*The following is part of a series of blog posts researched and written by Mark Clardy, SRM Docent and independent scholar.*

Symphony of Native America

Movement 2

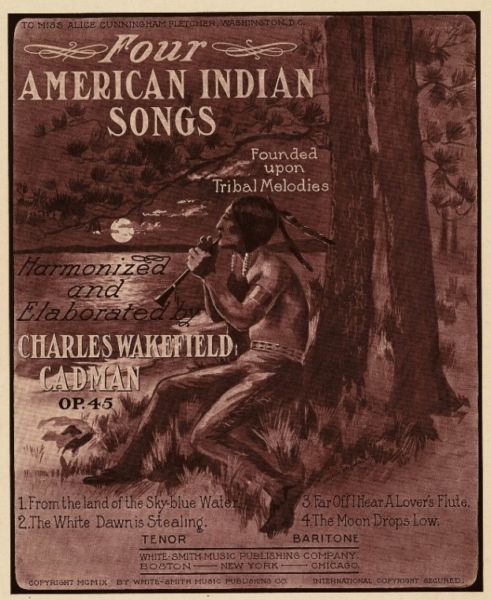

Four American Indian Songs by Charles Wakefield Cadman

Searching for Sounds of the New World

Charles Wakefield Cadman, Four American Indian Songs, 1909

By the close of the 19th century, the search for a distinctly “American” musical sound was well underway; but oddly, its most ardent advocate was a Bohemian. While serving as the Director for the National Conservatory of Music of America in New York, Antonín Dvořák argued that American composers should turn to Negro spirituals and the music of the American Indians for a truly American sound.

A few composers followed Dvořák’s lead, and began incorporating Indian melodic material into their “Indianist” compositions. Among them were: Edward MacDowell, Amy Beach, Arthur Farwell, Carlos Troyer, and Harvey Washington Loomis. The most famous Indianist composer (through no fault of his own) was Charles Wakefield Cadman.

Cadman was the music editor for the Pittsburgh Dispatch and a part-time composer who teamed up with neighbor Nelle Richmond Eberhart, the lyricist for most of his works. Her poetry sprang from her own imagination, and bore no relation to any original American Indian texts. Unlike most of his fellow Indianist composers who (more or less) maintained the melody and rhythm of the Native American sources, Cadman was more concerned with the marketability of the final product, and edited the American Indian melodies to fit his musical goals.

As luck would have it, when Cadman published Four American Indian Songs, Op. 45, in early 1909, the very famous soprano Lillian Nordica added one of his new songs, “From the Land of the Sky-blue Water”, to her 1909 national concert tour repertoire. Sales took off, and Cadman became a very popular composer and sought-after “expert” lecturer on American Indian music. Inexpensive original copies of Four American Indian Songs are still easy to find.

In this movement of our on-going “Symphony of Native America”, we’ll listen to Cadman’s four songs and examine how they relate to four paintings at the Sid Richardson Museum. They are:

1 “From the Land of the Sky-blue Water” The Marriage Ceremony

2 “The White Dawn Is Stealing” The Pow Wow

3 “Far Off I Hear a Lover’s Flute” The Love Call

4 “The Moon Drops Low” The Grub Pile

“From the Land of the Sky-blue Water” & The Marriage Ceremony by C. M. Russell

The Marriage Ceremony (Indian Love Call), painted by Charlie Russell in 1894, appears to depict a somewhat straightforward courtship method of the Plains tribes, i.e., the acquisition of a wife by capturing an unescorted indigenous maiden. So does it depict courtship, or capture, or maybe both?

The Marriage Ceremony (Indian Love Call) | Charles M. Russell | 1894 | Oil on cardboard | 18.5 x 24.625 inches

American ethnologist Alice Fletcher studied and documented American Indian culture and recorded several love songs from the Omaha tribe on wax cylinders. Digitized recordings for three of these songs are on the American Folklife Center’s Library of Congress website, under the name Bice’WaaN. Fletcher published transcriptions of five Omaha love songs in A Study of Omaha Indian Music in 1893, using an older spelling. One of them, “Be-Thae Wa-An” Song #86 (as Fillmore’s harmonized version, p. 146), became the basis for the most famous song of the entire Indianist Movement: “From the Land of the Sky-Blue Water”. As you listen to Cadman’s song, see if you can detect how it differs from the melody of the original Omaha love song.

Fletcher’s description of how the love songs were used (p. 53) is quite similar to the scene in Charlie Russell’s The Marriage Ceremony (Indian Love Call):

The Be-thae wa-an, or love songs, are sung in the early morning about daybreak. The few words that are set to the music refer to the time of day. The young man seeks a vantage point and there sings his lay, the girl within the tent hears him and perchance by and by they meet at the spring, the trysting place of lovers.

In her second book, Fletcher included “A Trysting Love Song” (a “tryst” was a popular term for risqué encounters in early 20th century love songs). She also included the following description of an observed courtship (p. 34-35):

One morning I rose from my blankets and stepped out under the broad dome of the sky, while all about me in their shadowy tents the people slept. I wandered toward a glen, down which the water from a little spring hurried to the brook. As I sat among the fresh undergrowth, I watched the stars grow dim and the thin line of smoke rising from the tents, telling that the mother had risen to blow the embers to a blaze and to put another stick or two upon the fire.

As I sat, thinking a multitude of thoughts, I heard a rustling upon the hill opposite me. Then there was a silence, quickly broken by movements in another direction; while from the hill came the clear voice of a young man singing. In a moment more, two women, whom I recognized as aunt and niece, appeared at the spring, the one elderly, the other young and pretty; but the singer was still invisible. The cadences of the song were blithe and glad, like the birds and the breezes laden with summer fragrance. The words, “I see them coming!” carried a double meaning. The girl for whom he had waited was in truth coming, but to the singer was also coming the delight of growing love and abundant hope.

The women filled their water vessels. The elder took no note of the song, but turned steadily toward the home path. The eyes of the maiden had been slyly searching the hillside as she slowly neared the spring and dipped up the sparkling water. Now, as the aunt walked away, the song ceased; and a light rustling followed, as the lover, bounding down the hill, leaped the brook and was at the side of the girl. A few hasty words, a call from the aunt, a lingering parting, and I was alone again. The brook went babbling on, but telling no tales, the birds were busy with their own affairs, and the sunbeams winked brightly through the leaves. The little rift, giving a glimpse of the inner life of two souls, had closed and left no outward sign; and yet the difference!

“The White Dawn is Stealing” & The Pow Wow by Wm. G. Gaul

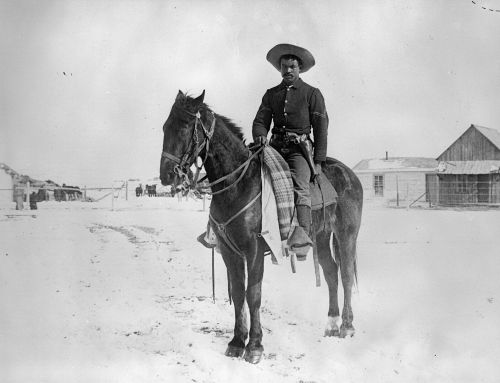

William Gilbert Gaul painted The Pow Wow likely while working as a reporter for the US Census record of 1890 to depict the actual conditions of the Dakota people of the Standing Rock Reservation in a time of great changes. The government had just opened half of the Dakota Reservation to Anglo settlers, and split the remaining nine million acres into smaller reservations. Later, in December, Chief Sitting Bull would be killed in a dawn raid at Standing Rock. In three more years, Frederick Turner would declare the frontier closed.

The painting is one of the earliest in the Sid Richardson collection. It shows how the old ways of life had long since passed. Look at the clothing, the canvas teepee, the wagon, the coffee pot on the campfire, even the drying beef on the line. The buffalo herds were gone, so the meat was from government issued rations. The women’s roles appear to have changed little, but what functions do the former hunters and warriors have left?

The Pow-Wow | William G. Gaul | c. 1890 | Oil on canvas | 18.125 x 24.125 inches

For the second of his Four American Indian Songs, Cadman turned to songs of the Dakota tribe with, “The White Dawn Is Stealing”, which is the only one of the four songs that is not based on music from the Omaha tribe. Instead, it is based on a Dakota melody that was recorded by Rev. Stephen Return Riggs (Dakota melody No. 2.). Cadman found the tune in Theodore Baker’s ground-breaking 1882 PhD dissertation: On the Music of the North American Indians (published in German). Having worked for several years among the Dakota tribe in Minnesota and at Fort Sully, Dakota Territory, Rev. Riggs first recorded the tune forty years earlier, not far from where Gaul painted The Pow Wow in 1890. Maybe the men in the painting were singing it to their busy wives?

“Far Off I Hear A Lover’s Flute” & The Love Call by F. S. Remington

The sound of a lone flute lies just beneath the brush strokes in The Love Call, a nocturne by Frederic Remington. Among the Plains Indians, the flute is traditionally played only by men. Their goal is to attract a potential wife, hence the juxtaposition of the flute player and not-too-distant teepees in the background.

The Love Call | Frederic Remington | 1909 | Oil on canvas | 31 x 28 inches

The source tune for Cadman’s third song is “Love Call” (Fletcher, 1900, p. 68), a tune which Fletcher says is to be played on the “native flageolet” or Native American Flute (technically referred to as a duct flute, like a recorder.) Cadman opens his third song “Far Off I Hear A Lover’s Flute” with this unaccompanied flute melody before introducing the vocals and piano harmonization.

Look closely at the face of Remington’s flute player, and compare it with the Indian’s face in the illustration on the opening page of Cadman’s song collection. Do you see any resemblance? (Ignore the fact that his flute has a flared bell like an oboe – a fact that greatly irritated Charles Cadman (Beth Levy, 2012, p. 386, note 17.)

Could Remington have seen Cadman’s sheet music before painting The Love Call? Sales of Cadman’s sheet music would have soared after Lillian Nordica’s national tour performances, beginning in early 1909. Frederic Remington moved from New Rochelle, New York, to Ridgefield, Connecticut (about 35 miles) on May 17, 1909, and painted The Love Call there on July 6, 1909. Being in the cultural center of the U. S., and being interested in all things “Indian”, could Remington have seen the sheet music for Cadman’s popular song before painting The Love Call? Hmmmm…

If you listen closely to Remington’s painting, you just might hear “The Love Call” as the night wind whistles through the trees above.

“The Moon Drops Low” & The Grub Pile by C. M. Russell

In The Grub Pile (1890), Charlie Russell painted a contemplative Cree Indian smoking his pipe by the campfire as the cold night falls. In many Native American cultures, smoking the pipe was a ritual accompanied by songs.

Grubpile (The Evening Pipe) | Charles M. Russell | 1890 | Oil on canvas | 9.625 x 16.375 inches

“Hae-Thu-Ska Wa-An” is a song of the Omaha He-dhu-shka Society, first published in Alice Fletcher’s 1893 book (#12, p. 87; Fillmore’s harmonization used cross rhythms in 6/8 and 4/8). It also appears in Indian Story and Song from North America (1900), as “Prayer of the Warriors Before Smoking the Pipe”, with an old man’s explanation of the significance of the song (p. 8-9): “When the Leader’s face is painted… he offers the pipe to Wa-kon-da (god). The words of the song then sung mean: ‘Wa-kon-da, we offer this pipe (the symbol of our unity as a society). Accept it (and us).’ All the members must join in singing this prayer, and afterward all must smoke the pipe.”

Cadman adapted the Omaha melody for his fourth song “The Moon Drops Low”. However, as with all of Nelle Eberhart’s poetry, the song’s lyrics are in no way related to the original Omaha text. Instead, she clearly expressed the idea of “the doomed Red Race” in a somewhat disturbing manner which is accentuated by the strident tension in the discordant harmonies and minor key:

The moon drops low that once soared high, As an eagle soars in the morning sky;

And the deep dark lies like a death-web spun, ‘Twixt the setting moon and the rising sun.

Our glory sets like the sinking moon; The Red Man’s Race shall be perish’d soon;

Our feet shall trip where the web is spun, For no dawn shall be ours, and no rising sun.

It was, in fact, too much for Alice Fletcher’s Omaha collaborator Francis La Flesche. Beth Levy wrote:

“…It can hardly be surprising that, some years later, when Francis La Flesche (son of an Omaha woman and co-author of Fletcher’s Omaha research) advised Cadman on Indian music, he apparently told the composer that this song was ‘not representative of the way an Indian sees himself.’ “ (Beth E. Levy, “ ‘In the Glory of the Sunset’: Arthur Farwell, Charles Wakefield Cadman, and Indianism in American Music,” repurcussions, 1996, Vol 5, Nos. 1-2, p. 155-7; quoting Arolovine Wu’s book about Constance Eberhart.)

In the next Movement in the Symphony of Native America, we will cover the paintings and songs of the buffalo hunt.

[…] was paired with the second song of Charles Wakefield Cadman’s Four American Indian Songs; see the second post in this series. For more on Gaul, the Dakota tribe, and the Standing Rock Reservation, see the previous blogs, A […]