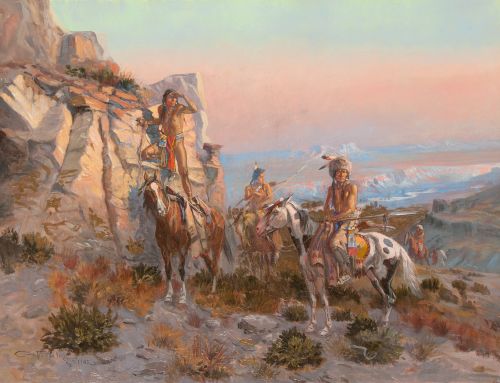

The museum made a recent discovery about an artwork from the collection as a result of one of our public programs, Tea & Talk. Designed to help us slow down the art looking experience by spending 10, 20, or even 30 minutes with one work of art. Tea & Talk engages participants through shared conversation about what we see. During a recent virtual Tea & Talk with Peter Moran’s c. 1880-81 oil painting Indian Encampment, the conversation focused on the large number of horses in the painting, leading some to speculate that the Indigenous people in the painting may have recently captured a group of wild horses. That speculation led to another observation that the central figure, wrapped in the red blanket in front of the white horse might be “trying to break it or subdue it”. Likewise, there were many questions about other details in the painting: why do the tipi-like structures have twig-like branches sticking out? What does the red blanket on the central figure signify? Why are the horses tied up in that formation? What are we looking at in this painting?

Indian Encampment | Peter Moran | c. 1880-81 | Oil on panel | 12.875 x 31 inches

Over the almost 80 years the painting has been in the collection, little has been written about the work. Following our discussion, the museum’s director, Scott Winterrowd, set off down a rabbit hole of research. Let’s see what he discovered.

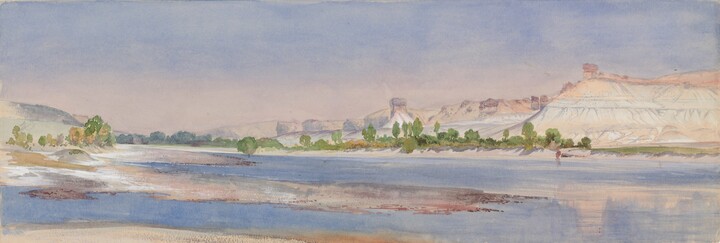

Peter Moran is the youngest brother of the well-known Western landscape painter, Thomas Moran. Like his older brother, Peter became an artist and grew to prominence as an etcher. In 1879, Peter accompanied Thomas on a trip out west sponsored by the Union Pacific Railroad. Between the end of July and mid-September, the two brothers traveled by train to Lake Tahoe, California and meandered canyon by canyon toward Salt Lake City, Utah. They then traveled to Fort Hall, Idaho, where they embarked on an excursion to the Teton Range in Wyoming, before returning to Idaho and then taking the train back east from Green River, Wyoming.[1]

Peter Moran, Cliffs Along the Green River, 1879, Transparent and opaque watercolor and graphite on tan paper, 19 x 6 5/8 in., 1965.82, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

Only a month-and-a-half later in November, Peter exhibited works made from his summer sketches as a member of the Philadelphia Society of Artists exhibition held at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. One of the works exhibited was noted as sold in both The New York Times and New York Tribune in January 1880, and titled Bannock Indians Breaking a Pony.

Indian Encampment has long been assumed to have been made around 1880 or 1881 following the brothers’ trip to the West in 1879. During their expedition, they had encountered members of the Bannock tribe. The Bannock were originally Northern Paiute but are more culturally affiliated with the Northern Shoshone. The Shoshones and Bannocks entered into peace treaties in 1863 and 1868, known today as the Fort Bridger Treaty. Their traditional lands include present-day Idaho, Oregon, Nevada, Utah, Wyoming, Montana, and into Canada. Since 1868, they are enrolled in the federally recognized Shoshone-Bannock Tribes of the Fort Hall Reservation of Idaho, located near the town of Pocatello in southeastern Idaho.[2]

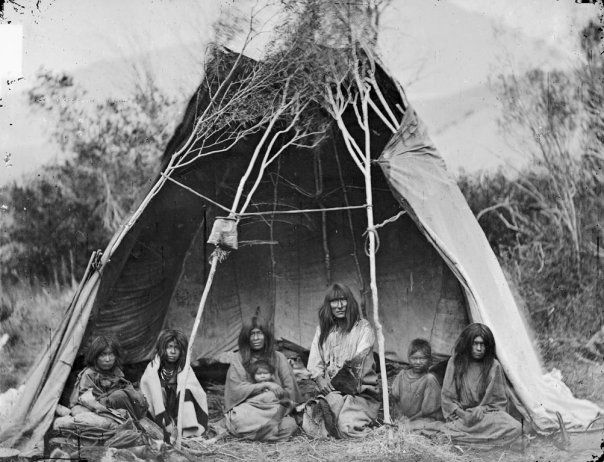

A Bannock family in camp at the head of Medicine Lodge Creek, Idaho, in 1871

Historically, the Bannock were introduced to the horse in the mid-18th century, and the tribe became known as people of the horse, developing a strong horse culture that allowed them to travel widely and have a large range of territory.[3] Fur traders during this period noted that the Bannock were quite proficient at acquiring horses. In Peter Moran’s painting in the museum’s collection, we see several groups of horses, many of which appear to be tied up to posts. How were these horses acquired? Are they waiting to be trained much like the white horse being handled by the figure wearing the red blanket?

Peter Moran, Indian Encampment, detail of horses

During the discussion, participants noted the structures lining the background that resemble tipis. Some of the participants commented that after looking closer, many of the structures appear to have branches sticking out of the tops, or were made entirely from brush. After some further research, we learned that these structures are called wickiups.

Peter Moran, detail of structures on left

Peter Moran, detail of structures on right

One of the common dwellings for the Bannock people during this time was wickiups, which were used mostly during the summer months. Wickiups were huts made from brush and reeds over pole frames. In the winter, these pole frames would likely be covered with tule rush mats and earth.

Bannock Indians with wickiup; Photographer unknown; 1871; Yellowstone National Park Photo Collection

Bannock wickiup; Photographer unknown; 1871; Yellowstone National Park Photo Collection

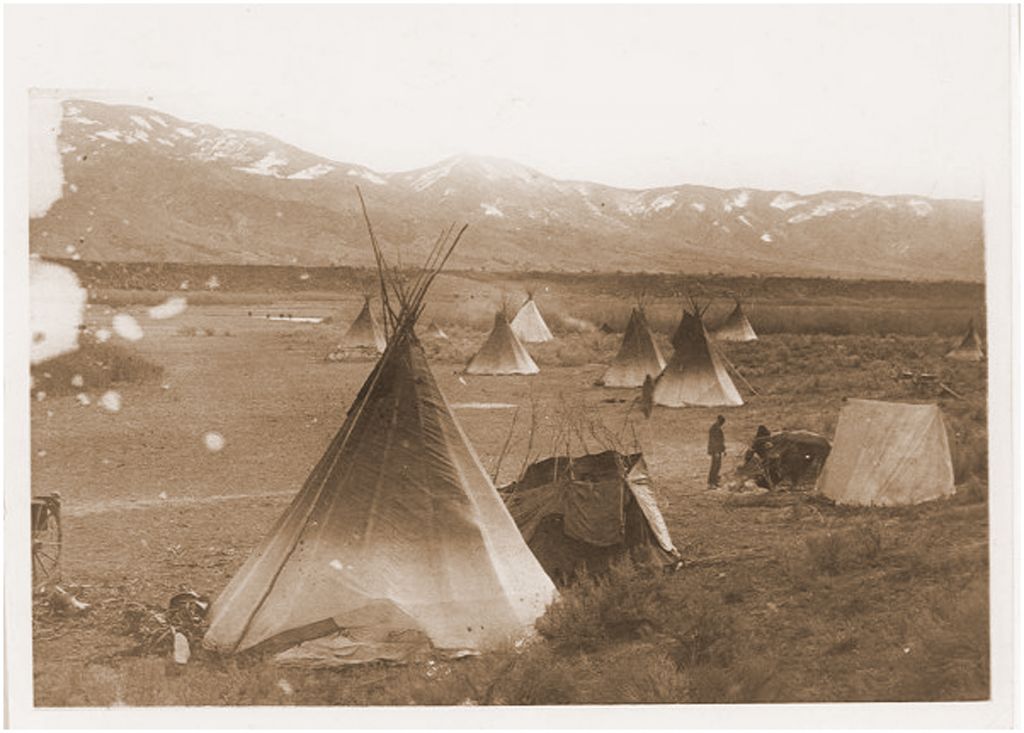

Shoshone and Bannock tipis before Pocatello, Idaho was established, near present-day Ross Park with Chinese Peak visible in background, 1882, Photo courtesy of Idaho State Historical Society

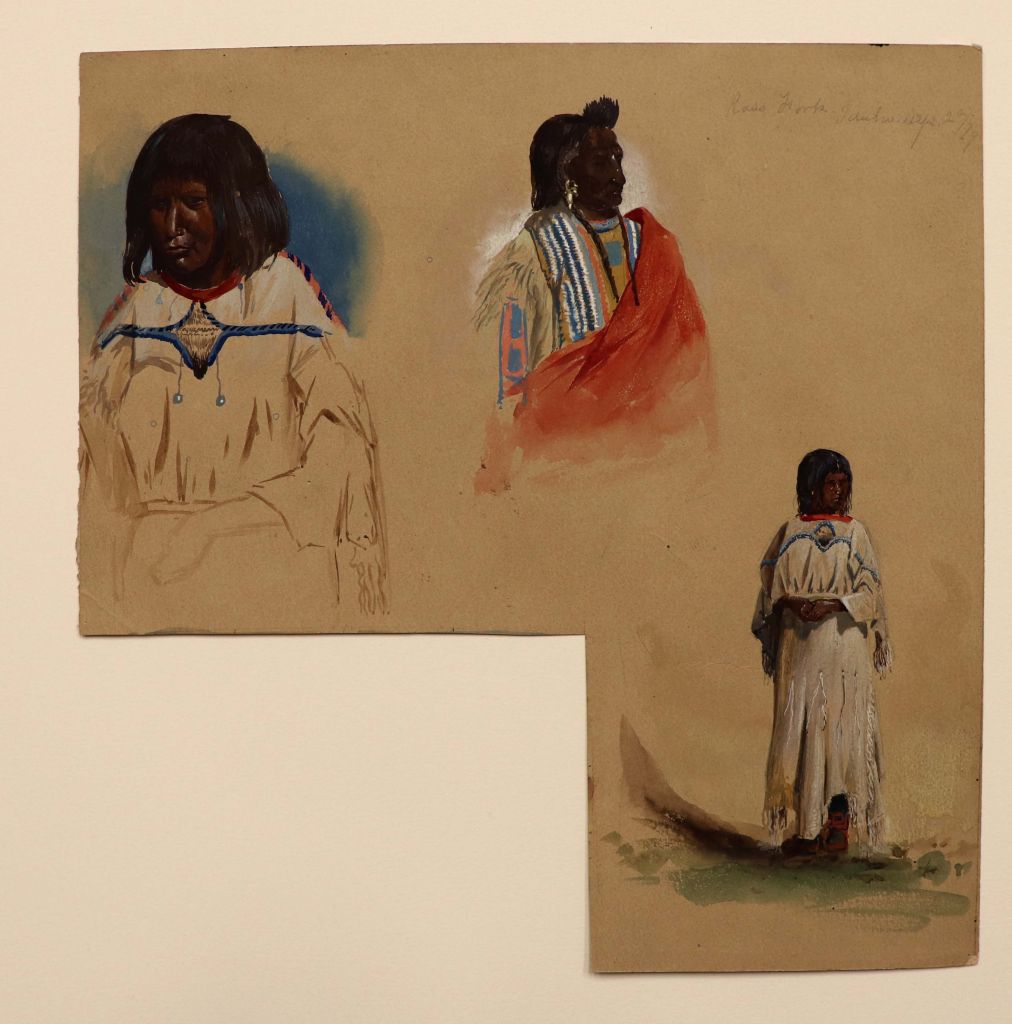

There is a closely related drawing to the painting’s composition but its location is unknown today. It was last sold at auction in 1998. The drawing bears the inscription, “Ross Fork, Idaho,” which is a tributary stream of the Snake River located at the site of the reservation. There are also a small group of sketches that Peter made while at the reservation located today in the Roswell Museum and Art Center, Roswell, New Mexico. They include five studies of Bannock in their traditional dress. The prominent red cloak worn by the central figure is most likely a Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) wool blanket. These were often traded to Indigenous people for beaver pelts.

Peter Moran, Three Indians, Ross Fork Idaho, 1879, watercolor on paper, Gift of Senator Clinton P. Anderson, Roswell Museum and Art Center

Given everything we have found about the work:

· The structures

· The clothing

· The red wool HBC blanket

· The figures that correspond to the drawings at the Roswell Museum

· The numerous ponies in the painting

· The actions of the central figure

· Knowing that the related drawing is inscribed “Ross Fork Idaho”

It is clear that Indian Encampment is actually a faithful representation of a group of Bannock near Fort Hall, made following the Moran brothers’ trip to the Tetons in early September, 1879.

The museum will continue to work towards confirming the identity of our Peter Moran painting as Bannock Indians Breaking a Pony. This discovery is just one example that demonstrates the power of taking the time to slow down and really observe what you’re looking at. The next time you find yourself looking at an artwork, whether it’s a painting you’ve seen a hundred times or are encountering for the first time, we invite you to pause and look deeply. You may notice something new!

[1] Anne Morand, Thomas Moran: The Field Sketches 1856-1923 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996)

[2] Shoshone-Bannock Tribes | Located on the Fort Hall Indian Reservation (sbtribes.com), www.sbtribes.com

[3] National Geographic, “The People of the Horse,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VKi-8K_7xwo&feature=emb_logo

[…] depiction of Native Americans in this gallery is the Peter Moran painting Indian Encampment. It depicts the Bannock Indians who had settled on reservation lands in Southern Idaho just over a de…. Gilbert Gaul and Peter Moran, both displayed in this exhibit, served as special agents in 1890 for […]