*The following is part of a series of blog posts researched and written by Mark Clardy, SRM Docent and independent scholar.*

Symphony of Native America

Movement 4

The Southwest

Apache Medicine Song & Geronimo

Frederic Remington wrote about his trip to the San Carlos Apache Reservation in southeast Arizona in “On the Indian Reservations,” for the July 1889 issue of Century Magazine (Vol 38, p. 399-400). In the article, he appears to describe the scene in Apache Medicine Song:

“It grew dark, and we forbore to talk. Presently, as though to complete the strangeness of the situation, the measured ‘thump, thump, thump’ of the tom-tom came from the vicinity of a fire some short distance away. One wild voice raised itself in strange discordant sounds, dropped low, and then rose again, swelling into shrill yelps, in which others joined. We listened, and the wild sounds to our accustomed ears became almost tuneful and harmonious. We drew nearer, and by the little flickering light of the fire discerned half-naked forms huddled with uplifted faces in a small circle around the tom-tom. The fire cut queer lights on their rugged outlines, the waves of sound rose and fell, and the ‘thump, thump, thump’ of the tom-tom kept a binding time. We grew in sympathy with the strange concert, and sat down some distance off and listened for hours. It was more enjoyable in its way than any trained chorus I have ever heard.”

Apache Medicine Song | Frederic Remington | 1908 | Oil on canvas | 27.125 x 29.875 inches

“Geronimo – Two Step,” 1905

Geronimo – Sep1905 Indian School Journal, v5n9p8

The Apache leader Geronimo held a certain fascination among the American public because of his role in the Apache wars, 1849-1924. Often referred to as an Apache Chief, his position in the tribe is more accurately described as a Holy Man, or Medicine-man. After his surrender in 1886, he became a celebrity and even toured the country in the early 1900s, so it is only natural that there would be a popular song named after him: “Geronimo – Two Step” (1905). (Nevermind that the cover show a Plains Indian wearing a feathered war bonnet in an evergreen forest near teepees on the edge of a lake.)

There are, however, actual songs that Geronimo sang. While whittling an arrow for tourists at the St. Louis Exposition in 1906, he hummed a song to himself which Frances Densmore (surreptitiously) transcribed and published as “Geronimo’s Song” (April 1906, The Indian School Journal, The U. S. Indian Service: U. S. Indian School, Chilocco, Oklahoma, p. 30-31.) The following year, Natalie Curtis published “Geronimo’s Medicine Song” in her collection of Native American music, The Indians’ Book (1907). She quoted his own description of the song:

Geronimo, 1917, Carlos Troyer

“The song that I will sing is an old song, so old that none knows who made it. It has been handed down through generations and was taught to me when I was but a little lad. It is now my song. It belongs to me… This is a holy song (medicine-song), and great is its power. The song tells how, as I sing, I go through the air to a holy place where Yusun [the Supreme Being] will give me power to do wonderful things. I am surrounded by little clouds, and as I go through the air I change, becoming spirit only.”

Being an old song, could Geronimo’s “Medicine Song” have been on the play list in Remington’s painting?

Indianist composer Carlos Troyer adapted Curtis’ transcription of Geronimo’s song in 1917 as “Geronimo’s Own Medicine Song”, adding a drum-like left hand accompaniment, but leaving the melody intact. Troyer heard the song sung by Chief “Eagle Eye” who had learned the song from Geronimo, and provided additional details. The sheet music cover features a swastika, “Symbolic emblem of the Sun worshippers”, a drawing of a plains teepee captioned “Apache Wigwam,” and a photograph by C. S. Fly, provided by Charles F. Lummis captioned, “GERONIMO in 1886, on the Warpath.”

The Tohono O’Odham (The Papago Tribe)

The Sentinel

The peaceful Tohono O’odham people (formerly known as Papago) were very watchful of their more warlike traditional enemies, the Apaches. Posting sentinels was a common practice, as seen in Remington’s painting The Sentinel (1889). In her book Papago Music (BAE Bulletin #90, 1929), Frances Densmore transcribed one of their songs which taunted their Apache enemies “The Apache Hid Behind Trees” (Song No. 128, p. 178). The original Tohono O’odham text was not provided. Instead, Densmore provided the following text to explain the intended meaning, which was probably conveyed by just a few words:

Yonder, near the enemy’s country, stand many great trees behind which they hid.

They have retreated farther. They act like children.

They hide behind the women or anything that will conceal them.

The Sentinel | Frederic Remington | 1889 | Oil on canvas | 34 x 49 inches

The Luckless Hunter

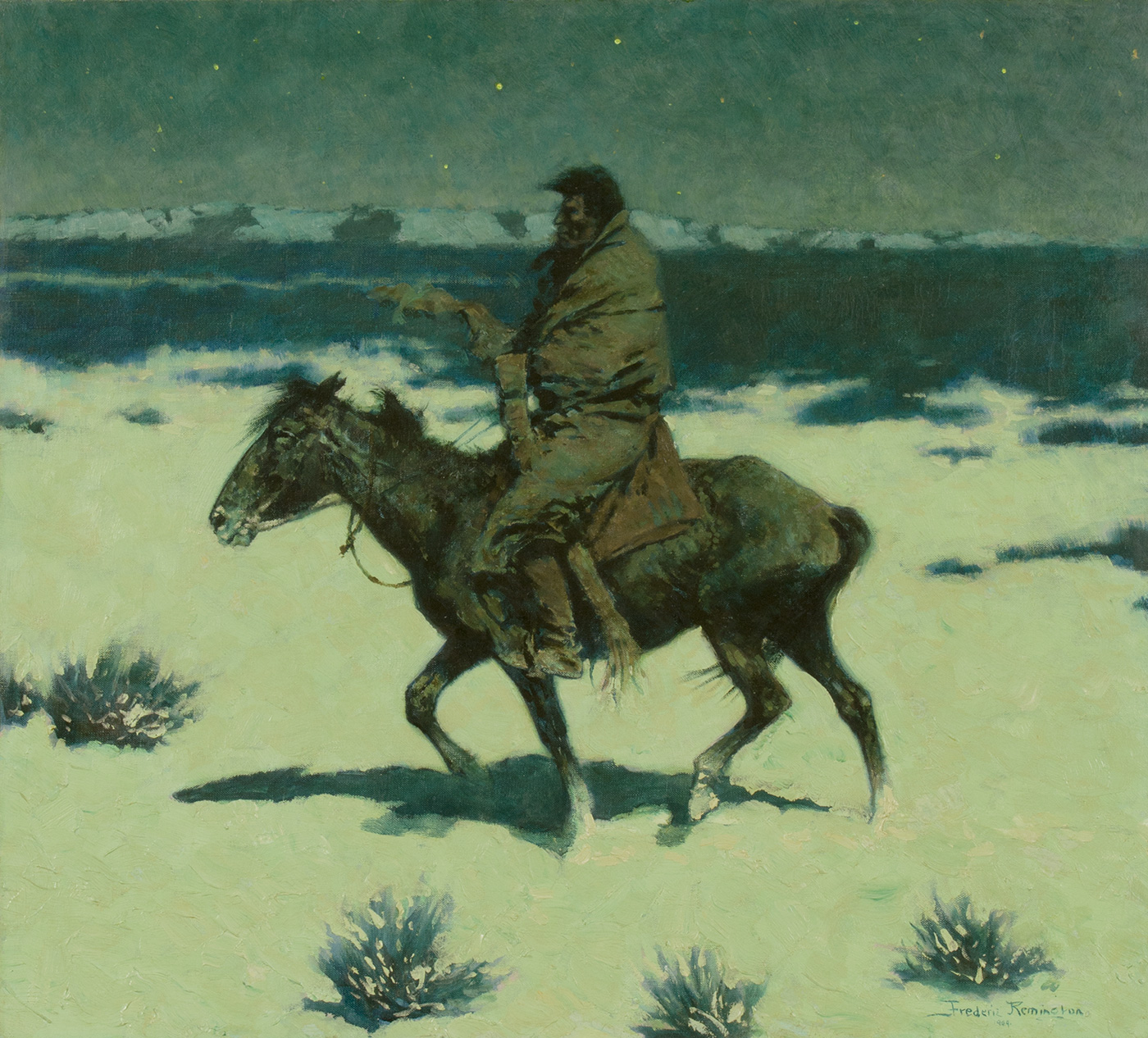

Frederic Remington painted this cold, bleak scene shortly before his death in 1909. Although the figure in the painting is not identified by tribe, there is a Tohono O’Odham song that perfectly matches his situation. Frances Densmore, transcribed the “Song of an Unsuccessful Hunter” (Song No. 161, p. 211), as sung by Jose Manuel. The lyrics were translated as: “I am walking a great deal. I am sorry I cannot find any game. I saw lots of tracks, especially on the east side of the mountain, but I found nothing.”

The Luckless Hunter | Frederic Remington | 1909 | Oil on canvas | 26.875 x 28.875 inches

Nai-U-Chi & Zuni Melodies

Portrait of Nai-Uchi (Elder Brother of the Bow Priest) in Native Dress with Squash Blossom Necklace and Ornaments 1879. Photographed by John K. Hillers. National Anthropological Archives. NAA INV 06370200 OPPS NEG 02233 A.

Every academic enterprise has stories about a race to publish, and musicology is no exception. Alice Fletcher became interested in the music of the Omaha after she began working among them in 1883 as a government agent for land allotments, with Francis La Flesche first as her interpreter, and later as her research partner. Over the years, they had accumulated a large collection of Omaha music which Fletcher planned to publish in the early 1890s for her debut as a serious researcher in the field. Then in the spring of 1891, she heard about the well-funded Hemenway Archæological Expedition to the Zuñi Pueblo in New Mexico. It started in 1886, and had just acquired a graphophone (i.e., phonograph) for music research. The race to publish was on.

In the summer of 1890, Dr. J. Walter Fewkes replaced Frank Hamilton Cushing to lead the expedition, and brought a treadle-operated graphophone with him to Zuñi. Several Zuñi singers sang into the contraption to record ten wax cylinders, which Benjamin Ives Gilman later transcribed and analyzed. This is the first known instance of music transcriptions being made from wax cylinder recordings, rather than from a live performer.

Nai-U-Chi emblem, “Aboriginal Pilgrimage,” p526

Gilman won the race to publish; his report appeared in 1891 in the first volume of Fewkes’ Journal of American Ethnology and Archæology. Among the transcribed songs were “Sacred Dance of the Ko-Ko” (III) and “Kor-Kok-Shi” (VIII). Alice Fletcher’s A Study of Omaha Indian Music appeared in 1893. With 92 songs, it was the largest collection of music ever published from a single tribe, and had a significant, maybe even overbearing, influence on Indianist composers who made extensive use of her materials.

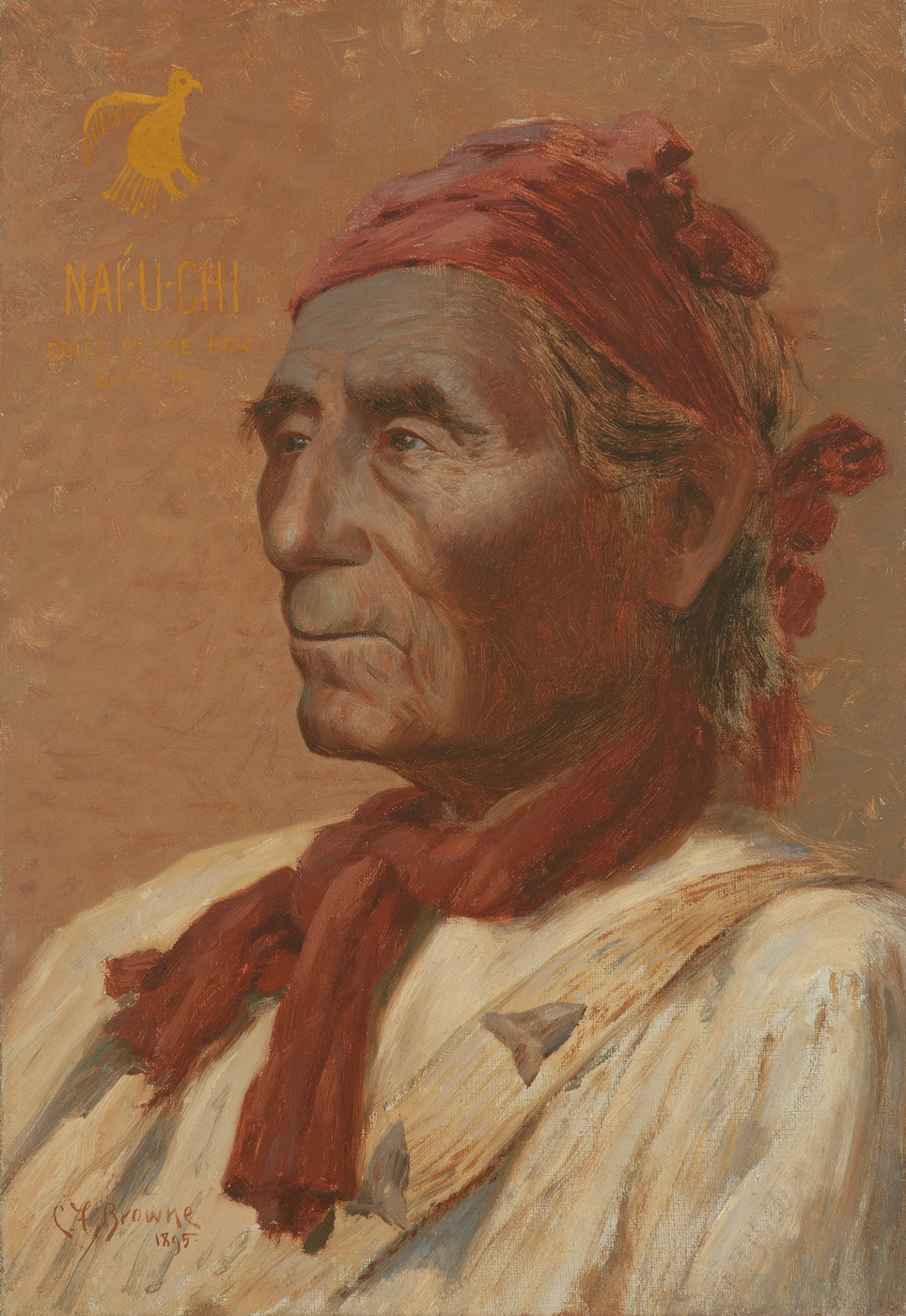

A few years later, Charles Francis Browne arrived at Zuñi with two other artist friends in the summer of 1895. His portrait Nai-U-Chi: Chief of the Bow, Zuni 1895 is similar to a younger “Portrait and Autograph of Nai-Iu-Tchi, Senior Priest, Order of the Bow, Clan of the Eagles, Sun and Rattlesnake, Emblems of His Orders” from an article about Zuñi leaders (including Nai-U-Chi) who traveled by train with Frank Cushing to Washington, D. C. in 1882 (Sylvester Baxter, “An Aboriginal Pilgrimage”, Century Magazine, Vol. XXIV, No. 4, Aug., 1882, p. 526-536.)

Nai-U-Chi: Chief Of The Bow, Zuni 1895 | Charles Francis Browne | 1895 | Oil on canvas | 18.5 x 12.75 inches

Zuni – Traditional Songs – Carlos Troyer

Zuni Impressions – Homer Grunn

Indianist composers Carlos Troyer and Homer Grunn wrote compositions based upon Zuñi music, but it appears that they made their own observations and transcriptions at Zuñi instead of making use of Gilman’s transcriptions. Troyer wrote several pieces in his series Traditional Songs of the Zuni Indians, including “The Great Rain-dance of the Zunis” and “Zuñian (“Kor-kok-shi”) Clown Dance” in 1904. Grunn published his Zuñi Impressions, Op. 27, in 1917, but of the four pieces, “Kor’kokshi Dance (Rain Ceremony)” was the only one based upon Zuñi sources.

There is much more that we could hear in our Symphony of Native America, but there are other voices clamoring to be heard in our ongoing series, The Soundtrack of the American West. Next up: Cowboy Songs.

Leave A Comment