“Few who would acquire a knowledge of the heavens, let him give up his days and nights to the marvels of Orion.” – Charles Edward Barns, a writer and hobby astronomer of the late 19th century

Frederic Remington completed over 70 compositions of night scenes from 1900 until his death in 1909. The artist referred to these paintings as his moonlights, and today we refer to them as nocturnes. The Sid Richardson Museum has 5 nocturnes in its collection. Our current show, Night & Day: Frederic Remington’s Final Decade, features 10 of Remington’s night paintings. Nocturnal images were crucial to Remington because he saw them as key factors by which to be considered as a fine art painter by his peers and critics, moving beyond his reputation as an illustrator. Spoiler alert: it worked.

But Remington was not the first to capture the night sky. Night scenes were prolific in the Romantic movement of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Focused less on observation, these canvases exemplified feeling, mood, and imagination. Later in the 19th century, a special group of the Hudson River Valley School artists focused on the effects of moonlight in their artworks, sometimes tranquil, sometimes dramatic. By the 1880s, the art world was introduced to a group of painters known as the Tonalists. Again, these artists explored the delicate effects of light to creative suggestive moods, but were also interested in a style of painting that was limited in color scale as well.

Charles Rollo Peters (American, 1862–1928), San Fernando Mission, n.d. 24 x 16 inches. Crocker Art Museum, gift of William C. Wright, conserved with funds provided by the Historical Collections Council of California Art, 1962.23

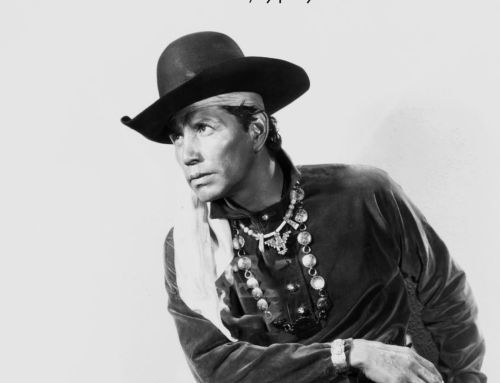

Frederic Remington | Apache Medicine Song | 1908 | Oil on canvas | 27.125 x 29.875 inches

Remington was familiar with Tonalism, particularly the work of Charles Rollo Peters, who was highly regarded for his night time paintings in the late 19th century. Remington saw Peters’ work at a show in New York in 1899, after which Remington begins his own nocturne series the following year. Look at the background of Remington’s 1908 Apache Medicine Song. The building, the trees, the sky – they are painted in a Tonalist manner. Notice the two sources of light in this composition: the campfire and the moonlight, the evidence of which is seen by the shadows cast on the ground. Where Remington differs from the Tonalist is that he never fully separates himself from a narrative. Remington can’t seem to leave the story behind, even if it’s an incomplete story as seen in his 1906 A Taint on the Wind, in which the cause of the spook is unknown, beyond the frame of the canvas.

Frederic Remington | A Taint on the Wind | 1906 | Oil on canvas | 27.125 x 40 inches

Around this same time, American Impressionists were capturing contemporary, everyday scenes, including night scenes. In these cityscapes set at night, a 21st-century viewer might overlook the inclusion of street lamps. But it’s important to note that electricity was becoming commonplace by the late 19th century, and with this new technology, changing the urban landscape and how one experienced night time in the city.

Likewise, how one studied and understood the night sky was changing in the latter half of the 19th century in Remington’s lifetime. Astronomy is made up of two branches: observers and theorists. Observers try to use the latest technology to capture the night sky, while the theorists try to explain what it is that we’re seeing. In the late 19th century, scientists were trying to figure things out like the basic size of the solar system, how far away from the sun is Earth, or how old the Earth is. What helped these studies is that, by Remington’s time period, there were growing advances in both photography and spectroscopy, or the study of color from visible light to all bands of the electromagnetic spectrum. Why is that important? Well, studying the spectra of the items found in the night sky – like a nebula, a comet, a star – can tell scientists what elements make up that object. Additionally, in the late 19th century, photographers began to point their cameras up to the night sky via telescopes, which were also improving in efficacy. One observer, Andrew Common, captured in a photograph in an 1883 photograph. This is the first time people saw stars on a photograph not visible to the naked eye.

Andrew Common, Photograph of Orion Nebula, 1883, public domain

You can learn more about the astronomical discoveries of Remington’s time period in a recorded pair lecture program about the study of night in art and space. TCU art history professor Dr. Mark Thistlethwaite situates Remington’s nocturnes within the practice of late 19th century American art. Dr. Doug Ingram, senior instructor from TCU Department of Physics & Astronomy, follows with an examination of the study, views, and beliefs of the night sky at the turn of the century.

Leave A Comment