As we prepare to reopen the museum to the public on June 7, 2021, we are pleased to present a fresh exhibit both in person and virtually! This thematic installation features works from the Sid Richardson Museum displayed to provide new contexts and renewed insights into the collection. The works are grouped around four themes: The Bison and Plains Indian Culture, Western Archetypes, Cowboys and Native Americans, and finally Twilight into Night.

Installation of Picturing the American West exhibit

While the collection holds a comprehensive group of works by Frederic Remington and Charles Russell, who therefore dominate this exhibit, the core collection is complemented by a significant group of paintings by other western artists from the late nineteenth to the early twentieth centuries. Augmented by a small selection of bronzes by both Remington and Russell on loan from a private collection, this exhibit is an opportunity to view the works of art in relation to each other based on subject and setting and therefore invite you, the viewer, to consider the collection from new perspectives.

The Bison and the Plains Indian

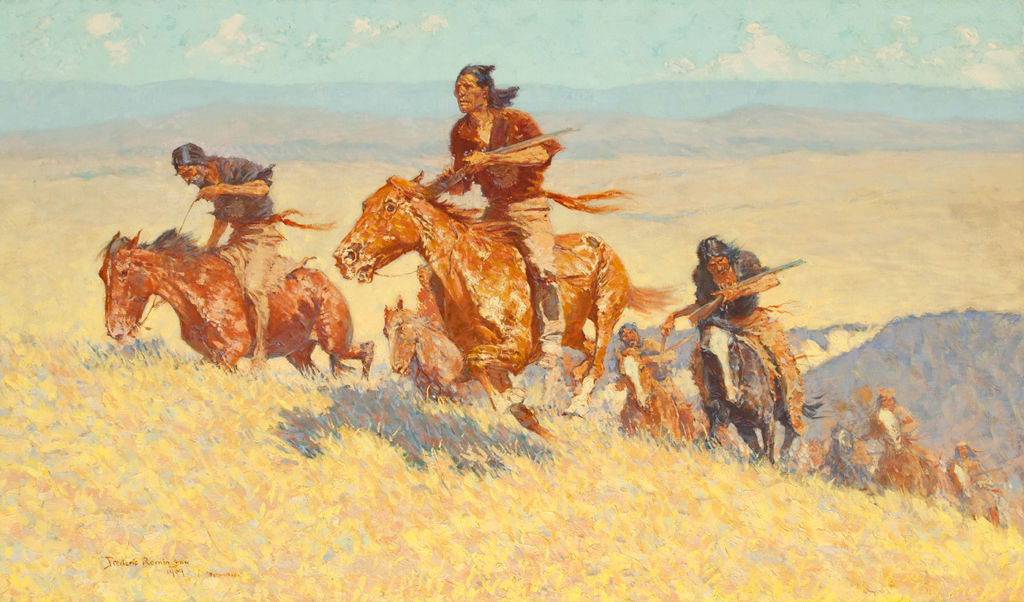

Buffalo Runners—Big Horn Basin | Frederic Remington | 1909 | Oil on canvas | 30.125 x 51.125 inches

Central to the lives of the Plains Indian peoples was the bison hunt. In this section of the exhibit most of the works are made by Charlie Russell who specialized in painting and sculpting the drama and energy of the hunt. Throughout his career, Russell made over 250 works that have “buffalo” in the title and at least 75 paintings featuring aspects of the actual hunt.

In the 1908 and 1909, Russell had the opportunity of a lifetime to participate in a buffalo round up of around 800 bison held by Michel Pablo on the Flathead Indian Reservation, which had been sold to the Canadian Government. Russell’s experience of up-close interaction and observation of the animals is evidenced in Wounded, which was made immediately following the second trip in 1909, and reveals his first-hand knowledge of harrowing experiences in trying to herd these immense animals.

Wounded (The Wounded Buffalo) | Charles M. Russell | 1909 | Oil on canvas | 19.975 x 30.125 inches

Russell personally did not approve of hunting for sport. His views of hunting are reflected in his titles of such scenes in which he refers to the wild game as “meat” as is evidenced in works on view in this section.

Wild Man’s Meat (Redman’s Meat) | Charles M. Russell | 1899 | Pencil, watercolor and gouache on paper | 21 x 30 inches

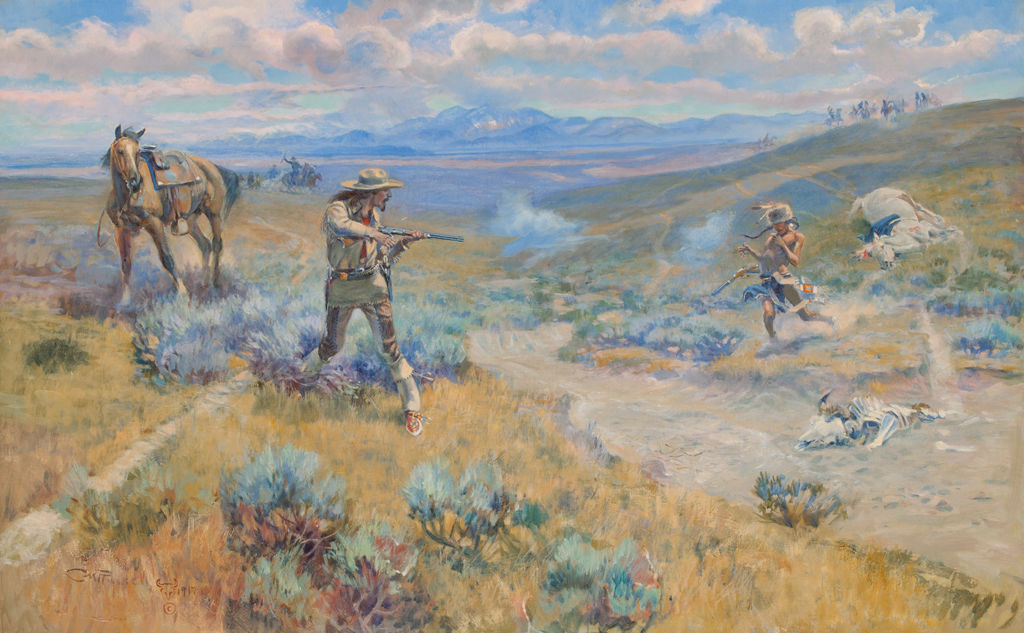

Cowboys and Native Americans

The conflicts between “cowboys and Indians” are more myth than reality developed out of the imagination of dime store novel authors and the popular “Westerns” of film and television. The majority of the conflicts that existed in the west arose between Indigenous peoples and white settlers moving West or the U.S. Government over broken treaties.

In reality, many who joined the cattle drives were of African, Mexican, and Indigenous descent. While today thought of as adventurous, solitary and embodying a certain western freedom, the real life of the cowboy was full of drudgery and monotony.

Attack on the Herd (Close Call) | Charles Schreyvogel | c. 1907 | Oil on canvas | 26.125 x 34.25 inches

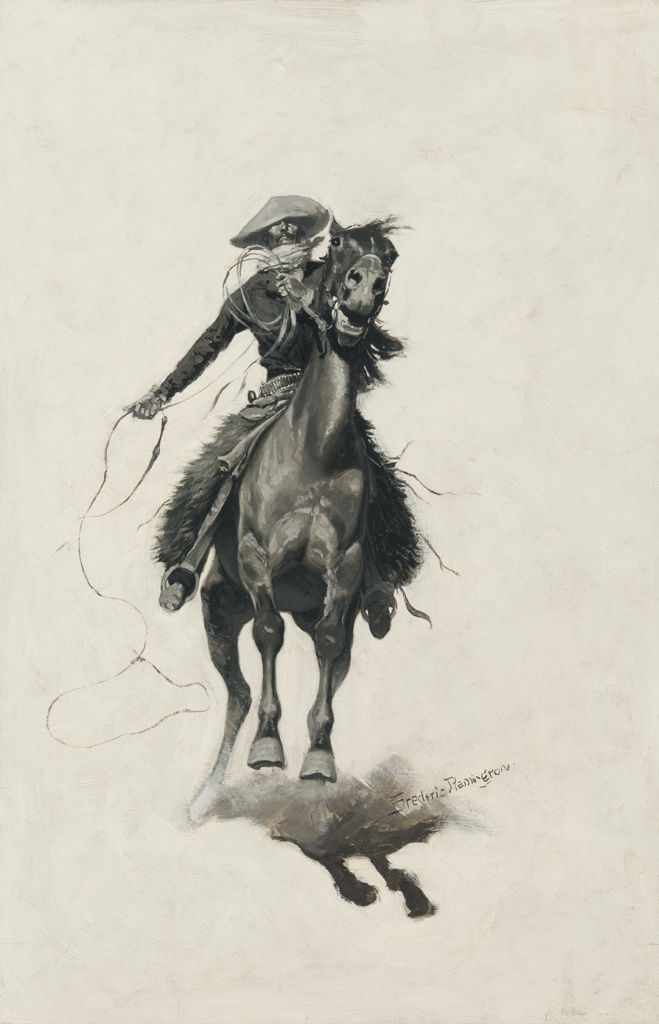

Cowboy culture in the American West developed from the Spanish tradition of the vaquero. Working alongside vaqueros, Anglo cowboys learned and adopted their tools and techniques. Frederic Remington was well aware of the vaquero and his influence on the Anglo cowboys. He once chided his friend and Western writer Owen Wister for tracing the genealogy of the Western cowboy to that of the knights of medieval Europe. In a letter to Wister, Remington corrected his friend, noting that the traditions of the cowboy were of Latin origin and evolved from Mexico and Texas.

The Cow Puncher | Frederic Remington | 1901 | Oil (black & white) on canvas | 28.875 x 19 inches

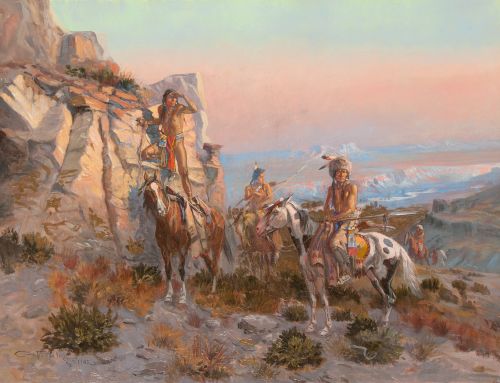

Both the cowboys and Native Americans depicted in our exhibit are painted from an Anglo perspective. The earliest depiction of Native Americans in this gallery is the Peter Moran painting Indian Encampment. It depicts the Bannock Indians who had settled on reservation lands in Southern Idaho just over a decade before. Gilbert Gaul and Peter Moran, both displayed in this exhibit, served as special agents in 1890 for the eleventh census, focusing on American Indians in the United States.

Indian Encampment | Peter Moran | c. 1880-81 | Oil on panel | 12.875 x 31 inches

The Pow-Wow | William G. Gaul | c. 1890 | Oil on canvas | 18.125 x 24.125 inches

Western Archetypes

At the center of this installation is an image of the man perhaps most closely associated with the west, William F. Cody. He earned his moniker, Buffalo Bill, by killing around 4,000 bison from 1867 to 1868. His Wild West Show began when the real west was coming to its close in 1883. By that time the days of bison hunts, mountain men, forty-niners and pony express riders were quickly fading into the past. Through newspaper articles, dime novels, and through his stage show, Cody created his own mythology that he then performed for close to thirty years to audiences around the world. In his own lifetime, Cody became a legend that young boys like Russell read about and idealized.

The figures shown in this section of the exhibit carved out the trails west from the expedition of Lewis and Clark to those who set out in search of fortune, and sped up communication across the continent. The actual time period of western expansion was relatively brief, lasting from around 1848 and the discovery of gold in California to the end of the 1880s, the demise of the buffalo and the closing of the open range by barbed wire. The stories and characters that developed from that era have come down to us through artists like Remington and Russell who were working at the turn of the 20th century.

Buffalo Bill’s Duel With Yellowhand | Charles M. Russell | 1917 | Oil on canvas | 29.875 x 47.875 inches

Remington remarked in 1908, “We fellows who are doing the ‘old America’ which is so fast passing will have an audience in posterity whether we do at present or not.” He created a cast of archetypal western heroes that he returned to again and again in his art from the cowboy, to the brave soldier, and the mountain man. These were who he described as, “Men with the bark on [who] die like the wild animals, unnaturally—unmourned, and even unthought of mostly.”

The Unknown Explorers | Frederic Remington | 1908 | Oil on canvas | 30 x 27.25 inches

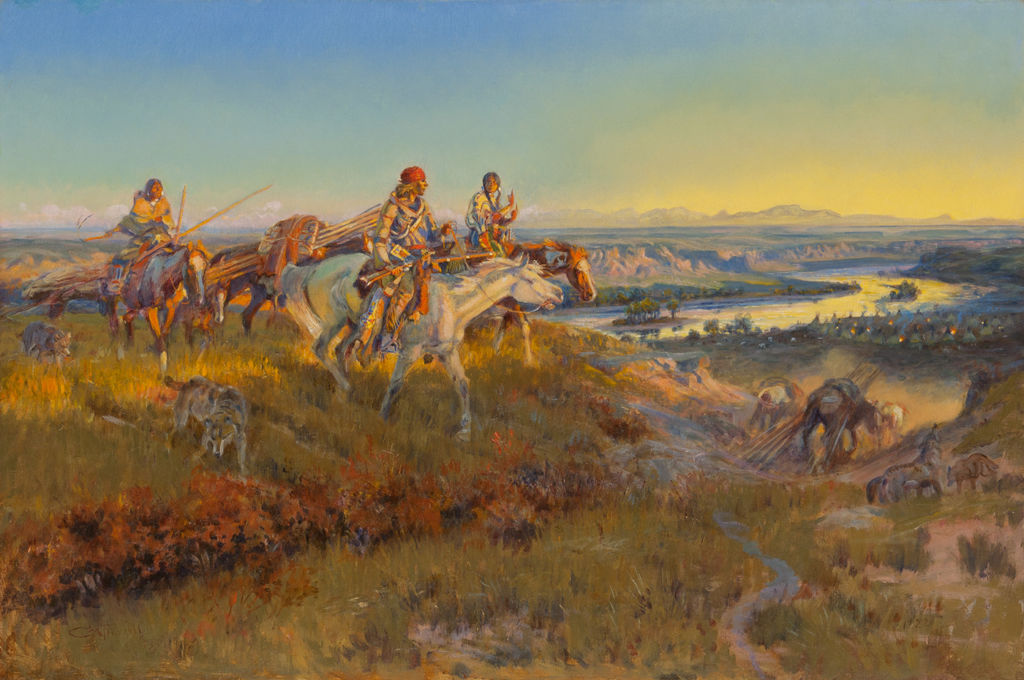

Twilight into Night

Sunset, twilight, and night have long been used metaphorically in works of art and were settings often employed by western artists to communicate their nostalgia for the passing of the Old West. Both Remington and Russell lamented that the west that figured so prominently in their narratives was long passed. While Russell had actually lived and worked in Montana as a cowboy, he witnessed the closing of the west. His exhibition that traveled around the country and to England he titled “The West That Has Passed.” In his later years, as his color palette brightened he increasingly displayed his narratives of the west under the fading light of day.

When White Men Turn Red | Charles M. Russell | 1922 | Oil on canvas | 24 x 36.25 inches

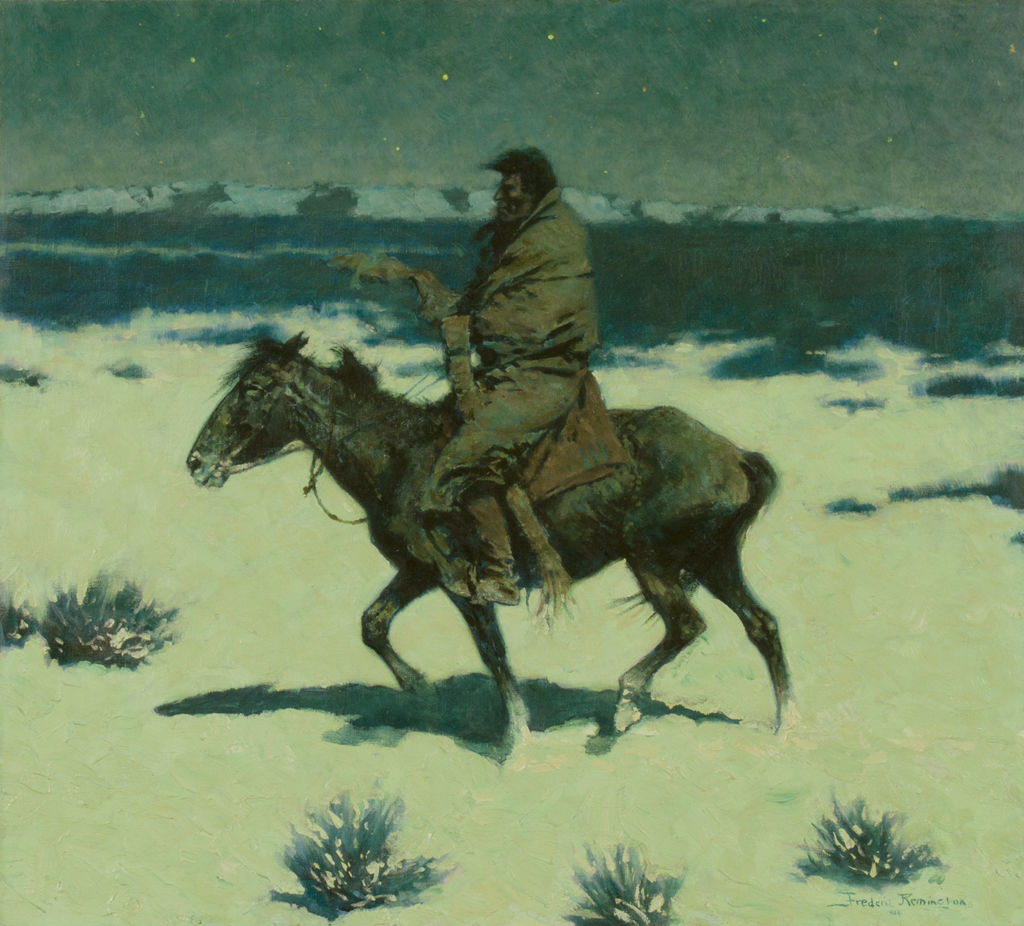

In 1900, Remington complained that the west he knew was all “brick buildings—derby hats and overhauls [sic]—it spoils my early illusions—and they are my capital.” In the last decade of his life he increasingly set his western narratives under the dark of night which can be read symbolically as his vision of the vanishing west. The passage of sunset into night can be seen in this exhibition as the golden glare of the end of day gives way to lavender shadows and descends into cool blues, inky blacks, and lurid greens.

The Luckless Hunter | Frederic Remington | 1909 | Oil on canvas | 26.875 x 28.875 inches

Make your FREE reservation today to visit Picturing the American West! Can’t join us in person? Explore our galleries virtually with our 360 degree virtual tour.

Leave A Comment