. Levy sheet music collection, Johns Hopkins University). Later versions circulated during the Civil War and afterwards in minstrel shows. Although it is described as a comic minstrel song, there is an undeniable pathos lying beneath the lyrics which is supported by the music. In modern terms, we might say that the song describes how the homeless population survived in the Victorian Era and the Gilded Age.

The tune is quite catchy. At least, Frederic Remington appears to have thought so. He has Lieutenant Shockley sing the song in his book John Ermine of the Yellowstone (1902, p. 181):

“There is no champagne like the air of the high plains before the sun burns the bubble out of it,” proclaimed Shockley, who was young and without any of the saddle or collar marks of life; “and to see these beautiful women riding along – say, Harding, if I get off this horse I’ll set this prairie on fire,” and he burst into an old song: –

“Now, ladies, good-by to each kind, gentle soul,

Though me coat it is ragged, me heart it is whole;

There’s one sitting yonder I think wants a beau,

Let her come to the arms of young Billy Barlow.”

There is no indication that the song was included in the 1903 Broadway production of John Ermine. His lyrics, above, differ slightly from the actual 1836 verse:

O dear but I’m tired of this kind of life.

I wish in my soul I could find a good wife;

If there’s any young Lady here, in want of a beau,

Let her fly to the arms of sweet Billy Barlow.

O dear raggedy O, Let her fly to the arms of sweet Billy Barlow.

Comin’ Thro’ a Craze

Coming Through the Rye | Frederic Remington (1861-1909) | Copyrighted October 8, 1902 | Roman Bronze Works cast #1, 1902 | Private Collection

“Comin’ Thro’ the Rye” is a traditional Scottish song written by (or attributed to) Robert Burns in 1782. Its overtly sensual lyrics about a wet girl walking in a field of rye are set to the Scottish melody “Comin’ Frae the Town”. The arrangement here by William Dressler is from 1851.

“Comin’ Thro’ the Rye” is a traditional Scottish song written by (or attributed to) Robert Burns in 1782. Its overtly sensual lyrics about a wet girl walking in a field of rye are set to the Scottish melody “Comin’ Frae the Town”. The arrangement here by William Dressler is from 1851.

The phrase “comin’ thro’ the rye” enjoyed a “wink-wink, nudge-nudge” kind of popularity through the 1800s and into the twentieth century (Monty Python, anyone? Say no more.) It became a meme, a Victorian metaphor for a plein air tryst, a lovers’ rendezvous with a ‘steam’ setting somewhere between sentimentally romantic and erotic.

The phrase popped up everywhere: in literature, art, music, and stage – always with the romantic/erotic connotation. Ellen Buckingham Mathews (1853–1920, pen name: Helen B. Mathers) wrote a novel by the same name in 1875 based on her personal romantic experiences, with several subsequent editions. Daniel Ridgway Knight, an artist whose paintings are almost entirely of young farm women in the countryside, used the name for a painting in the mid-1890s. George Boughton and Jerome Thompson were also prominent American painters in the mid-1800s with paintings named “Comin’ Thro’ the Rye”. (Clara Erskine Clement Waters, Artists of the Nineteenth Century and Their Works, 1884.)

Several musical plays titled “Comin’ Thro’ the Rye” were produced on Broadway in the early 1900s. The earliest was in 1901 with the song “I Think It Must Be Love”. George V. Hobart had 34 performances of his “Comin’ Thro’ the Rye” in 1906 at the Herald Square Theater on Broadway; one of the songs was “I Love You Because You Are You”. Hobart sued Will J. Block for infringement for his 1906 production starring Stella Mayhew at Garrick Theatre in Chicago (example songs: “You’re An Indian”, “I Guess I’ll Take the Train Back Home”, “I Know a Girl Like You”). The next year, the Rorke Co. play featured Sallie Stembler (example song: “Any Time, Any Place, Any Way”).

Tin Pan Alley cashed in on the phrase, as well. Harry Von Tilzer published his “most beautiful ballad” in 1902, a sentimental song titled “When Kate and I were Coming Thro’ the Rye”, in keeping with the lovers-in-a-field theme.

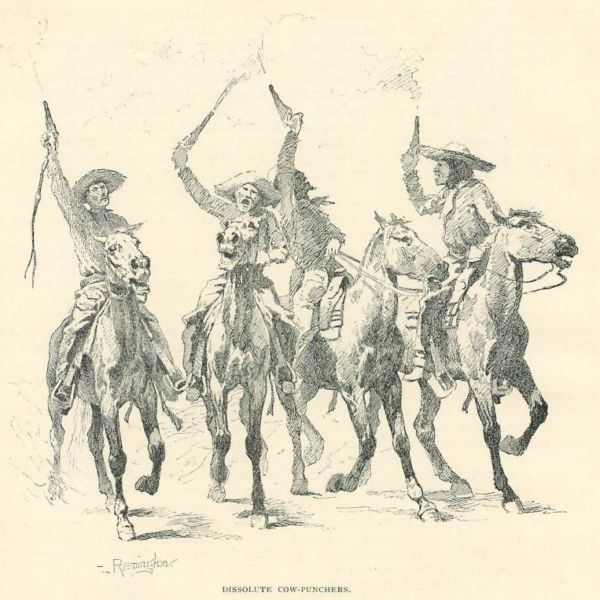

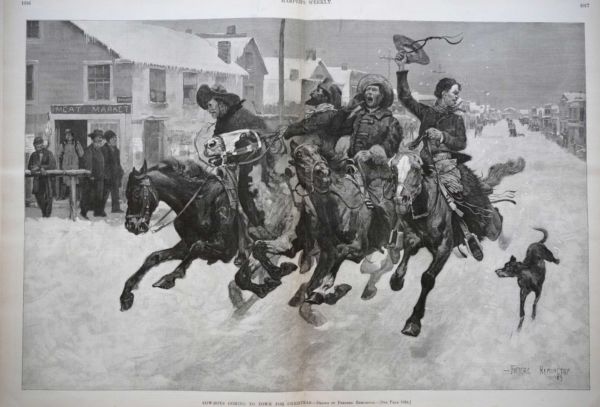

This may have caused an overload of romantic sentimentality for Remington in 1902, so it was time for something completely different. He had two earlier illustrations of cowboys on horseback rampaging through town, pistols blazing. One was called “Dissolute Cow-Punchers” (Century Magazine, October 1888, 36(6):836) and the other, “Cow-boys Coming to Town for Christmas” (Harper’s Weekly, December 1889, 33(1722):1016-1017). Inspired by these raucous images, he designed a new sculpture of carousing cow punchers. By November 1902, he had settled on the intentionally ironic name Comin’ Thro’ the Rye. Remington’s new sculpture could have been his answer to the romantic nonsense symbolized by its name. It was perfect.

Frederic Remington, “Dissolute Cow-Punchers” (Century Magazine, October 1888, 36(6):836)

“Cow-Boys Coming to Town for Christmas” | Frederic Remington (1861-1909) | 1889 | Wood Block and Magazine Print | Sid Richardson Museum | 2001.1.1.139

Remington did have some push-back, however. On February 2, 1905, A. F. McGuire, the Director of the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, wrote to Remington about their recently acquired piece: “I think the title ‘Off the Range’ is much more appropriate for the work than ‘Coming through the Rye,’…” (From Allen P. Splete and Marilyn D. Splete, Frederic Remington: Selected Letters, 1988, p. 354.)

A Musical ‘Encounter’ in New Rochelle

In the 1890s, Frederic and Eva Remington had their home and studio in the swanky Huguenot Park subdivision of New Rochelle, a suburb north of New York. Their neighbors were prominent businessmen and creative sorts such as playwrights and actors. One neighbor in particular stands out for his impact on Frederic: the composer George L. Spaulding (1864–1921). Spaulding made a good living cranking out a stream of simple piano pieces for beginning students with titles such as “Sing, Robin”, “Sing, Pretty Little Song Bird”, “Airy Fairies”, etc. He also wrote ‘Indian Characteristic’ pieces during the Indianist era, such as “Osceola” (1904). “Two Little Girls in Blue” was written by Charles Graham and published in 1891; but after his song became a hit, Spaulding and Korander republished it and added Spaulding’s name as a co-writer. In fact, Remington thought that Spaulding had composed this sad little song.

In the 1890s, Frederic and Eva Remington had their home and studio in the swanky Huguenot Park subdivision of New Rochelle, a suburb north of New York. Their neighbors were prominent businessmen and creative sorts such as playwrights and actors. One neighbor in particular stands out for his impact on Frederic: the composer George L. Spaulding (1864–1921). Spaulding made a good living cranking out a stream of simple piano pieces for beginning students with titles such as “Sing, Robin”, “Sing, Pretty Little Song Bird”, “Airy Fairies”, etc. He also wrote ‘Indian Characteristic’ pieces during the Indianist era, such as “Osceola” (1904). “Two Little Girls in Blue” was written by Charles Graham and published in 1891; but after his song became a hit, Spaulding and Korander republished it and added Spaulding’s name as a co-writer. In fact, Remington thought that Spaulding had composed this sad little song.

One fine Spring day in 1895, while on his way to the train station, George Spaulding ran into Frederic Remington. Actually, it was more of a crash.

March 23, 1895, New York Times

FREDERIC REMINGTON WINS

AWARDED $45 FOR BEING RUN INTO BY MR. SPAULDING.

Against This, However, are the Loss of His Buckboard’s Wheel and a Shock to His Brindle Pup.

NEW-ROCHELLE, N. Y., March 22.- Justice Swinburne to-day rendered a decision in favor of Frederic Remington, the artist, in his suit for $45 damages against George L. Spaulding, the song writer. Mr. Spaulding’s carriage and Mr. Remington’s buckboard met forcibly on Feb. 23.

This important decision, by which Mr. Remington is in an instant, as it were, made $45 richer, was in a measure anticipated by New-Rochellites. They failed to see how it could be otherwise.

Mr. Remington, early on the morning of Feb. 23, was being driven up Luther’s Hill by his coachman. He held a brindle pup in his lap, and was congratulating himself that so few artists could draw real cowboys. All was serene. Mr. Spaulding’s coach was being rather hurriedly driven down hill by a coachman, for, like a true suburbanite, Mr. Spaulding had figured to a nicety just how long it would take him to drive from his house to the station to catch the 8:57 train.

There was a crash. Mr. Remington, coachman, and brindle pup were dumped into the mud, and Mr. Remington tried to think of a prayer that he had learned in boyhood’s happy days, before wash drawings were popular. Mr. Spaulding never lost his composure. He said to his coachman: “James, remember, the train leaves at 8:57, and it is never late.”

When Mr. Remington reached home, he looked over the field mentally. His buckboard was minus one wheel. His new Spring suit was ruined. The driver’s high hat, which had just been put in shape against St. Patrick’s Day, was disfigured for life. The brindle pup was suffering from shock.

As Mr. Spaulding did not call around and offer to settle, Mr. Remington thought that he ought to pay in full the damages, which an expert had estimated at $45. There was a conversation between Mr. Remington and Mr. Spaulding, and a lawsuit. It is not known whether Mr. Spaulding will appeal.

Remington’s $45 win would be equivalent to about $1500 in today’s inflated money. After the accident, Remington wrote to Poultney Bigelow about his unfortunate encounter with Mr. Spaulding (Frederic Remington: Selected Letters, p. 269):

I won the law suit – we smothered the defense – a damned song writer does “Two Little Girls in Blue” – gets rich – buys a damn plug – thinks he owns the roads – runs into the wrong man – gets it in the neck for $150. – no moral.

It is unknown whether Remington had any appreciation for the remainder of Mr. Spauldings’ musical output (or how his court award increased to $150.)

Hot, Hot, Hot!

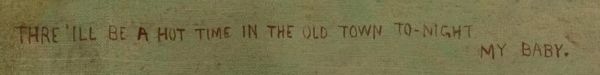

“A Hot Time in the Old Town” (1896) became the theme song for Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, and was a favorite among the American troops during the Spanish-American War. Remington’s painting Thre’ill Be A Hot Time in the Old Town To-Night My Baby depicts one of the Rough Riders, and includes that misspelled inscription/title at the top of the painting. It sold at Sotheby’s in New York on May 21, 2009 for $89,500.

“A Hot Time in the Old Town” (1896) became the theme song for Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, and was a favorite among the American troops during the Spanish-American War. Remington’s painting Thre’ill Be A Hot Time in the Old Town To-Night My Baby depicts one of the Rough Riders, and includes that misspelled inscription/title at the top of the painting. It sold at Sotheby’s in New York on May 21, 2009 for $89,500.

Inscription on painting

Last Thoughts

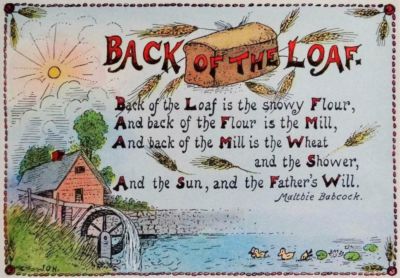

“Back of the Loaf” is a short poem by Maltbie Davenport Babcock (1858–1901; she also composed “This Is My Father’s World”.) Her poem traces backward in time the steps that result in a loaf of bread:

Back of the loaf is the snowy flour,

And back of the flour the mill,

And back of the mill is the wheat and the shower

And the sun and the Father’s will.

At the beginning of what would be the last year of his life, Remington inserted a newspaper clipping of this poem into his diary beneath his entry for Sunday, January 24, 1909. The poem’s sentiment clearly struck a chord with him. By 1909, Grant Colfax Tullar (1869–1950) had set the popular little poem to music. The song was featured in flour advertisements and postcards, and was also included in later hymnals and Sunday School songbooks.

And so ends our visit in the artists’ studios, hearing the music that they heard. Next, we’ll hear music from some of the other artists in the Sid Richardson collection.

[…] Frederic S. Remington’s Playlist […]