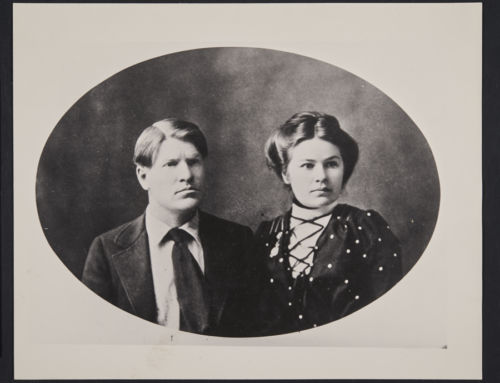

A few months ago, the museum hosted a lecture by Byron Price, Director of Charles M. Russell Center for the Study of Art of the American West at the University of Oklahoma. During the program, Price discussed Charles Russell’s depictions of wild animals, which comprise roughly a quarter of the artist’s total production of paintings, drawings and sculpture! Even when animals are not the principal focus of a particular work, their presence is often palpable in the skins, horns, bones and effigies the artist added to many scenes in the interest of authenticity and allegory. Byron Price’s presentation explored Russell’s animal art as a reflection of the artist’s world view, the ideas and values he embraced and the times in which he lived.

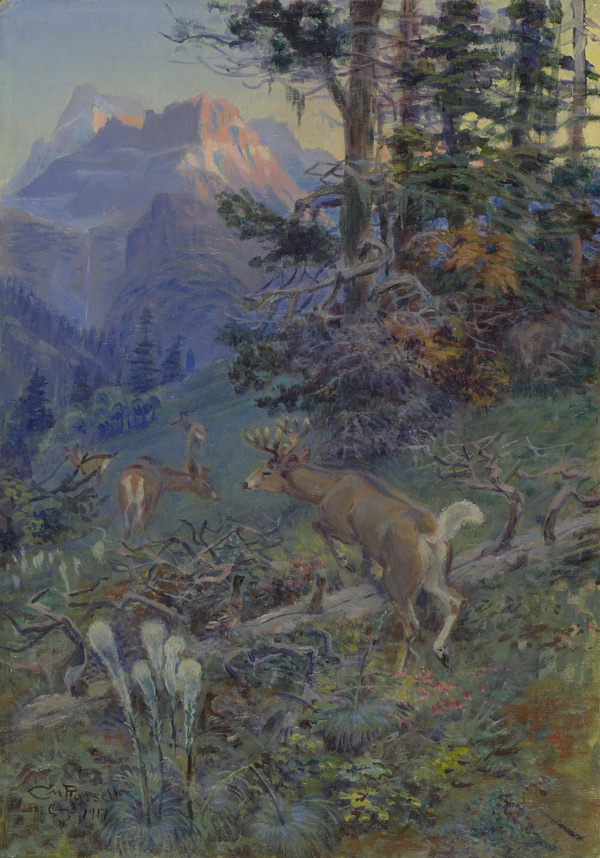

Charles M. Russell | Deer in Forest (White Tailed Deer) | 1917 | Oil on canvasboard | 14 inches x 9 7/8 inches

Charles M. Russell, Indians Hunting Buffalo (Wild Men’s Meat; Buffalo Hunt), 1894, Oil on canvas, 24 1/8 x 36 1/8 inches

Charles M. Russell | Buffalo Hunt | 1901 | Oil on canvas | 24 1/8 inches x 36 1/8 inches

Charles M. Russell | Guardian of the Herd (Nature’s Cattle; Buffalo Herd; Before the White Man Came) | 1899 | Watercolor, pencil & gouache on paper | 20 5/8 inches x 29 1/8 inches

Russell was always an admirer of Mother Nature. As a child, he developed a love & respect for many animals, and in particular, the American bison. Gather up all of Russell’s artworks, and you’ll find that over 250 of them have “buffalo” in the title. And the artist produced at least 75 paintings of bison hunts.

Growing up, Russell copied hunting scenes he found in books and magazines. One of his earliest influences includes the early American artist George Catlin. Catlin was one of the first American artists to travel West to document and paint the people, plants, and animals he encountered. This collection of work comprised what became known as Catlin’s Indian Gallery, which he exhibited throughout the U.S. and in Europe. (And you might remember Catlin’s work from our 2014-2015 exhibit Take Two: George Catlin Revisits the West.)

“Buffalo Chase––Bulls Protecting the Calves,” George Catlin (1796-1872), (Cartoon No. 153) Oil on card mounted on paperboard, 18 1/2 x 25 1/16 in., National Gallery of Art, Washington, Paul Mellon Collection

Another artist who made an early impact on Russell was German artist Carl Wimar. Wimar was known for his representations of Plains Indians and their buffalo hunts. Having settled in St. Louis, where he spent much of his career, Wimar’s work would have been visible to Russell in many public buildings around the city. (Russell was born and raised in St. Louis.)

Charles Ferdinand Wimar (American, b. Germany, 1828–1862), The Buffalo Hunt, 1860. Oil on canvas, 35 7/8 x 60 1/8″. Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Washington University in St. Louis. Gift of Dr. William Van Zandt, 1886.

Throughout his life, Russell enjoyed the company of hunters. When he first traveled to Montana as a teenager to fulfill his dreams of becoming a cowboy, Russell left his first job working on a sheep ranch to travel around the Judith Basin with mountain man Jake Hoover. Hoover was a skilled hunter and trapper and helped Russell get settled into life on the frontier.

Despite spending time with hunters, Russell himself never hunted. He always viewed hunting as a means to provide food. He did not approve of hunting for sport. His views of hunting are reflected in his titles of such scenes in which he refers to the wild game as “meat.” Examples include:

Fresh Meat, (c. 1880)

His Winter’s Meat, (c. 1890)

Wild Meat For Wild Men, (1890)

Charles M. Russell | Wild Man’s Meat (Redman’s Meat) | 1899 | Pencil, watercolor and gouache on paper | 21 inches x 30 inches

Bringing Home The Meat, (c. 1910)

Christmas Meat, (1915)

When Meat Was Plenty, (1915)

When Tracks Spell Meat, (1916)

Fighting Meat, (1919)

Meat’s Not Meat til Its in the Pan, (1915)

Likewise, one can use the artist’s titles as evidence of the evolution of Russell’s views on the activity once known as “wolfing.” In the late 19th century, due to attacks on livestock, a campaign against the great gray wolf was made and overtime the occupation of hunting, trapping, and poisoning these wolves became known as “wolfing.” Young cowboys like Charlie Russell would partake in these activities during the off season, as many states provided a bounty for the capture and killing of gray wolves. Russell later lamented his participation in poisoning wolves one season early in his cowboy career, an activity he said he regretted the rest of his life. One can witness the transformation of Russell’s views of “wolfing” from an activity of fun and sport with titles of early paintings like Cowboy Sport – Roping a Wolf (1890) to an understanding of the fatal effects of these pursuits in later titles like At Rope’s End (1909) or Death Loop (1912).

Charles M. Russell | Cowboy Sport – Roping a Wolf | 1890 | Oil on canvas | 20 inches x 35 3/4 inches

One thing remained true throughout Russell’s life – a belief in the superiority of what he called “Ma Nature.”

Charles Russell, Man’s Weapons Are Useless When Nature Goes Armed, 1916, Oil on canvas, 30 inches x 48 1/8 inches

[…] time. For those who are looking to escape to the great outdoors, camping is a fun way to enjoy “ma nature.” Charles Russell enjoyed being outdoors and went on several camping trips, including a few with […]

[…] time. For those who are looking to escape to the great outdoors, camping is a fun way to enjoy “ma nature.” Charles Russell enjoyed being outdoors and went on several camping trips, including a few with […]

[…] personally did not approve of hunting for sport. His views of hunting are reflected in his titles of such scenes in which he refers to the wild game as “meat” as is evidenced in works on view […]