*The following is part of a series of blog posts researched and written by Mark Clardy, SRM Docent and independent scholar.*

A Cowboy Chorale

From the wildflower covered plains of south Texas, the sounds and songs of the cattle trails stampeded out of the sunset, into the Soundtrack of the American West. In the years after the Civil War, the nation, both North and South, was exhausted – and hungry. Eastern farms and ranches that had been ravaged or raided during the war years, couldn’t provide enough cattle to satisfy the craving for beef. But in Texas… Ahh, the cattle there had been left untended and undisturbed, “doin’ what comes naturally.”

The question, then, was this: How could an entrepreneurial person move those prolific, plentiful, and cheap cattle from their home on the Texas range, to the eager paying customers in the expensive restaurants of New York? Since the nearest railroads to south Texas were a thousand miles to the north in Kansas, someone would have to round up the cattle in the spring, brand them, then coax them northward over the next several months to the railheads in Kansas.

That someone was the American cowboy.

But who, exactly, was he? First of all, he never referred to himself as a “cowboy”; his term for himself was “puncher.” (However, we’ll use the more familiar term here.) To many who had successfully climbed the social ladder, the cowboy was below the lowest rung, with few, if any, redeeming qualities. The following assessment is from a writer in Kansas in 1872:

“From Steer to Steak” by A. W. Lyman, Kansas Magazine, April 1872, 1(4):317-323 (quote from p. 321):

The herder is a character. He is be-gotten of a necessity, as was the army bummer. He is sent to fulfill a mission; and that mission is “herdin’ steers,” no one who has ever seen him can for a moment doubt. His pedigree is as much a matter of doubt as that of his steers…

Our first acquaintance with him is in the prime of manhood, when he presents himself to us a full-fledged herder. He is usually tall, muscular, active, and but for shockingly bowed legs, from his constant seat in the saddle, well built; hair long and unkempt and sun-faded; in dress, generally indifferent to color and texture, a pair of jean pantaloons thrust into high-topped boots, a woolen shirt, a belt containing a small arsenal of pistols and cutlery, a slouch felt hat of great width of brim, often a genuine Mexican sombrero. A part of himself might be reckoned his horse, from which he is almost inseparable.

In morals the herder is not a model young man for the Sunday school books. He possesses all the vices that his limited education permits, and if he omits any it is not his fault. As a profane swearer he has few equals, as a gambler he is not surpassed, and as a consumer of mean whisky he is without a peer. Prodigal of his money, heedless of the future, he lives for the day only, and his brief life is usually brought up with a sharp turn by a pistol-shot in a drunken brawl.

His vices are counterbalanced by some virtues. Generous and open-hearted, he will spend his last dollar for his friends, or risk his life in defense of a comrade in danger. Living his whole life without the pale of civilized society, associated with vile men and viler women, it is only a wonder that he is no worse than he is.

But the sin-stained blood and grit of the West disappeared by the early 1900s in the baptismal river of romance and nostalgia. A grateful nation in need of heroes bestowed the mantle of virtuous manhood upon the lowly cowboy, and washed his sins away. He was now honorable, chivalrous, and pure – and worthy of song.

The music of our “Cowboy Chorale” starts with songs that cowboys sang out on the trail. Some of these songs also caught the attention of later arrangers and serious composers. By the early 1900s, there were the songs about the cowboys. In fact, New York’s Tin Pan Alley songsters released a horde of popular songs about the West, even though most of them had probably never been west of New Jersey. Their vast herd of sheet music kept parlor pianos and performers across the country ringing with songs about cowboys and cowgirls. Among them were ballads and comic songs, even ragtime and blues. The Wild West was also a popular topic for novels and their musical stage adaptations. Since movie sound technology had not yet been developed, movie theater pit orchestras played soundtrack music to accompany the action on the screen.

Yes, the panorama of cowboy songs can be as colorful as a Western sunset, and simple as a wind dancing daisy.

Overture to the Cowboy Chorale

For our prelude to the “Cowboy Chorale”, let’s drop in on a dance at the Niedringhaus ranch headquarters in Montana. Brothers Frederick William “Fritz” Niedringhaus (1832-1913) and Frederick Gottlieb Niedringhaus (1837-1922) established their N-N ranch in 1886 in White Deer, Carson County, Texas, northeast of Amarillo. The brand is read “N Bar N”. Beginning in 1892, they moved their herd from Texas to their ranch in Montana where Charlie Russell occasionally worked for them. (For more on the Niedringhaus brothers and Charlie Russell’s connection to the N-N Ranch, see SRM Blog, “Trouble on the Range”, April 15, 2014.)

When Cowboys Get in Trouble (The Mad Cow) | Charles M. Russell | 1899 | Oil on canvas | 24 x 36 inches

Look closely at Russell’s painting When Cowboys Get in Trouble (1899), and you’ll see the Niedringhaus “N-N” branded on the side of the misbehaving cow. Being resourceful cowboys, they most likely survived this hair – and hat – raising incident. If they were on the Montana ranch and not out on the trail, maybe these cowboys returned to the ranch headquarters after retrieving the lost hat. Maybe they even celebrated. After all, cowboys and ranch hands did enjoy their dances and soirees. All they needed was a good floor for stompin’, a fiddler – maybe a guitar or harmonica, and a few local gals. A dance could break out at, well… at the drop of a rescued hat. In about 1886, a waltz tune that was very popular around the N Bar N ranch was appropriately called “The N Bar N Walz”. Maybe these cowboys had been just a bit too distracted while humming it, thinking about their dance partners?

Movement 1 – Songs of the Cattle Drive

“Cowboy Songs: and Other Frontier Ballads” by John A. Lomax, 1910

The songs that the cowboys sang were apparently of little interest to musicologists and anthropologists. Instead, it mostly fell to the cowboys themselves to pass their songs on to others. The first collection, Songs of the Cowboys by N. Howard “Jack” Thorp (1908), contained the lyrics for 24 songs; the 1921 edition contained 104 songs. Thorp also wrote several of the songs, but neither edition provided music. Other collections of cowboy lyrics were: Frontier Ballads by Joseph Mills Hanson (1910), Buckaroo Ballads by S. Omar Barker (1928), Cowboy Lore by Jules Verne Allen, aka “The Singing Cowboy,” Singing Rawhide: A Book of Western Ballads by Harold Hersey (1923), and Songs of the Sage by Curley W. Fletcher (1931).

The first collection to provide music was Cowboy Songs: and Other Frontier Ballads by folklorist and musicologist John Avery Lomax, first published in 1910. The 1916 edition contained 153 songs, 18 of them with music (the 1921 edition removed the music). Four of these songs will be featured in this opening movement of the “Cowboy Chorale: Songs of the Cattle Drive”, and are paired with paintings by Charles Russell. A fifth song, “The Old Chisholm Trail”, is paired with Frederic Remington’s self-portrait for a surprise “Coda” at the end of this movement of “Songs of the Cattle Drive.”

Warning: You may be familiar with modern renditions of these songs, so be prepared for some unexpectedly different sounding tunes and chords in these authentic 1916 versions.

These are Charles Russell’s paintings and the cowboy songs from John A. Lomax for this “Songs of the Cattle Drive” Movement:

Cowboy Sport – Roping a Wolf (1890) “The Cowboy”

The Bucker (1904) & A Bad One (1912) “The Zebra Dun”

Cowpunching Sometimes Spells Trouble (1889) “Little Joe, The Wrangler”

Roping the Renegade (1883) & Roping (1925) “Whoopee Ti Yi Yo, Git Along Little Dogies”

1 Cowboy Sport – Roping a Wolf by Charles Russell (1890)

Cowboy Sport – Roping a Wolf | Charles M. Russell | 1890 | Oil on canvas | 20 x 35.75 inches

The wolf in Russell’s Cowboy Sport is having a bad day. Like so many cowboy songs, “The Cowboy” speaks of the daily life of a cowboy, and since it mentions a wolf (as the cowboys’ pastor), it seemed a fitting song for this painting.

My ceiling the sky, my floor is the grass,

My music is the lowing herds as they pass;

My books are the brooks, my sermons the stones;

My parson the wolf on his pulpit of bones.

2 The Bucker (1904) & A Bad One (1912), both by Charles Russell

The Bucker | Charles M. Russell | 1904 | Watercolor, pencil & gouache on paper | 16.25 x 12.25 inches

A Bad One | Charles M. Russell | 1912 | Pencil, watercolor and gouache on paper | 19.75 x 28.625 inches

Bucking broncos were one of Russell’s favorite subjects. They were also the source of amusement in cowboy songs like “The Zebra Dun” in which cowboys attempt to play a joke on a supposed ‘tenderfoot’. A zebra dun horse has a buckskin color and dark zebra stripes across his withers and around the forelegs, and was considered to be “the toughest, wickedest, most devlish-tempered brute that ever felt a cinch on his belly.” Here’s how the song describes the bucking zebra dun horse:

When the stranger hit the saddle, Old Dunny quit the earth

And traveled right straight up for all that he was worth.

A-pitching and a-squealing, a-having wall-eyed fits,

His hind feet perpendicular, his front ones in the bits.

We could see the tops of the mountains under Dunny every jump,

But the stranger he was growed there just like the camel’s hump…

Inspect Russell’s paintings to see if either horse matches the description of a zebra dun, and check out the perspective. Can you see “the tops of the mountains” under the jumping horse?

N. Howard “Jack” Thorp wrote the lyrics which were printed in his small 1908 collection, and also included in John Lomax’s book in 1916. Neither provided music for the words, but it was apparently sung to the traditional Irish tune, “Son of a Gambolier.” For the full story, read the lyrics at the end of the sheet music.

3 Cowpunching Sometimes Spells Trouble (1889) by Charles Russell

Charles M. Russell, Cowpunching Sometimes Spells Trouble, 1889, Oil on canvas, 26 x 41 inches

“Little Joe, The Wrangler” was a young stray Texan who suffered a fate that appears similar to what is happening to the unfortunate downed cowboy in Russell’s painting. His story mirrors that of many a young cowboy who left a difficult home life for the cattle trail (my great-grandfather, among them).

It’s Little Joe, the wrangler, he’ll never wrangle more,

His days with the remuda they are o’er;

’Twas a year ago last April when he rode into our camp, –

Just a little Texas stray and all alone…

He said that he had to leave his home, his pa had married twice;

And his new ma whipped him every day or two;

So he saddled up old Chaw one night and lit a shuck this way,

And he’s now trying to paddle his own canoe.

Hugh A. Everett

Little Joe’s story is similar to how my great-grandfather Hugh A. Everett ended up “on the trail”. During the Civil War, Hugh’s father died as a prisoner of war in a hospital in Knoxville, and their home in Georgia had been in the path of General Sheridan’s 1865 “March to the Sea.” So in 1871, the remaining family joined a wagon train headed to East Texas. In his late teens, Hugh’s uncles sent him to the mill to grind some corn, but on the way back, his horse stumbled while crossing a creek, and the sack of corn meal fell into the water. Determined that his uncles would not whip him again, Hugh headed west and joined Thomas and Sanford Hufstuttler’s cattle drive from Lampasas, TX going up the Goodnight and Loving trail. He vowed that if he ever made it back home, he would never go on another cattle drive. However, he must have been impressed with his trail bosses because he always referred to himself as “Sanford Thomas Hugh Allen Everett.” On his way back home through Johnson County, he met his future wife, Hattie Ann Hale, and well… the rest is family history. In his tintype photograph, Hugh resembles A. W. Lyman’s 1872 description of the Texas cowboy shared at the beginning of this blog post.

4 Roping the Renegade (1883) & Roping (1925) by Charles Russell

Roping the Renegade | Charles M. Russell | c. 1883 | Watercolor, pencil & gouache on paper | 12.5 x 16.625 inches

Charles M. Russell, Roping, ca.1925–1926, Gouache on paper, 19 1/4 inches x 15 inches

Who hasn’t heard, “Whoopee Ti Yi Yo, Git Along Little Dogies”? (Although Lomax’s 1916 version may not sound so familiar.) The song nicely wraps up the story of the cowboy on the cattle trail. John Lomax also quotes the song in his “Collector’s Note” at the beginning of his book:

… Still much misunderstood, [the cowboy] is often slandered, nearly always caricatured, both by the press and by the stage. Perhaps these songs, coming direct from the cowboy’s experience, giving vent to his careless and his tender emotions, will afford future generations a truer conception of what he really was than is now possessed by those who know him only through highly colored romances.

…

The changing and romantic West of the early days lives mainly in story and in song. The last figure to vanish is the cowboy, the animating spirit of the vanishing era. He sits his horse easily as he rides through a wide valley, enclosed by mountains, clad in the hazy purple of coming night, – with his face turned steadily down the long, long road, “the road that the sun goes down.” Dauntless, reckless, without the unearthly purity of Sir Galahad though as gentle to a pure woman as King Arthur, he is truly a knight of the twentieth century. A vagrant puff of wind shakes a corner of the crimson handkerchief knotted loosely at his throat; the thud of his pony’s feet mingling with the jingling of his spurs is borne back; and as the careless, gracious, lovable figure disappears over the divide, the breeze brings to the ears, faint and far yet cheery still, the refrain of a cowboy song:

Whoopee ti yi yo, git along, little dogies;

It’s my misfortune and none of your own.

Whoopee ti yi yo, git along, little dogies;

For you know Wyoming will be your new home.

Coda

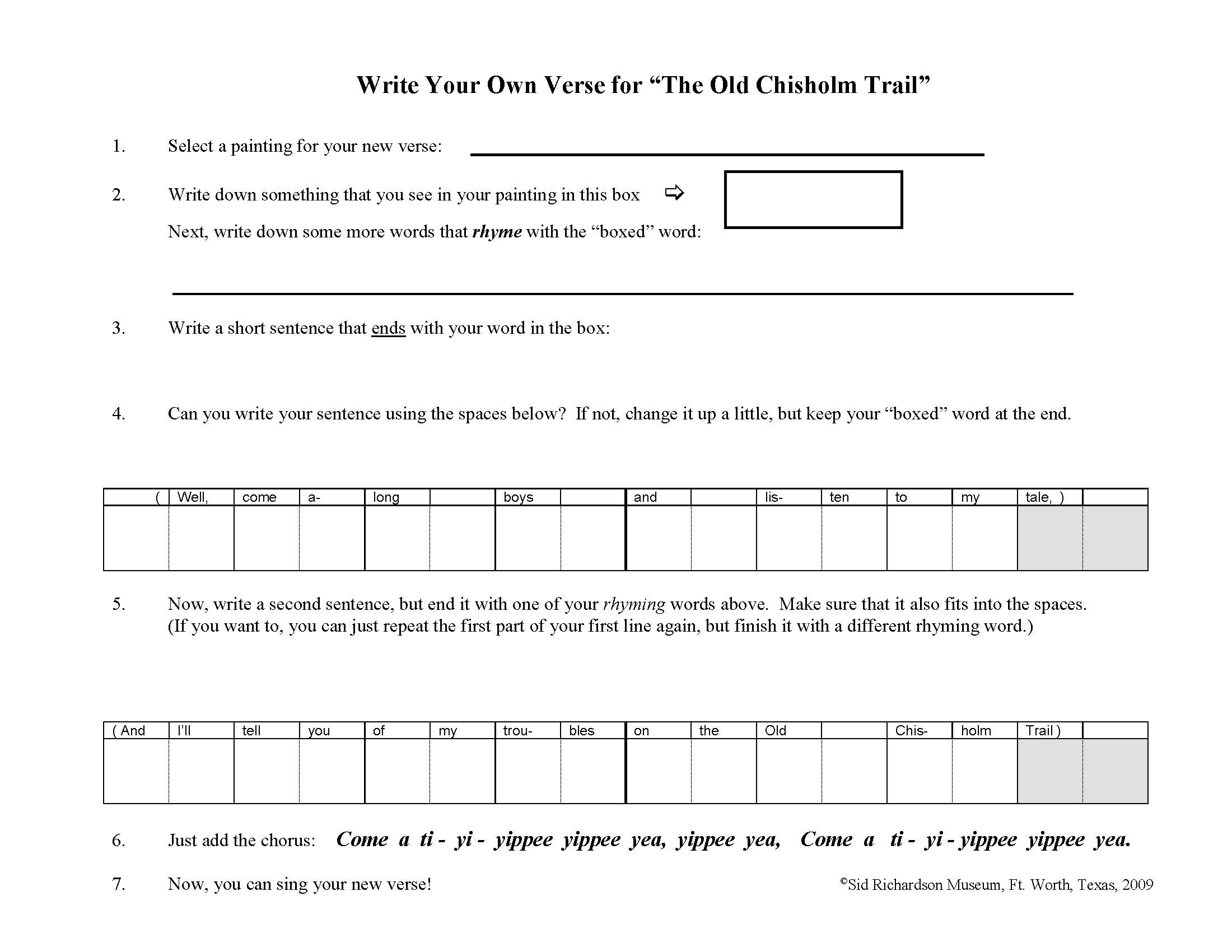

Write Your Own Cowboy Verse!

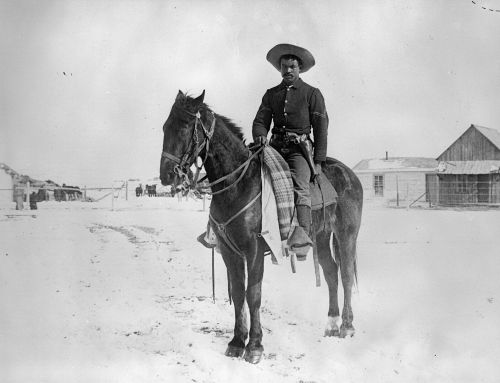

Self-Portrait On A Horse | Frederic Remington | c. 1890 | Oil on canvas | 29.1875 x 19.375 inches

In his self-portrait, Frederic Remington portrays himself in a slim, heroic stance, somewhere out on the trail – maybe even, the old Chisholm Trail.

You may be more familiar with this version of “The Old Chisholm Trail”. The verses of the song are a kind of ‘Cowboy Haiku’, i.e., very short, and in a specific format. We have included a worksheet that you can use to create your own “Chisholm Trail” verse. Just pick out a cowboy painting from the Sid Richardson Museum website, review the worksheet, and git started! Feel free to post your verse in the comments section below, or on our social media sites.

Leave A Comment