Continuing exploration of our current exhibit, another studied theme centers around the Bison and the Plains Indian. One gallery wall of artworks features the chaos and movement during the actual hunt. Opposite that wall is a progression of paintings highlighting Plains Indian women and their role in relation to moving camp during hunting season created by Charles Russell from early in his career into the 1910s, representing a 20-year span of the artists treatment of this theme.

Seeking New Hunting Grounds (Breaking Camp; Indian Women and Children On The Trail) | Charles M. Russell | c. 1891 | Oil on canvas | 23.75 x 35.875 inches

Bringing Up the Trail | Charles M. Russell | 1895 | Oil on canvas | 22.875 x 35 inches

Charles Russell’s Paintings

Close Up of Seeking New Hunting Grounds

During buffalo hunt expeditions, while the men would ride ahead and guard the flanks, the women moved their children and other possessions such as the lodge coverings on tipi-pole travois behind their horses, as shown in Seeking New Hunting Grounds, ca. 1891. This painting is all about the generational family unit, from the women, both older and younger with their children, to the mare and her young colt trailing downhill, to the domesticated wolf-dog with its puppies riding alongside in the cook pot as part of the travois bundle. The generational family unit is a theme that Russell returns to later at the height of his powers as a painter and colorist, as seen in Russell’s 1911 In the Wake of the Buffalo Runners.

Following in the wake of the hunt, darkness is falling in Russell’s 1895 Bringing Up the Trail as the women and children bringing up the rear are anxiously scanning the horizon for sign of the men. Their concern is expressed in the central woman’s posture, the look on the face of the boy watering his horse, and by the dog’s alert stance.

We reach the conclusion of the hunt in Russell’s 1901 Returning to Camp, at which time it was traditionally the women’s role to process the bison, turning it into food, clothing and shelter. Here the hunters have ridden ahead, leaving the women and boys to transport the spoils of the chase back to the village by travois or on the back of pack horses.

Returning to Camp | Charles M. Russell | 1901 | Oil on canvas | 24.125 x 36 inches

Charles M. Russell, In the Wake of the Buffalo Runners, 1911, Oil on canvas, Private Collection

The Blackfeet Indians

Many of the women depicted in these paintings are likely Blackfeet Indians. Historically, in the U.S., the Blackfeet lived in the upper Great Plains north of the Missouri River and east of the Rocky Mountains.[1] Much of that area is now the state of Montana. The Blackfeet (or Amskapi Pikuni) are part of the Blackfoot Confederacy, which is the collective name for the four bands that make up the Blackfeet (or Blackfoot) people. Three of the four bands live in Canada. Earlier in his career, in 1887-1888, scholars believe Russell spent time near Alberta, Canada living among the Blood Indians, a band of the Blackfeet. It was during this period that the artist received his Blackfoot name, “Ah-Wah-Cous.” Like Russell, another artist in the museum’s collection who also developed a relationship with the Blackfeet is Edwin W. Deming. In 1913, Deming and his family attended the Blackfeet Sun Dance in Glacier National Park – an event that brought together the Blackfeet Confederation. Deming was adopted into the tribe and was granted the name “Eight Bears” from the Blackfeet member Running Antelope.[2]

The Roles of Women

Among the first written records of the Blackfeet Indians were the journals of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, who contacted the tribe in about 1806. Unfortunately, those descriptions largely misrepresented Blackfeet women. “As Western men, they only saw what they wanted to see—women with less virtue,” said Susan Webber, a Montana state representative who also teaches Indian women’s studies and philosophy at Blackfeet Community College. Traditionally, Blackfeet women owned their homes and were subservient to no one. “Our role was always ‘sits beside him,’ not ‘sits behind him’ or ‘walks three paces behind him.’ In our ways, women are men’s greatest support and greatest weapon,” says Webber.[3] What early explorers and anthropologist often failed to recognize was the balance of power that existed between genders in Native American communities like the Blackfeet.

Buffalo hunts demonstrate this interdependence between genders. For the Blackfeet, the women depended on the men to hunt the bison while the men depended on the women to process and transform the buffalo hides. After butchering the animal, the women then had to prepare the buffalo hides for its many uses, such as constructing the tipi. Tanning hides is an arduous process – each buffalo hide took two full days of work to prepare, though some parts took longer such as drying the hide in the sun. A woman of average skill was said to be able to tan as many as 25 hides in a season.[4] One tipi could require up to 12 to 14 buffalo hides. Erecting the tipi itself was no small feat, either. A tipi cover weighed close to 100 lbs. The wooden poles (as seen in the travois of Russell’s paintings discussed previously) were typically 18 to 20 feet long each. The average tipi was 14 to 16 feet in diameter and stood about 17 feet tall on average.[5]

Lakota Parfleche Displayed at the National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, D.C.

In the days when leather was a basic article of daily life for the Blackfeet, a woman was judged by her tanning skills. The first stage of tanning turns a fresh hide into rawhide, which was a useful material for many purposes, the most common of which was as storage containers. These rawhide containers were known as parfleches. A parfleche is made of a solid piece of rawhide, folded like an envelope. Some parfleches were used to hold dried food, which when properly folded and tied with strings, were typically safe from mice and bugs. Other uses for rawhide containers included making square or cylindrical bags to hold sacred objects or headdresses and special clothing, or transforming rawhide into saddle bags for transporting. And of course, rawhide was used to make moccasin soles, drumheads, and rattles.[6]

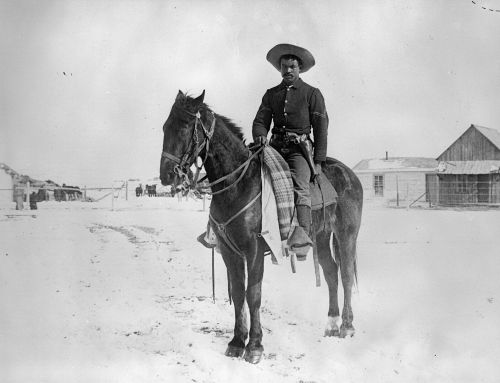

Salish mother. Photographed by Edward S. Curtis, circa 1910. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

The Blackfeet woman’s role was intricate, working hard not only in preparing shelter, food, and tools, but also in raising and caring for the children. In Seeking New Hunting Grounds, the central figure rides with her children, her toddler wrapped in a blanket in front while her infant is carried on her back in a cradle board. Historically, Blackfeet mothers made the cradle board frames out of willow branches, and later out of large boards cut to their desired shape. They then covered the board with fitted pieces of buckskin laced with an oblong bag in which to place the baby. Often cradle boards were lined with fur or moss. Some mothers attached long strands of beads or shells hanging to amuse the baby with their movement and sounds.[7]

The Power of Blackfeet Women

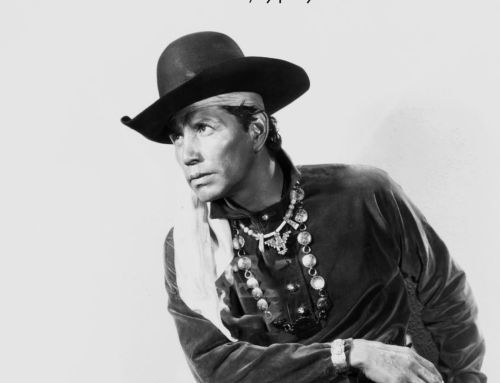

Running Eagle (or Pi’tamaka)

One of the most famous Blackfeet women was Running Eagle (or Pi’tamaka), also known as “Brown Weasel Woman.” She was born into the Piikáni Piegan Tribe of the Blackfeet Nation. Running Eagle’s father was an important warrior, and she learned from him how to hunt and fight. She eventually became a war chief of her tribe, and was known for her success in battle. Today, the Pitamakan Lake in Glacier National Park, Montana is named after her.[8]

Like Running Eagle, who serves as a role model for young women today, a new generation of Blackfeet girls are learning how to fight. In 2003, Frank Kipp founded and opened Blackfeet Nation Boxing Club on the Blackfeet Reservation in Browning, Montana. Kipp started the club to help keep young adults out of trouble, and over time, the space became a refuge for young women. Kipp taught these girls how to protect and defend themselves.[9] According to the Justice Department, Native American women are more than 10 times more likely to be murdered than non-Native women. Studies reveal that 1 in 3 American Indian women will, at some point in her life, experience sexual violence.[10] People like Kipp and his boxing club are trying to change that statistic. Kipp’s daughter, Donna Kipp, recalls, “When I started boxing, I remember watching the older girls train at the club and viewing them as role models. They were not just boxers but fighters. All of those older girls embodied strength, the type of strength that we’d hear in stories about our ancestors.”[11] Blackfeet ancestors like Running Eagle.

A traditional Cheyenne saying exemplifies the intrinsic role that women played in the well-being of Native American cultures like that of the Blackfeet peoples:

A nation is not conquered

Until the hearts of its women

Are on the ground.

Then it is done, no matter

How brave its warriors

Nor how strong its weapons.[12]

[1] William Farr, The Reservation Blackfeet (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1984), p. 4.

[2] Thomas G. Lamb, Eight Bears: A Biography of E.W. Deming, 1860-1942 (Oklahoma City, OK, 1978): 75-78.

[3] Alysa Landry, “The Power of Blackfeet Women,” September 13, 2018, Indian Country Today, https://indiancountrytoday.com/archive/power-blackfeet-women

[4] John C. Ewers, The Blackfeet (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1958), pp 109-110.

[5] Barbara Oldershaw, “Blackfeet American Indian Women: Builders of the Tribe,” Places, Volume 4, Number 1, p. 41-44. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0s58p2fc

[6] Beverly Hungry Wolf, The Ways of my Grandmothers (New York: Harper, 1980), p. 213-214.

[7] Hungry Wolf, p. 247-248.

[8] “Pi’tamaka (Running Eagle),” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/people/pi-tamaka-running-eagle.htm

[9] Donna Kipp, “How the Blackfeet Nation Boxing Club is fighting to save the lives of Native American women,” ESPN, June 30, 2020, https://www.espn.com/boxing/story/_/id/29383248/blackfeet-nation-boxing-club-fighting-save-lives-native-american-women.

[10] “Protecting Native American and Alaskan Native Women From Violence: November is Native American Heritage Month,” The United States Department of Justice Archives, November 29, 2012, https://www.justice.gov/archives/ovw/blog/protecting-native-american-and-alaska-native-women-violence-november-native-american

[11] Donna Kipp, “How the Blackfeet Nation Boxing Club is fighting to save the lives of Native American women,” ESPN, June 30, 2020, https://www.espn.com/boxing/story/_/id/29383248/blackfeet-nation-boxing-club-fighting-save-lives-native-american-women.

[12] Gretchen Bataille and Kathleen Muller Sands, American Indian Women: Telling Their Lives (New York: The Dial Press, 1974), p. vi.

Thank you so much for this brief but intimate look into the roles of Blackfeet women.