Our new exhibit, Charles M. Russell: Storyteller Across Media, focuses on the artist’s talent and ability to tell stories through his art. He communicates his stories through paint, canvas, paper, bronze, and any other material he could find. In the case of one story featured in the exhibit, he retold it through a few different media and compositions.

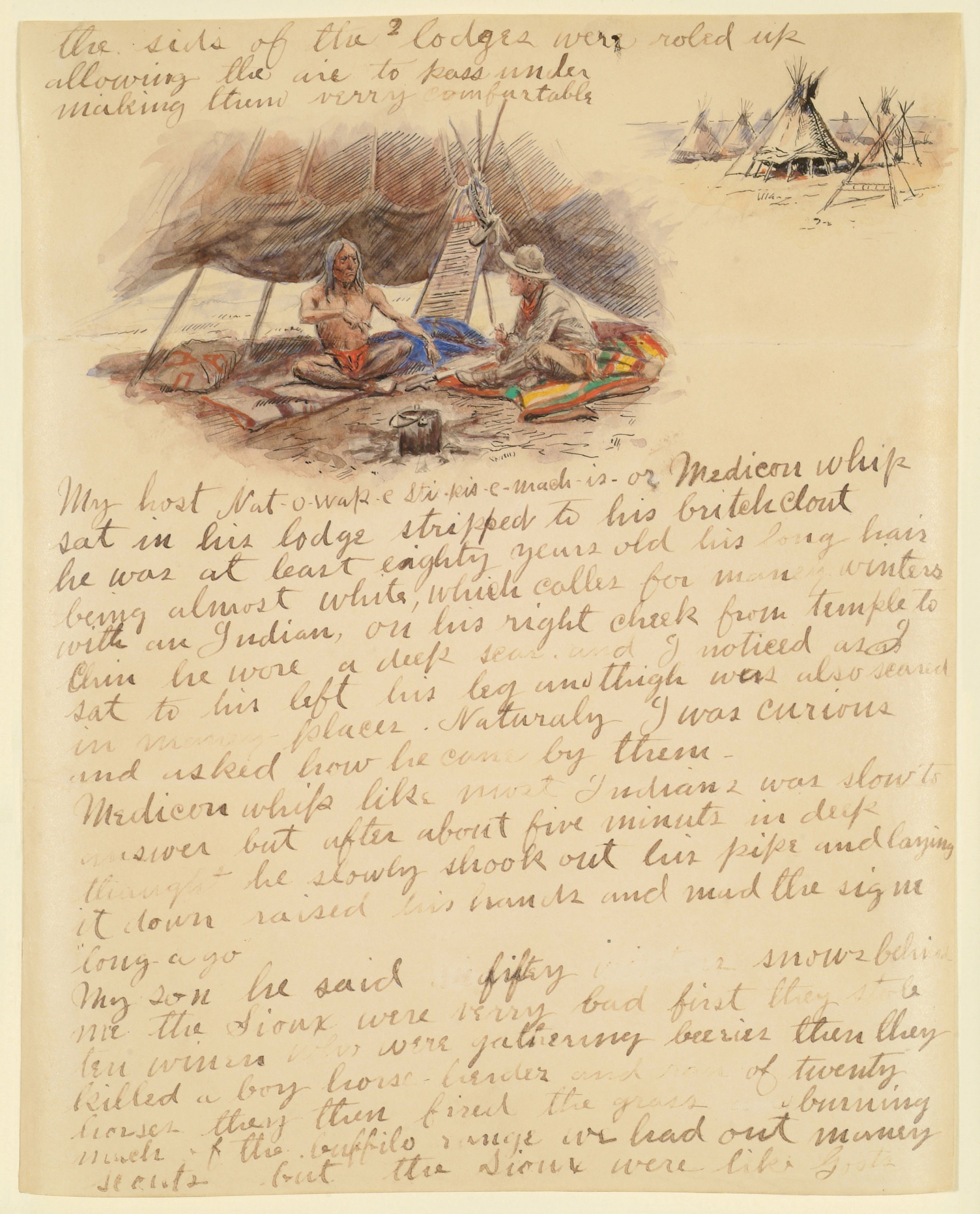

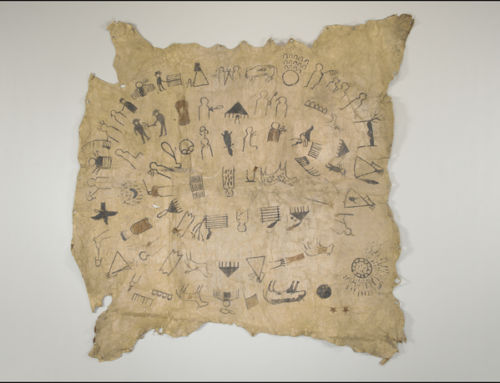

Near the entrance of the exhibition, visitors will encounter a grouping of works related to an event called counting coup. To count coup was a high honor among Plains Indians, and often consisted of touching the enemy with a club or whip without causing harm, though there were various levels of counting coup, including killing an enemy or being wounded during close combat. The narrative Russell recounts is one that was told to him by Medicine Whip, a Blood warrior (a band of the Blackfoot Confederacy). In 1902, Russell wrote a 5-page, illustrated letter to St. Louis patron George W. Kerr, based on Medicine Whip’s story. The artist pictures himself listening to Medicine Whip as he told Russell about a battle “fifty snows ago,” in which Medicine Whip and his fellow Blood Indians fought the Sioux [the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ]. Russell tries to retell Kerr the tale as it was told to him:

Charles M. Russell, Letter from Charles M. Russell to George W. Kerr, September 29, 1902, pen & ink, pencil, watercolor, and gouache on paper, Private Collection

“…it was not long till maney Bloods were on their war poneys in the track of the Sioux the sun was not yet in the middle when we sighted them. It was a running fight until we killed the horse of their medicine man then his braves gathered about him and faught so strong we could not reach them our arrows were nearly all gone, the Sioux had been wise and saved theirs.”

Medicine Whip had counted three coups against the Sioux [the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ] that day. Russell documented Medicine Whip’s valor in visual narrative with his 1902 painting Counting Coup. The canvas reflects the tones of “a pale, grayish pearl,” as his wife and manager, Nancy, once noted, colors that are in striking contrast to the violence on display in this scene. Russell brings the story into three dimensions with his 1905 bronze Counting Coup. In this sculpture, the original scene from the painting is pared down to its central characters as the warrior who is counting coup lunges with his spear (which counts as a coup of close-quarters combat), while using his shield to fend off a second enemy coming up on his left. Having honed in on the main action of the story, Russell reimagines the story in oil with his 1908 painting When Blackfeet and Sioux Meet, wherein our attention is on the battle between the three warriors.

Charles M. Russell | Counting Coup (Medicine Whip) | 1902 | Oil on canvas | 18.125 x 30.125 inches

Charles M. Russell, Counting Coup, 1905, Roman Bronze Works, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, Amon G. Carter Collection, 1961.116

Charles M. Russell, When Blackfeet and Sioux Meet, 1908, Oil on canvas, 20 1/2 x 29 7/8 inches

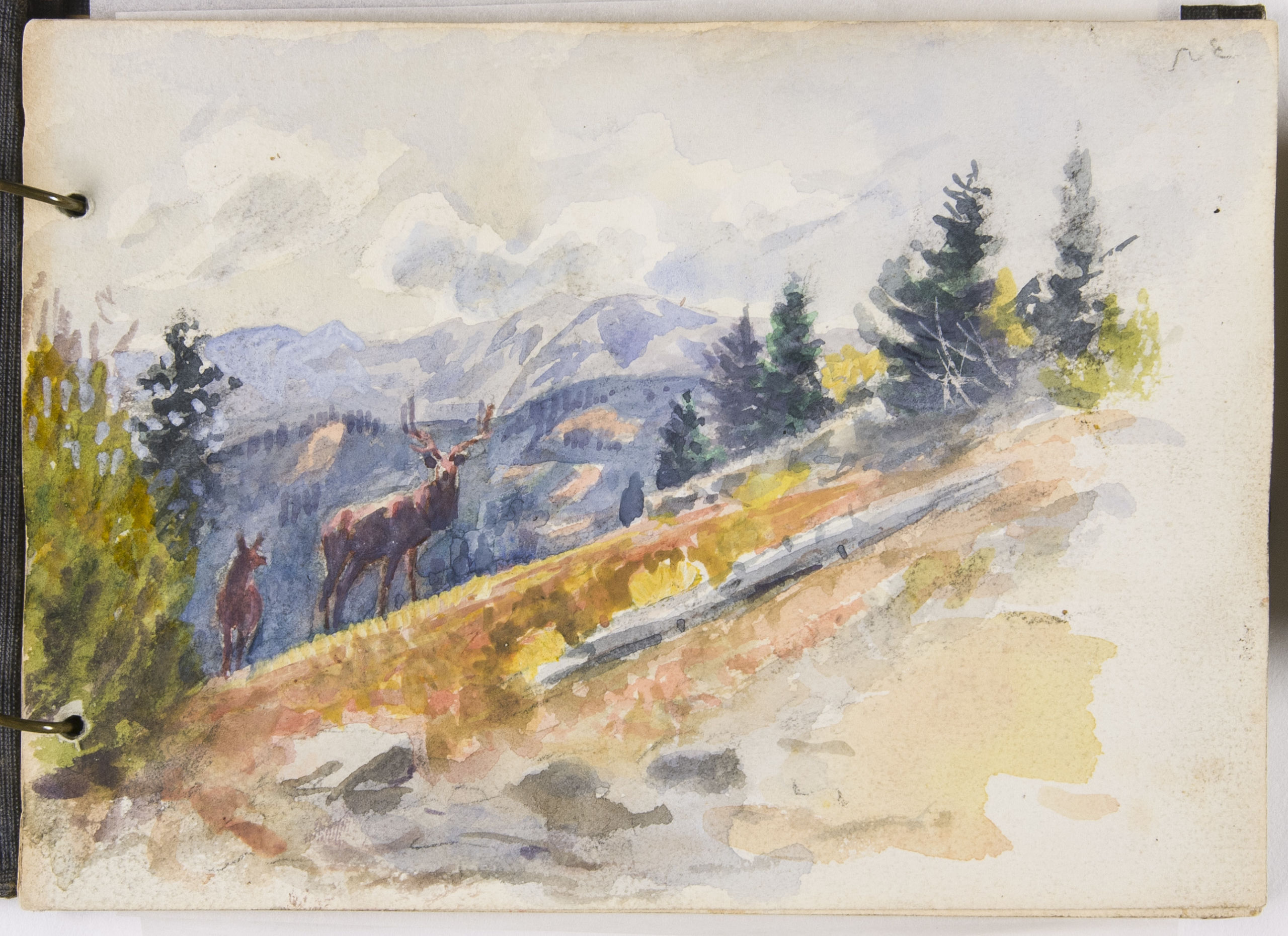

Throughout the exhibit, Russell’s skill in crafting visual narratives is on display. Visitors will get to peak behind the scenes of how Russell worked with a look at one of his sketchbooks from around 1912. This particular sketchbook contains 45 drawings and five watercolors. Some sketches feature wildlife and the natural environment surrounding Russell’s summer cabin at Bull Head Lodge, located in present-day Glacier National Park. Russell would have been able to sketch outdoors with his sketchbook using a sketch box similar to the one on display. Visitors will see the materials Russell kept on hand, like brushes, paint tubes, a paint rag, and his ever-present stash of tobacco and cigarette papers.

Charles M. Russell, [Elk study], ca.1912, Graphite and watercolor on paper, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, Gift of C. R. Smith, 1964.193.1 [part of Russell’s sketchbook]

Charles M. Russell, [Russell’s sketch box], ca.1864-1926, Wood, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, Amon G. Carter Collection, 1961.66

Russell was a skilled watercolorist, and visitors will delight in seeing his watercolor prowess in works like Navajo Trackers. Russell had encountered the Navajo [the Diné] during a 1916 trail ride in Arizona organized by his friend Howard Eaton. The artist took notice of their dress, sharing details of his impression in a letter to his friend, the painter Edward Borein.

“Saddles and concho belts silver and turquoise and year [ear] rings they were all hatless som wore split pants their shirts were Navy ho [Navajo] make but it’s a safe bet we could drop back in there history thay would be shy the shirt … in a mixture of dust and red sun light it made a picture that will not let me forget Arizona.”

Obviously Russell did not forget that experience, inspiring this painting made a decade later set against the Mojave Desert, populated with its yuccas and Joshua Trees. The colors in this watercolor shimmer. Painted in the last year of Russell life, the work exemplifies the artist’s mastery of the medium.

Charles M. Russell, Navajo Trackers, 1926, Watercolor on Paper, Private Collection

Charles Russell was and remains known as a great storyteller. From his early days telling stories around the campfire as a night herder to his practice of illustrating correspondence to close friends, Russell spun yarns from his own experiences and imagination, imbued with color and humor. The popular novelist Mary Roberts Rinehart wrote of her experience with him on a trip through Glacier National Park in 1915, “To repeat one of his stories would be desecration. No one but Charley Russell himself, speaking through his nose, with his magnificent head outlined against the firelight, will ever be able to tell one of his stories.” While one may not be able to experience Russell’s performances today, his imaginative narratives can be viewed through the works made in diverse media on display in this exhibition.

Leave A Comment