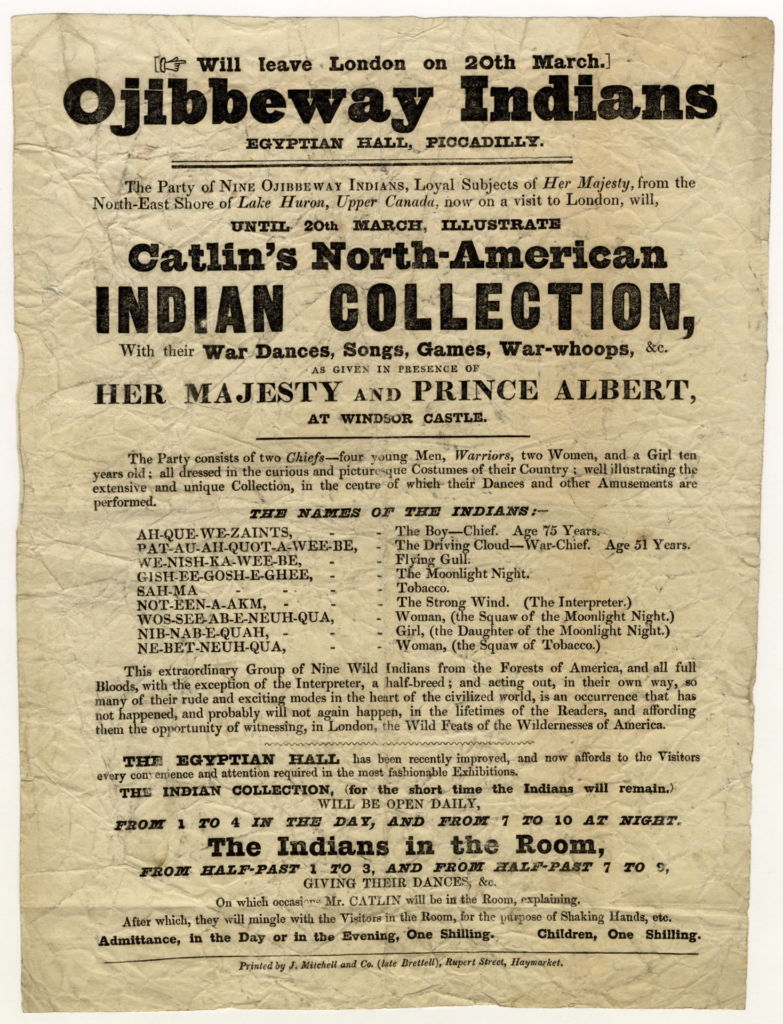

As mentioned previously, George Catlin went on several summer excursions West in the early 1830s to record the customs and characters of American Indian tribes he encountered. After 1837, Catlin the artist turned into Catlin the showman, touring the East Coast and Europe with his collection of paintings, costumes, weapons, and household artifacts. He called it his “Indian Gallery” or “Gallery Unique.” In doing so, Catlin inaugurated the elements of what was to become known as Wild West Shows.

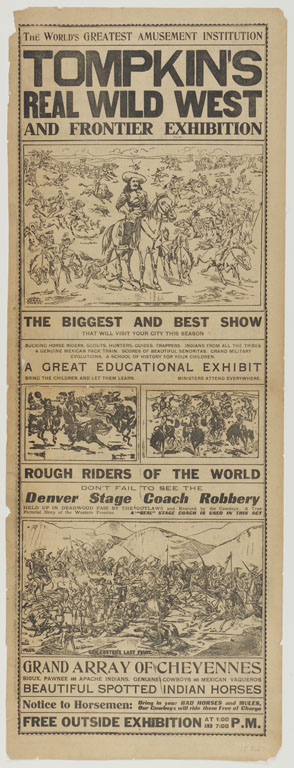

Unknown artist, The World’s Greatest Amusement Institution Tompkin’s Real Wild West Frontier Exhibition and European Circus, ca. 1911, Lithograph, Courtesy of Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

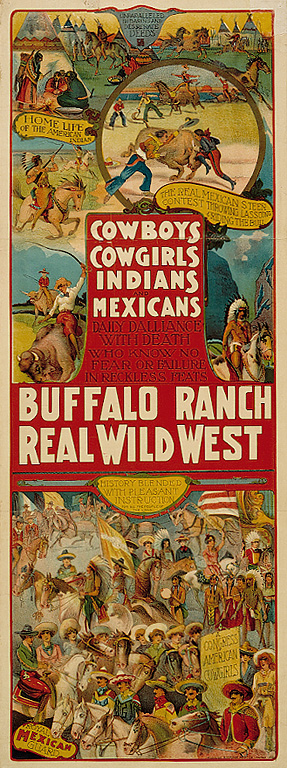

Unknown artist, Buffalo Ranch Real Wild West: Cowboys, Cowgirls, Indians, and Mexicans, ca. 1890-1910, Chromolithograph, Courtesy of Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

The Wild West Show as a form of entertainment did not become a major cultural phenomenon until the late 19th century, when Americans and Europeans became intrigued with the rapidly disappearing Plains frontier. All Wild West Showmen shared a goal – to create popular entertainments that provide spectators an opportunity to witness and appreciate replications of life on the Great Plains. Audiences of these shows typically experienced the portrayal of a simple, romantic world in which heroic people on horseback enjoyed untrammeled freedom, quickly eliminated evil, and ensured the success of the “American” way.

Erwin E. Smith, Part of the Wild West Show of Gordon W. Lillie “Pawnee Bill,” famous showman who was touring the Eastern states at the time Erwin E. Smith, the photographer, was attending the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Photographed against a painted backdrop. Boston, Massachusetts., 1908, Nitrate negative, Courtesy of Erwin E. Smith Collection of the Library of Congress on Deposit at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, © Erwin E. Smith Foundation

Erwin E. Smith, Performers with stage coach in Pawnee Bill’s Wild West Show., 1908, Gelatin dry plate negative, Courtesy of Erwin E. Smith Collection of the Library of Congress on Deposit at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, © Erwin E. Smith Foundation

Catlin pioneered much of the Wild West Show tradition, including conveying the look and feel of the prairies, its people, animals that roamed there, the joy of the hunt and chase, and colorful aspects of the frontier. The artist had witnessed the end of the Plains Indian culture – one built around family, ceremonial life, horsemanship, buffalo hunting, warfare and other pursuits free from outside influences. He believed that others would only know of the “vanishing” American Indian cultures through the visual record he had preserved, compelling him to reproduce and interpret the Plains Indian culture for the public and make a living in the process. Catlin conveyed his ideas through the reigning media of the day – paintings, museum-like collections, books, and lectures – and traveled his collection around the world.

Broadside for Catlin exhibit in Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly, England, ca.1844, Courtesy Toronto Public Library, Gift of the Metcalf Family in Honour of Robert F. Reid

George Catlin | Nine Ojibbeway Indians in London | 1861 – 1869 | Oil on card mounted on paperboard

George Catlin’s Indian Gallery, The Grand Salon, Renwick Gallery, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Photo by Il Primo Uomo on Flickr

Producing his enterprise was no simple – or inexpensive – task. Catlin had to hire many helpers. His collection of art and artifacts required proper packing and shipping. In addition to the hundreds of paintings, there were several thousand artifacts: tobacco pipes and domestic objects; weapons of war, the tomahawks, scalping knives, and clubs; and two live grizzly bears, which proved too troublesome for the European portion of his traveling exhibit. With a limited supply of affordable and fashionable exhibition space, Catlin often settled on salons at law buildings, old chapels, old theaters, and public buildings. His paintings and artifacts crowded the walls, displayed in what is referred to as “salon style,” in which images are stacked on top of each other from floor to ceiling. The exhibition’s festivities began promptly at 7:30pm. Electricity not yet available, lighting in the evening hours was provided by candles or whale oil lamps. Can you imagine?!

**Information for this post was collected by SRM research volunteer Shelle McMillen. Thank you, Shelle!**

Leave A Comment