From September 15 – October 15, as a nation we observe and celebrate National Hispanic Heritage Month. This time is an opportunity to recognize and honor the histories, cultures, and contributions of fellow Americans whose families and ancestors immigrated from Spain, Mexico, the Caribbean, and Central & South America.

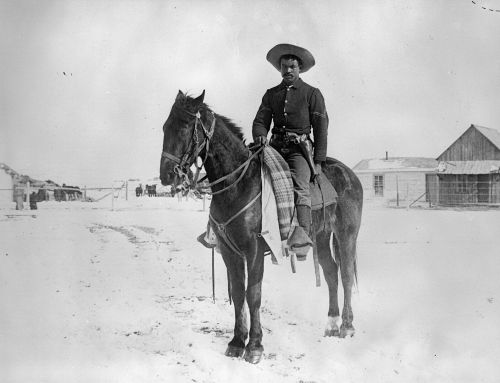

By Doerr & Jacobson — Photographer – Original source: Robert N. Dennis collection of stereoscopic views. / United States. / States / Texas. / Stereoscopic views of San Antonio, Texas. (Approx. 72,000 stereoscopic views : 10 x 18 cm. or smaller.) digital record. This image is available from the New York Public Library’s Digital Library under the digital ID G92F039_034F: digitalgallery.nypl.org → digitalcollections.nypl.org Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10083425

In the American West, Hispanic culture, particularly the tradition of the vaquero, helped establish the foundation for much of cowboy life as we know it today. Working alongside the vaqueros, Anglo cowboys learned and adopted their tools and techniques. Adoption of the vaquero practices was so widespread, especially in the Lone Star state, that many of the terms used have become practically “Texan.”

Here’s just a handful of the Spanish words commonly used in Texas:

Armadillo (literally, “the little armed one”)

Bronco (means “wild” or “rough” or “rude”)

Burrito (literally “little donkey”)

Chaps (from Mexican Spanish chaparreras)

Hammock (from jamaca, Caribbean Spanish word)

Lariat (from la reata, braided rawhide rope)

Lasso (from lazo)

Mustang (from mesteñas, – a wild horse)

Patio (In Spanish, an inner garden or courtyard.)

Remuda (regionalism for a relay of horses)

Rodeo (roundup / show of skills – verb to encircle)

Sombrero (sombra, “shade,” – any kind of hat)

Wrangler (caballerano, one who grooms horses)

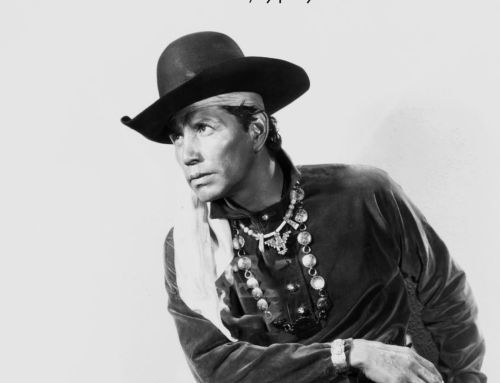

Frederic Remington | The Cow Puncher | 1901 | Oil (black & white) on canvas | 28 7/8 inches x 19 inches

Frederic Remington was well aware of the vaquero and its influence on the Anglo cowboys. He once chided his friend and Western writer Owen Wister for having claimed Anglo-Saxon origin of the cowboy in Wister’s article “The Evolution of the Cow-Puncher,” which appeared in Harper’s Monthly in 1895. In fact, Wister traced the genealogy of the Western cowboy to that of the knights of medieval Europe. In a letter to Wister, Remington corrected his friend, noting that the traditions of the cowboy were of Latin origin and evolved from the vaqueros of Mexico and Texas.

Not only did Remington witness the cowboy in action during his journeys out West, but the artist also traveled to Mexico in 1889 and later in 1893. He spent weeks sketching and photographing vaqueros and their horses, providing the artist with an array of firsthand material for his work.

Vaquero de Fort Worth | 2012 |Thomas Bustos and David Newton | Bronze | North Main Street and Central Avenue Plaza | Photo courtesy of Fort Worth Public Art

Fort Worth celebrates its own ties to the vaquero tradition, and in 2012 the city commemorated a part of its Hispanic history with the installation of Vaquero de Fort Worth. The artists David Newton and Tomas Bustos were sensitive to the importance of this piece and paid careful attention to the historical accuracy of each detail of the vaquero. Now a part of the city-wide public art collection, this bronze sculpture overlooks the historic Northside, which is home to the Fort Worth Stockyards district, an area that developed due the success of the cattle business.

Vaquero de Fort Worth, detail

A rich, and little known history. I’m still living the life. Yo soy Hispano y Vaquero.

[…] Vaquero: In Texas and throughout the West, the tradition of the vaquero in Hispanic culture helped shape cowboy life and lore as we know it today. Adoption of vaquero practices was so widespread that many of their words— or adaptations of them—are well-known in Texas culture today – bronco, lasso, chaps, lariat, and rodeo, among others. Today, Fort Worth celebrates its own ties to the vaquero tradition in its public arts collection with the 2012 bronze statue Vaquero de Fort Worth by artists David Newton and Tomas Bustos, overlooking an area that developed due to the success of the cattle business. Further information about the importance and vitality of vaqueros is available via the The Sid Richardson Museum blog post “Viva El Vaquero!”. […]

Proud of our race our heritage and our talents.