As mentioned previously, the museum is closed until September 25, when we reopen with a new exhibition, Take Two: George Catlin Revisits the West. The exhibit will feature 17 paintings from Catlin’s Second Indian Gallery. But wait, who is George Catlin and what are his Indian Galleries?

George Catlin (1796-1872) was a self-taught, self-supporting and self-motivated artist, author, showman, promoter, entrepreneur, and ethnographer. Born in Wilkes-Barre, Pa. and trained in the law, he chose art instead. Having the foresight in the 1830s that American Indian cultures were vanishing, he made it his lifelong mission to create a record of all native life in the Americas for future generations.

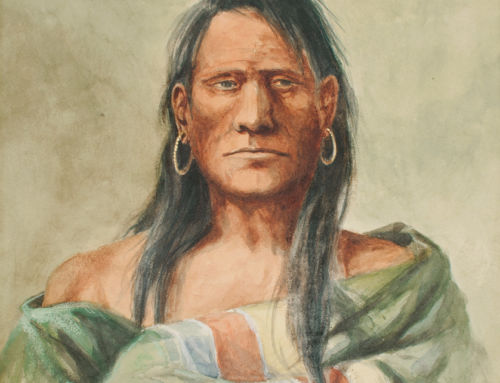

“Buffalo Chase––Bulls Protecting the Calves,” George Catlin (1796-1872), (Cartoon No. 153) Oil on card mounted on paperboard, 18 1/2 x 25 1/16 in., National Gallery of Art, Washington, Paul Mellon Collection

Catlin’s First Indian Gallery

He painted 500 Native American portraits and scenes of everyday life of 48 Indian tribes—buffalo hunts, dances, games, amusements, rituals, and religious ceremonies—that he witnessed on summer excursions in 1832, 1834, 1835, and 1836. The prolific painter was tireless in publicizing his work; he continually sent letters of his travels to be published in newspapers, and he gave lectures showing Indian costumes and artifacts.

He thought his Indian Gallery deserved government patronage. But when he failed to persuade Congress to buy his paintings, Catlin left America at the end of 1839 to find a new audience and new prospects abroad. He would not return until 1871.

Despite the promise of a French king’s commission for Catlin’s La Salle Expedition series, he was unable to find a patron and faced bankruptcy in 1852. Joseph Harrison, a Philadelphia industrialist, paid Catlin’s debts and held the first Indian Gallery as collateral. Catlin was never able to retrieve the Indian Gallery.

Catlin’s Second Indian Gallery

Alleged to have traveled extensively to a number of countries principally in South America from 1854 to 1860, he then settled in Brussels, Belgium. From 1860 to 1870, he completed a second Indian Gallery, which he called the Cartoon Collection. He called these oil paintings “cartoons,” explaining that they were yet unfinished. Relying on his memory of experiences with the American Indians in the 1830s, he drew from images in his first Indian Gallery, adding new subjects from the 1850s to the 1860s. Of the estimated 600 cartoons that he painted, there are 351 in the Mellon Collection, 17 of which are presented in Take Two.

Catlin exhibited the Cartoon Collection in 1870, first in Brussels, then in New York and Washington, D.C., where, in bad health and nearly deaf, he died in 1872.

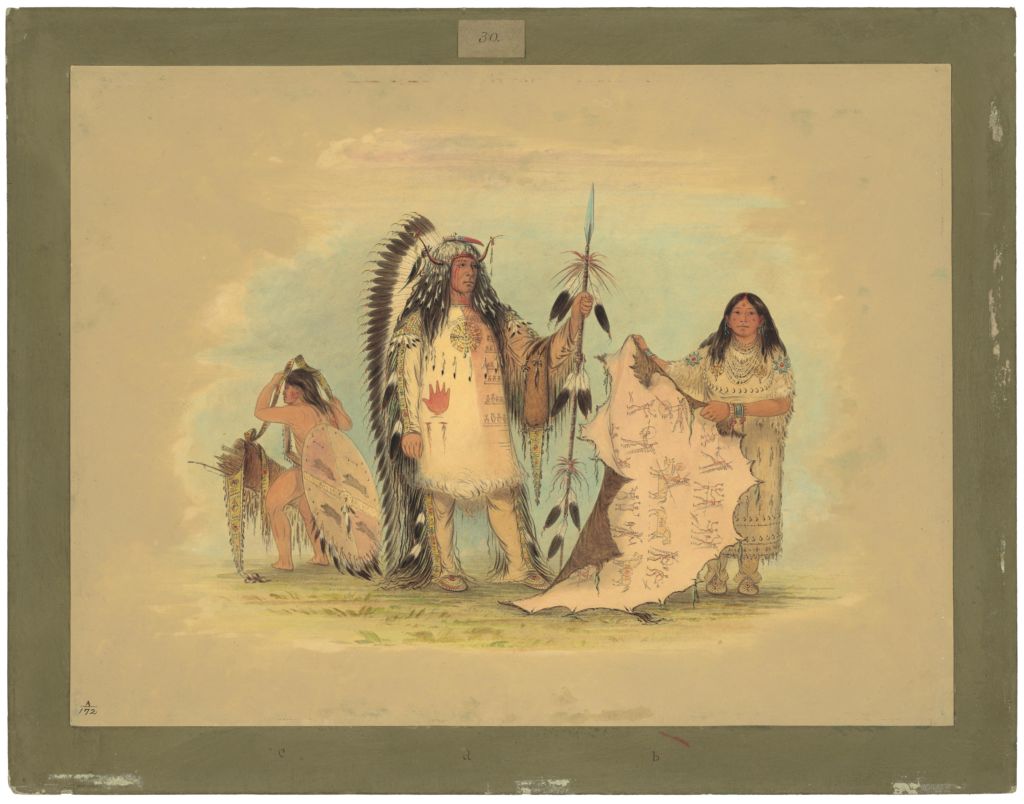

“Mandan War Chief with His Favorite Wife,” George Catlin (1796-1872), (Cartoon No. 30) Oil on card mounted on paperboard, 18 ¼ x 24 5/16 in., National Gallery of Art, Washington, Paul Mellon Collection

Catlin’s Astonishing Visual Legacy

Although Catlin never secured government patronage, his dream of creating a comprehensive visual record of native life in the Americas was nearly fulfilled after his death. In 1879, Joseph Harrison’s widow donated the first Indian Gallery, more than 500 paintings, to the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. In 1912, Catlin’s heirs sold the Cartoon Collection to the American Museum of Natural History in New York. In 1965, the late Paul Mellon, philanthropist and board member of the National Gallery of Art, purchased works in the Cartoon Collection offered for sale by the American Museum of Natural History. Of the paintings that he purchased, he donated 351 to the National Gallery of Art, located just a few blocks from the Smithsonian.

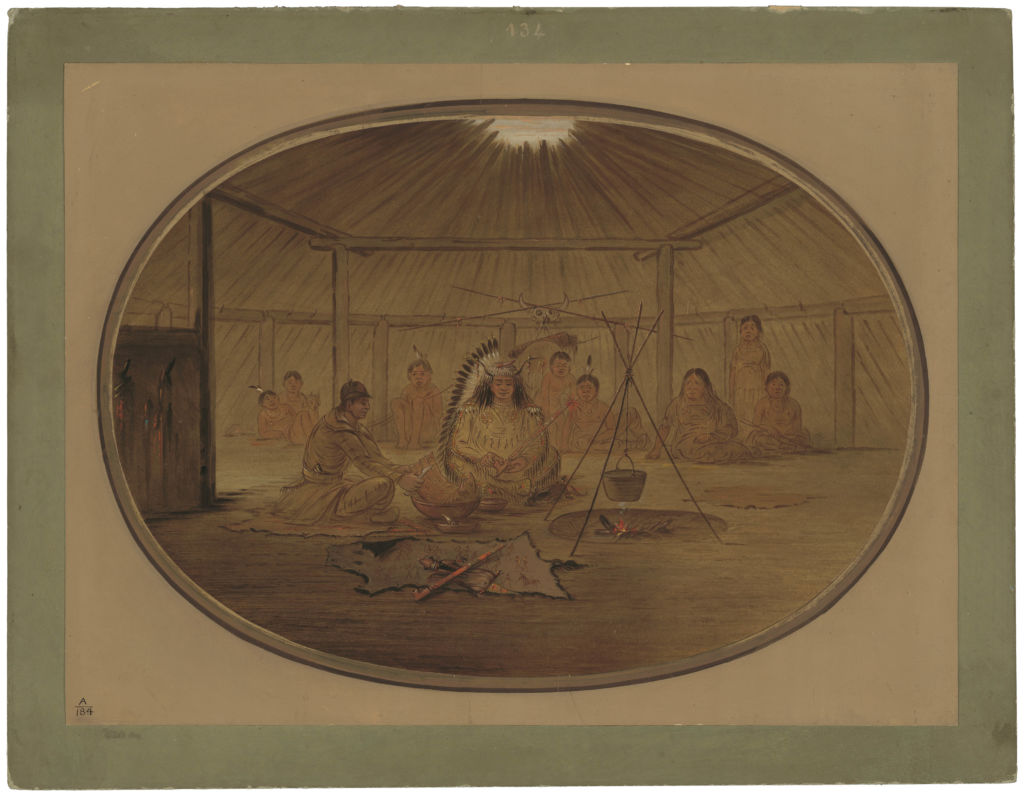

“Catlin Feasted by the Mandan Chief,” George Catlin (1796-1872), (Cartoon No. 133: The author feasted in the wigwam of Mah-to-toh-pa, the war chief of the Mandans, dining on a roast rib of buffalo and pemican.) Oil on card mounted on paperboard, 18 ¼ x 24 9/16 in., National Gallery of Art, Washington, Paul Mellon Collection

Leave A Comment