Although known for his depictions of cowboys and American Indians, Charlie Russell gave much attention to the wildlife that surrounded him near his Montana homestead. In fact, compositions of wild animals comprise roughly a quarter of the artist’s total production and attracted avid patronage during his career. However, scholars have paid little attention to Russell’s wildlife art. A new exhibition hopes to change that.

On May 17, Harmless Hunter: The Wildlife Work of Charles M. Russell premieres at the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson, Wyoming before touring to the Rockwell Museum of Western Art in Corning, New York, the Sam Noble Museum in Norman, Oklahoma, and the CM Russell Museum in Great Falls, Montana. Organized by the National Museum of Wildlife Art and the Charles M. Russell Center for the Study of the Art of the American West, University of Oklahoma, Harmless Hunter will look at wildlife art as a reflection of the artist’s world and focus on Russell’s wildlife work, his feelings about the wild creatures he admired and the tenor of the times, and his celebration of the superiority of nature through sometimes dangerous, but frequently humorous, situations involving animal and human interaction.

Included in the exhibition are a few paintings from the Sid Richardson collection:

Charles M. Russell, Indians Hunting Buffalo (Wild Men’s Meat; Buffalo Hunt), 1894, Oil on canvas, 24 1/8 x 36 1/8 inches

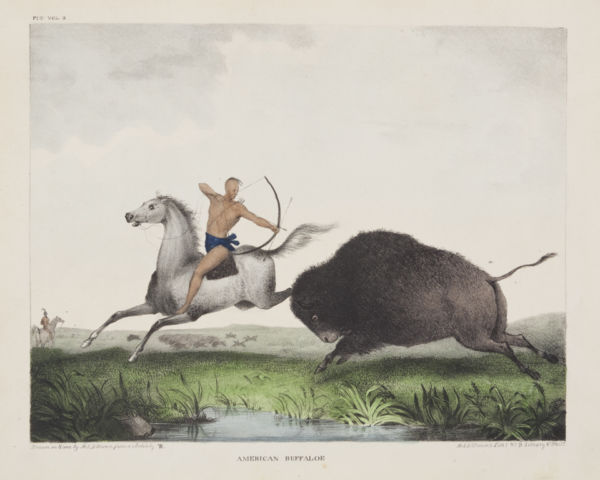

Titian Ramsay Peale, American Buffaloe, 1932, lithograph, Courtesy Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

Those familiar with Charles Russell’s work will immediately recognize this buffalo hunt as peculiar. The painting is more a flight of fancy than the kind of realistic observation expected of the cowboy artist. Russell may have been instructed by the man who commissioned the painting, Robert Vaughn, to model it after Titian Ramsay Peale’s 1832 lithograph, American Buffaloe. While the hunter is carefully modeled and convincing, both his position during the hunt and the appearance of his almost conventionalized white steed are more the product of an East Coast studio than of Russell’s knowing mind.

Charles M. Russell, He Tripped And Fell Into A Den On A Mother Bear And Her Cubs, 1910, Watercolor, pencil & gouache on paper, 17 x 14 inches

In 1910 Russell accepted a commission he came to regret, illustrating Mrs. Carie Adell Strahorn’s book Fifteen Thousand Miles by Stage: A Woman’s Unique Experience during Thirty Years of Path Finding and Pioneering from the Missouri to the Pacific and from Alaska to Mexico. Mrs. Strahorn’s stage coaching days with her husband qualified her as a bona fide pioneer and endowed her with an imperious manner. She set up camp near Charlie’s summer retreat on Lake McDonald and gave him the benefit of her advice. The painting illustrates a story Mrs. Strahorn told second hand about a man from Challis, Idaho, who set out one afternoon for a few hours of hunting with his dog and inadvertently stumbled into a bear’s den. He was badly mauled by the protective mother before his faithful dog distracted her long enough to allow him to crawl away. At last the bear ambled off to rejoin her cubs, and the dog, in the best tradition of Lassie, ran to town and brought back help.

Like buffalo, bears fascinated Russell. He incorporated them in several large action paintings and sculpted them frequently.

Charles Russell, Man’s Weapons Are Useless When Nature Goes Armed, 1916, Oil on canvas, 30 inches x 48 1/8 inches

While Russell painted buffalo and bear in profusion as symbols of the untamed West, he also loved nature’s smaller creatures, from the prairie dog to the field mouse and, as this humorous tribute suggests, had nothing but respect for the lowly skunk. Two hunters return at dusk after a day in the field to find their camp ransacked and their evening meal of pork and beans partially devoured by an invading duo that they can repel only at the risk of having their nest fouled. This amusing oil was inscribed as a thank you to Russell’s good friend, Howard Eaton, a pioneer dude rancher, after Russell rode with Eaton on a particularly memorable trip through Arizona and along the Grand Canyon in October, 1916.

Curated by Dr. Byron Price, Director of the Charles M. Russell Center, Harmless Hunter is sure to further understanding of Russell’s oeuvre. We’re excited to be able to share our collection with new audiences, expanding the reach of the Museum’s mission to educate, engage and inspire visitors to find meaning, value and enjoyment in Sid Richardson’s collection of paintings of the American West. Not able to make it to any of the exhibition sites? Visit our current exhibition, Western Treasures, and delight in the many other depictions of wildlife in the work of Russell, Remington, and their contemporaries.

[…] few months ago, the museum hosted a lecture by Byron Price, Director of Charles M. Russell Center for the Study of Art of the American West at the …. During the program, Price discussed Charles Russell’s depictions of wild animals, which […]

[…] personally did not approve of hunting for sport. His views of hunting are reflected in his titles of such scenes in which he refers to the wild […]