Today marks William Gilbert Gaul’s birthday (1855-1919).

Like another artist represented in the museum’s collection – Peter Moran – Gaul served as a special agent in 1890 for the eleventh census, focusing on American Indians in the United States. In particular, the artist observed the Standing Rock and Cheyenne River Reservations in North Dakota.

The census of 1890 was the first to use automated processing methods, which reduced the amount of time involved in charting the results, from eight years for the 1880 census, down to one year for the 1890 census. Out of a population of over sixty million residents, the census revealed that about 250,000 American Indians were living in the United States, a number that was quickly diminishing. The decline of this native population garnered national attention, with the designation of special agents assigned to the Indian portion of the eleventh census. As one of those special agents, Gilbert Gaul, along with other artists, documented the tribes and the people he encountered, capturing his observations in both photographs and paintings.

William Gilbert Gaul, Sioux and Wife, Semi-civilized, 1890. Report on the Indians Taxed and Not Taxed in the United States (except Alaska) at the Eleventh Census, 1890. Department of the Interior, Census Office. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1894.

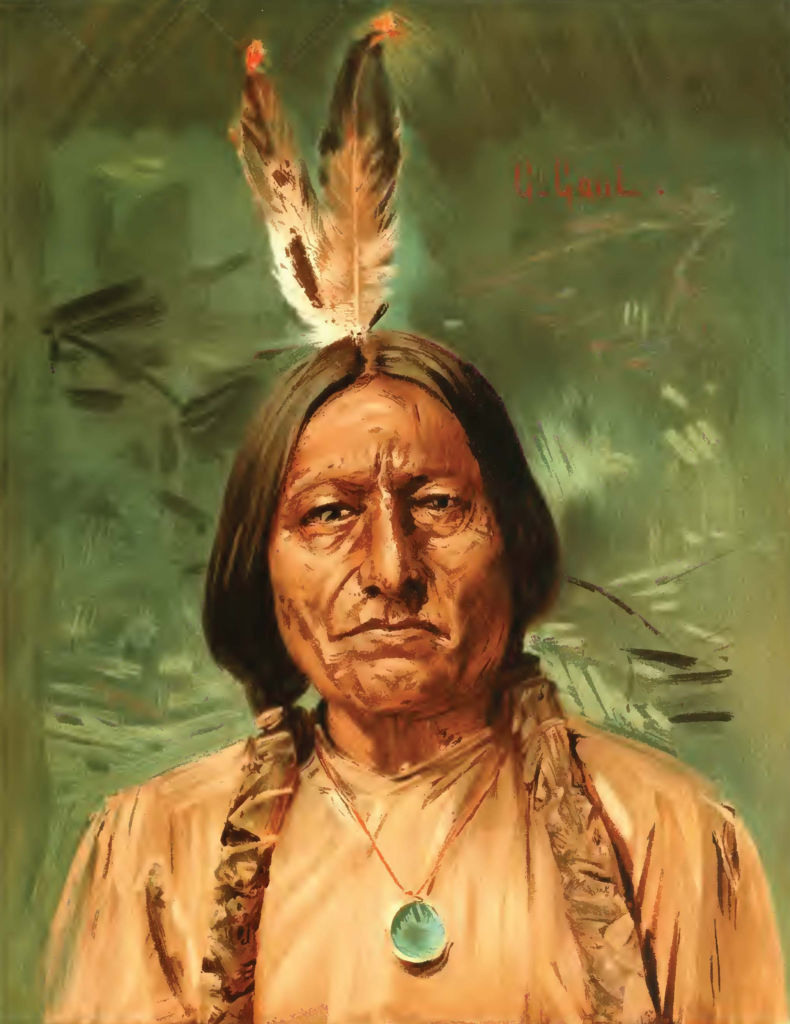

William Gilbert Gaul, Sitting Bull, 1890. Report on the Indians Taxed and Not Taxed in the United States (except Alaska) at the Eleventh Census, 1890. Department of the Interior, Census Office. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1894.

During his visit, Gaul painted from life a portrait of Sitting Bull, completed just months before the chieftain’s death.

William Gilbert Gaul, Sioux Camp, 1890. Report on the Indians Taxed and Not Taxed in the United States (except Alaska) at the Eleventh Census, 1890. Department of the Interior, Census Office. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1894.

What the artist witnessed was a changing culture. Gaul notes in his report that:

The day of buffalo robes and buckskins is passing away. With the Sioux breechcloths are no more. The Indian is no longer a gaily bedecked individual. Most of his furs and feathers have disappeared simultaneously with the deerskin. When he lost his picturesque buckskins he had to make his leggings of army blankets, red and blue.

Recording exactly what he saw, as demonstrated in the artist’s painting, The Pow-Wow, Gaul portrays the transition these tribes were undergoing. Rather than perpetuate a romanticized myth, the artist conveys the realities of reservation life, as these buffalo-hunting warriors of yesteryear have become dependent on government rations. Tipis, once made of hide, were now constructed with canvas or muslin. The painting shows the growing infiltration of Western society – the wagon, coffee pot, and kettle – as Native American traditions were gradually becoming relics of the past.

William Gilbert Gaul, The Pow-Wow, c.1890, oil on canvas, 18 1/8 x 24 1/8 inches

I’m trying to find a black & white done by Gilbert Gaul. It has a soldier standing on a bridge hold a smoking gun standing above a dead dog. I think the name of the picture is “Dead Dog”, or so I’ve been told. Any information that you can give me, would be a great help. Thank you for your time. Sincerely, Ken Triplett

Ken,

Thank you for contacting us. Unfortunately, no one on staff is familiar with the Gaul image about which you speak. I’m sorry we could not be of further assistance.

-Leslie Thompson

Adult Audiences Manager

Did Gilbert Gaul visit the Caribbean or tropics in his older years and did he do any paintings in black and white?

Sara –

Those are good questions. I believe Gilbert Gaul did visit the Caribbean, as well as Latin America and South America. He did work for some of the popular magazines of the day, so it’s possible he painted in B&W, but I can’t say for sure as I’m not familiar with his oeuvre. You might look for a copy of Reeves, John F., Gilbert Gaul. Exhibition catalogue, Cheekwood and Huntsville Museum of Art, 1975.