NIGHT & DAY: FREDERIC REMINGTON’S FINAL DECADE

September 24, 2022 – April 30, 2023

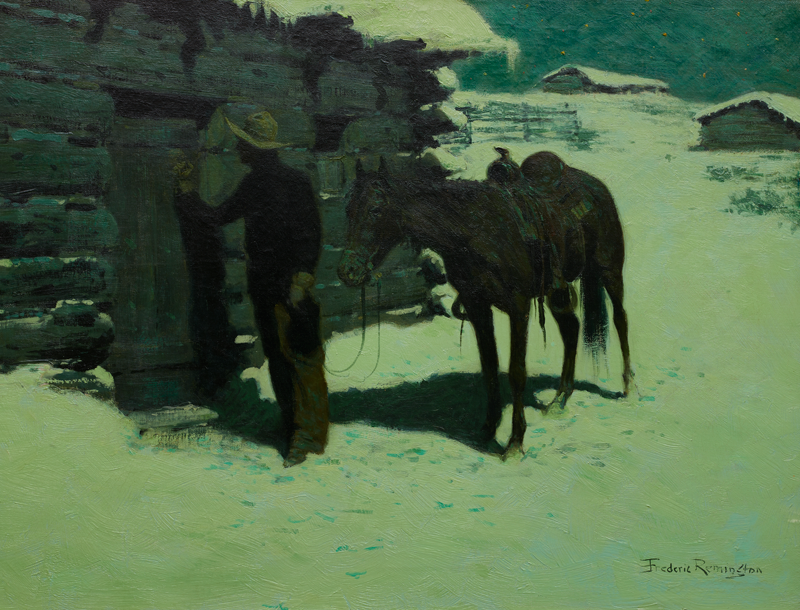

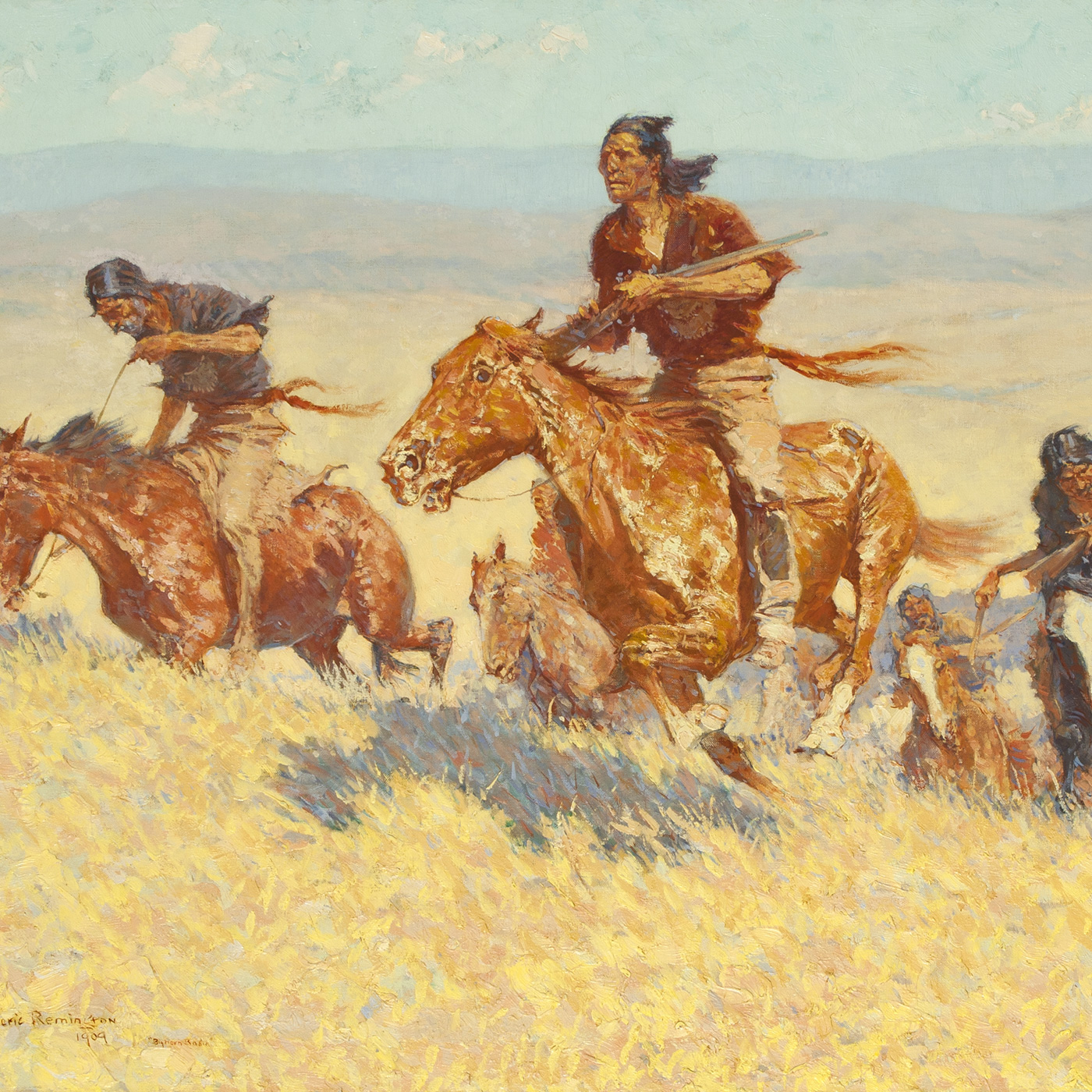

This exhibition explores works made in the final decade of Frederic Remington’s life, when the artist alternated his canvases between the color dominant palettes of blue-green and yellow-orange. The works included range from 1900 to 1909, the year that Remington’s life was cut short by complications due to appendicitis at the young age of forty eight. In these final years Remington was working to distance himself from his long-established reputation as an illustrator, to become accepted by the New York art world as a fine artist, as he embraced the painting style of the American Impressionists. In these late works he strove to revise his color palette, compositional structure, and brushwork as he set his Western subjects under an interchanging backdrop of the shadows of night and the dazzling light of day.

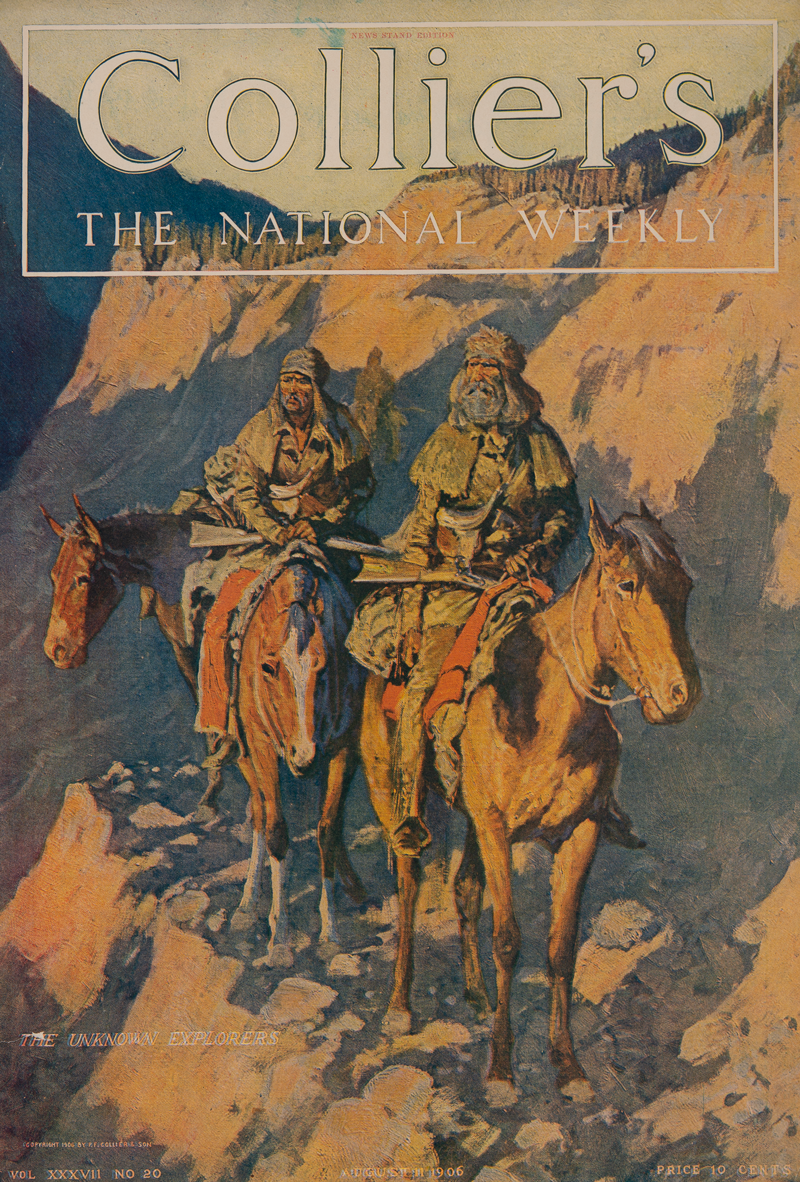

Throughout his career Remington revised and reworked compositions across media, from his illustrations to his oils to his three-dimensional bronzes. As part of this process of revision, Remington took extreme measures from 1907 to 1909 when, as part of his campaign toward changing the perception of his art, he destroyed well over one hundred works that he felt did not satisfy his new standards of painting. On one such occasion, the evening of January 25, 1908, he burned around thirty canvases. He wrote in his diary, “They will never confront me in the future – tho’ God knows I have let enough go that will.” In the back of the same diary, he listed paintings that he had incinerated and next to three of them, he noted “redone, 1908.” A contract made with Collier’s magazine that began in 1903 meant that many of the works he destroyed are preserved through halftone reproductions published by that journal. The inclusion of these images in this exhibition offers the opportunity to compare them with modified and remade compositions Remington produced in his final years.

EXHIBITION ESSAY

NIGHT & DAY: FREDERIC REMINGTON’S FINAL DECADE

By Dr. Mark Thistlethwaite

“All who are interested in the best in American art will deplore the taking off of the artist, Frederic Remington, while yet in his prime.” This sentence opened the artist’s obituary published in the Fort Worth Record of December 31, 1909.[1] Remington’s admirers across the nation were stunned to learn of his sudden death from complications following an appendectomy. Just forty-eight years old, Remington was not only in his prime, but also at a critical juncture in his career. During his final decade he continued to be enormously prolific in the quantity of art he produced, but he also challenged himself to improve the quality of his oil paintings to gain respect as a fine art painter rather than an illustrator. The distinction between the two being that illustrators depended on a text, generally worked at a small scale, and typically in black and white, while fine art painters drew upon their imaginations, usually constructed larger, more complex compositions, and manipulated light, color, and brushwork in nuanced and expressive ways. To understand how Remington met the challenge of transforming his art, this exhibition brings together a selection of his final decade paintings that focus on his fascination with capturing the light and color of the West under both blazing sun and cool moonlight.

Remington’s effort to elevate himself to the status of fine art painter was bolstered by a lucrative contract with Collier’s Weekly (known as Collier’s after 1905). This widely-circulated national magazine commissioned Remington to produce twelve oil paintings a year, from 1903 to 1908, on subjects of his choice to be reproduced as single- or double-page color halftones. Remington now had the artistic freedom and financial means to move from illustrations based on specific texts to paintings of his imaginings. Collier’s also published numerous individual and sets of reproductive prints of the artist’s paintings, which the journal advertised heavily in its issues. The association with Collier’s proved historically important because it published color reproductions of several paintings that no longer exist; Remington in 1907 burned seventy-five of his paintings and “a lot of old canvases” in 1908.[2] Some of these compositions are only known now through Collier’s reproductions. Such destruction seems incredible, but Remington’s aim was to cull artworks that would not enhance his goal of being recognized as a serious artist. Sometimes Remington repainted the subjects of the destroyed works, including The Unknown Explorers, which he revised in composition and style.

Even though The Unknown Explorers was a late painting (from around 1905 and published as Collier’s cover in 1906), it still displayed the attention to detail from which Remington was moving away. He redid the subject in 1908 by muting the detailing of the figures and landscape with a dusty atmosphere and by strikingly juxtaposing pared-down areas bathed in radiant sunlight with other areas presented as aqueous shadows. This second version of The Unknown Explorers reveals the impact Impressionism had on Remington as he strived to gain critical acclaim by modernizing his style.

Frederic Remington likely encountered Impressionist artworks in 1886 when studying at the Art Students League in New York City. He was there when the city’s first major exhibition of French Impressionism opened. Although the last Impressionism exhibition in Paris occurred also in 1886, for most Americans the art on view in Manhattan was regarded as modern and radical: the Brooklyn Eagle of April 11, 1886 summarized the exhibition as “The funniest performance to be seen in New York” and criticized the works’ weak drawing and preposterous color by concluding that the “impressions” are by those who have been taking liquor or opium.[3] As late as 1909 when asked what he thought of Impressionist paintings, a New York newspaper quoted Remington as replying: “I’ve got two maiden aunts in New Rochelle that can knit better pictures than those!”[4] Remington was being facetious, perhaps to deflect any hint of foreign influence on what many contemporaries deemed his distinctly American art. For throughout his final decade, Remington was not only friends with several American Impressionists, but he also increasingly adopted the quick dabs of paint and coloristic dynamics of Impressionism, as well as its practice of painting sketches outdoors. Remington noted in his diary on January 16, 1908: “By gad a fellow has got to trace to keep up now days – the pace is fast. Small canvass [sic] are best – all plein air [outdoor] color and outlines lost – hard outlines are the bane of old painters.”[5] By incorporating qualities of Impressionism into his compositions Remington could be perceived as more artistically modern and viewed more favorably by art critics.

And this did occur, for instance, in the comprehensive review of Remington’s art written by Giles Edgerton [pseudonym of Mary Fanton Roberts] for the March 1909 issue of The Craftsman magazine. Remington declared it: “the only intelligent art article about myself ever written.”[6] The writer was captivated by Remington’s “most extraordinary variation” in his handling of light in his late pictures, which she attributed to “the one influence which Remington acknowledges frankly”—Claude Monet.[7] While their art differed in many ways, both artists regarded light as “the” essential compositional element and aspired to express its nuances and its affect on color in their paintings. Edgerton extolled Remington’s latest canvases:

In one, a harsh bronze light glittered over parched prairies and alkaline waters; in another there was the silver radiance of a sparkling winter high noon; again, the tender ineffable light of a gray-green early night with stars glistening through the thick soft atmosphere. . . almost always in Remington’s more recent pictures [you] look first for the light over the canvas, not for the detail or the color or the outline . . .[8]

The art writer’s praise for Remington’s success in conveying the effects of light in both his daytime and nighttime paintings is significant because along with Remington’s adoption of an impressionistic style in his effort to gain fine art credibility was his integration of nocturnal images into his pictorial repertoire.

Owing to the renown of American expatriate painter James Abbott McNeill Whistler’s “nocturnes” and the American art movement known as Tonalism, nighttime scenes enjoyed a resurgence in the late nineteenth century. After viewing an 1899 exhibition in New York of night paintings by the California Tonalist artist Charles Rollo Peters, Remington seems to have been inspired to produce what he called “moonlights.” During his final decade, Remington completed over seventy of these nighttime compositions. As in his daytime paintings, Remington applied Impressionism-based quick touches of colors to his moonlight canvases. Also like daylight compositions, his moonlights derived from sketches he would do outdoors (usually when he summered at his island retreat in the St. Lawrence River). As Remington had hoped, his moonlights did contribute significantly to gaining respect as a fine artist. When A Taint on the Wind was first shown in 1906 at New York’s M. Knoedler & Co. gallery, art critics declared it to be “the most important” painting on view.[9] One critic praised it as a “painter’s picture,” while another writer asserted that this entire 1906 group of eleven new oil paintings of night and day scenes, “proves in and by them that he is now a painter and not solely an illustrator.”[10]

In Frederic Remington’s last years, art writers acknowledged and admired his development from illustrator to fine artist. He must have been deeply satisfied when he wrote in his diary that: “My [December 1908] show at Knoedler’s closes tonight. It was a triumph. I have landed among the painters and well up too.”[11] A year later he wrote of his annual Knoedler’s exhibition: “Splendid notices from all the papers. They ungrudgingly give me a high place as a ‘mere painter.’ I have been on their trail a long while . . . . The ‘illustrator’ phase has become background.”[12] Just over two weeks after writing this diary entry, the artist died. The New-York Tribune lamented Remington’s passing while confirming that he had achieved “new powers as a painter,” which the newspaper’s critic credited to Remington’s “enthusiasm for the medium he employs.”[13] That enthusiasm and Frederic Remington’s success in securing fine artist stature are abundantly clear in the artworks on view in Night & Day: Frederic Remington’s Final Decade.

Mark Thistlethwaite, Professor of Art History Emeritus, Texas Christian University

ENDNOTES

[1] “Remington’s Work,” Fort Worth Record, December 31, 1909.

[2] Frederic Remington Diary, January 25, 1908, Frederic Remington Art Museum, Ogdensburg, New York.

[3] “Gallery and Studio. A Curious Exhibition in the American Art Gallery,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 11, 1886.

[4] “Wooly Art,” Watertown Herald, June 12, 1909.

[5] Frederic Remington Diary, January 16, 1908, Frederic Remington Art Museum, Ogdensburg, New York.

[6] Remington Diary, February 28, 1909.

[7] Giles Edgerton [Mary Fanton Roberts], “Frederic Remington, Painter and Sculptor: A Pioneer in Distinctive American Art,” The Craftsman 17, no. 6 (March 1909): 669.

[8] Edgerton, 669.

[9] “Art and Artists. Remington Indian Pictures at Knoedler’s—Notes,” New York Globe and World Advertiser, December 19, 1906; “Exhibitions Now On,” American Art News 5, no. 1 (December 22, 1906): 6.

[10] “Art and Artists. Remington Indian Pictures at Knoedler’s—Notes”; “Exhibitions Now On.”

[11] Frederic Remington Diary, December 12, 1908, Frederic Remington Art Museum, Ogdensburg, New York.

[12] Remington Diary, December 9, 1909.

[13] “Frederic Remington,” New-York Tribune, December 28, 1909.

#MuseumFromHome

Night & Day: Frederic Remington’s Final Decade

Ride along with the risk-takers and romantics of the American West captured on canvas and brought to life in vivid detail. This 360-degree exploration delves into the artists who captured the American frontier in paint and bronze through this exceptional collection of artworks by premiere Western artists. Immerse yourself in Frederic Remington’s Western subjects set under the shadows of night and the dazzling light of day.