During his residence in Montana, Charles Russell encountered Indigenous people, both on the northern plains of the state and from neighboring tribes in Alberta, Canada. He lived in the area where Plains Indian Sign Language (PISL), also known as Hand Talk among the Native community, was an important communication system among the Plains tribal members. Due to his relationships with many members of nearby Indigenous tribes, Russell learned signs of PISL and incorporated them into some of his paintings.

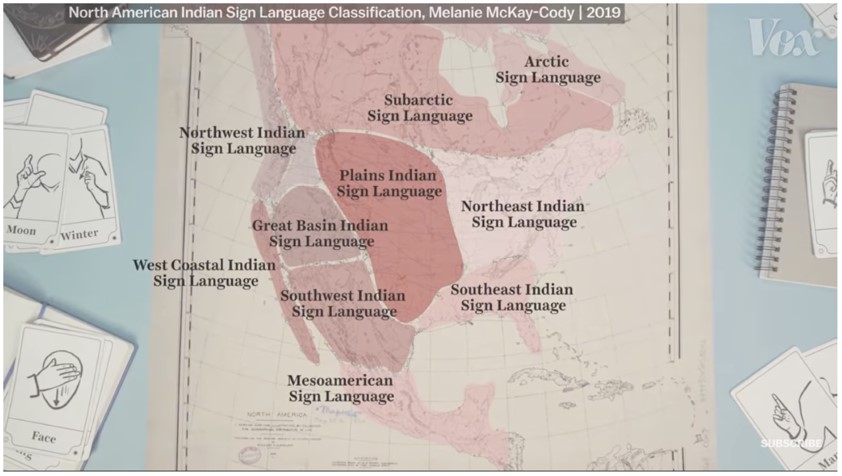

Mapping of North American Indian Sign Language

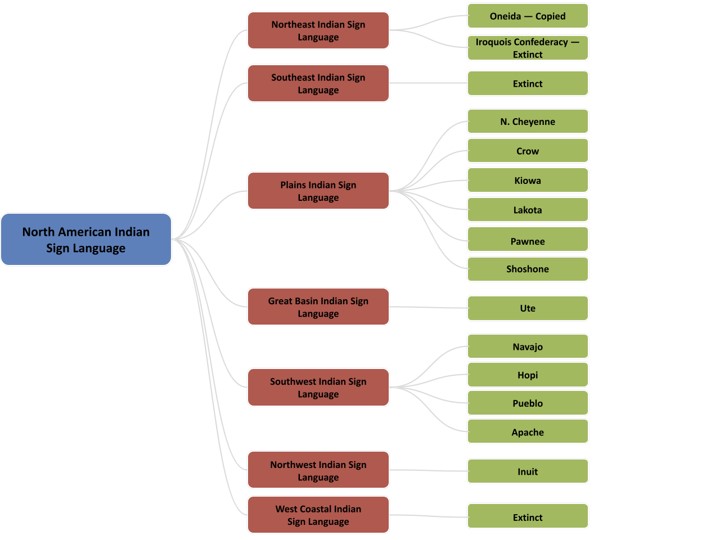

Outline of corresponding tribes with various regional variations of North American Indian Sign Language

North American Indian Sign Language is the umbrella term under which there are different regional variations of Hand Talk, like Plains Indian Sign Language. PISL is one of the oldest languages in North America once used widely by both deaf and hearing folk among Indigenous peoples, for purposes of economics, special ceremonies, ritual, storytelling, and more. North American Indian Sign Language influenced the formation of American Sign Language (ASL), but Hand Talk has largely been forgotten over the years.

Dr. Melanie McKay-Cody, a Deaf Cherokee scholar, is a linguist and socio-cultural anthropologist who has been studying critically-endangered Indigenous Sign Languages in North America since 1994 and helps different tribes preserve their tribal signs.

Unlike most of the non-Native and non-deaf artists of this time period, Charles Russell was a unique artist who portrayed the Plains Natives using authentic tribal signs. After examining Russell’s paintings, Dr. McKay-Cody identified several instances of the artist’s incorporation of PISL into his compositions.

Sign language is a three-dimensional language. Unfortunately, in the case of Russell’s artwork, because the signs are within a two-dimensional medium frozen in time – paintings – it can be difficult to firmly identify the exact meaning of the sign represented. But scholars like Dr. McKay-Cody can confer with someone who actively practices PISL to ensure correct interpretation and determine that the meaning matches the setting or the environment that’s painted.

Charles M. Russell | Captain William Clark of the Lewis and Clark Expedition Meeting with the Indians of the Northwest | 1897 | Oil on canvas | 29.5 x 41.5 inches

Throughout Russell’s work, Dr. McKay-Cody found many different incorporations of a V-handshape. This handshape equates to many different meanings, depending on the movement that would accompany the sign. It could be “look,” as in the directional command to look forwards, backwards, right or left. It could also mean “dog.”

Take a look at Russell’s 1897 painting Captain William Clark of the Lewis and Clark Expedition Meeting with the Indians of the Northwest. There are 2 signs in this artwork. See the gentleman standing in the middle between the two figures shaking hands? He’s holding a V-handshape on his chest. Historians have identified this man as Toussaint Charbonneau, husband of Sacajawea and an interpreter for the Lewis and Clark expedition.

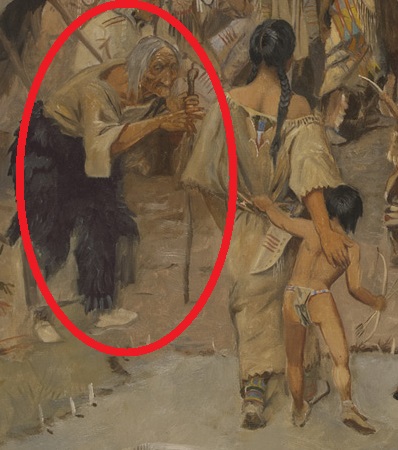

There’s another figure in the painting making a sign. See the old woman in the front left side of the painting? She’s also holding a V-handshape across her chest. It could be that the woman is saying to the younger figure, “Look! There’s an important conversation going on over there. We need to be paying attention to what they’re talking about.” That’s just one possible interpretation.

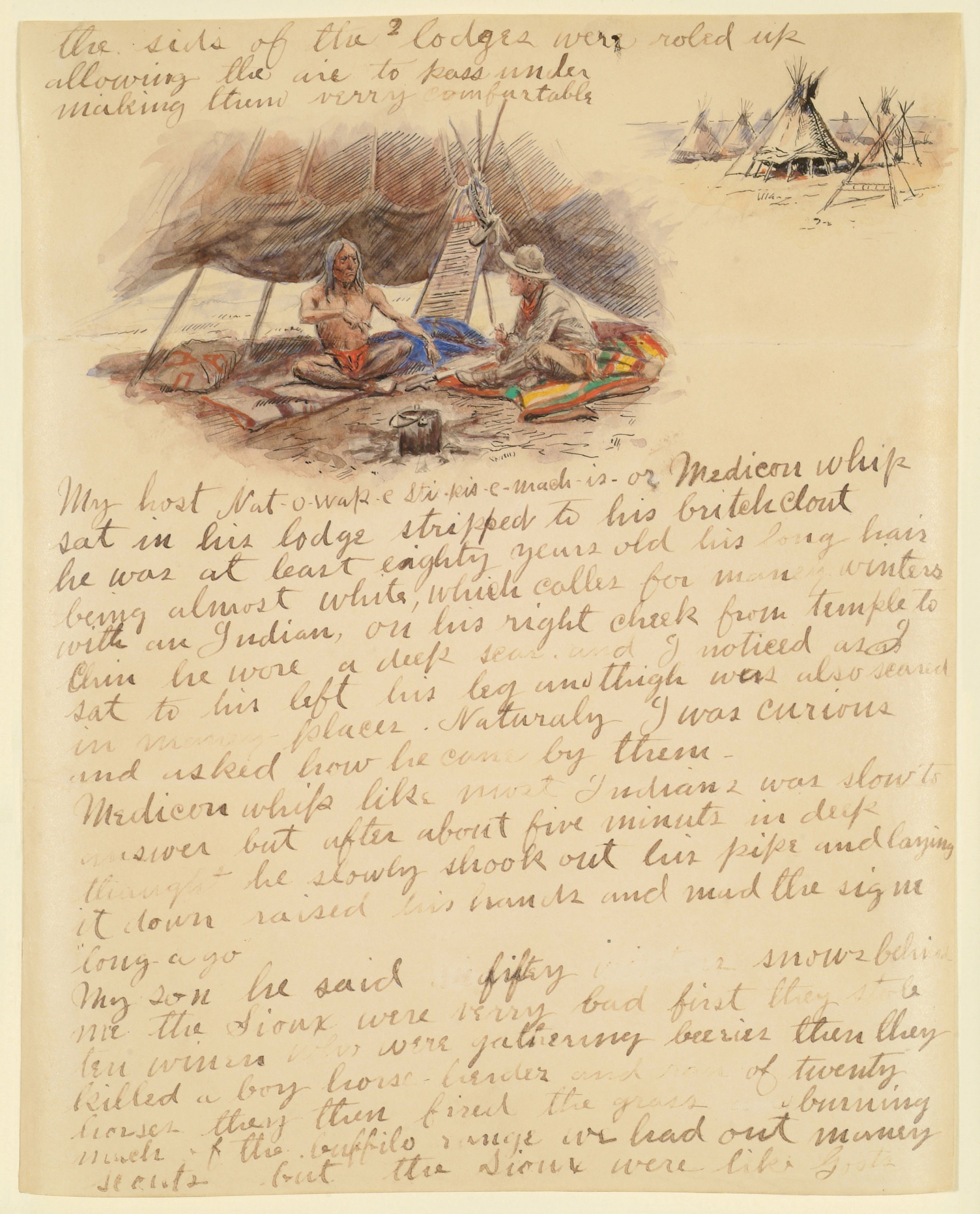

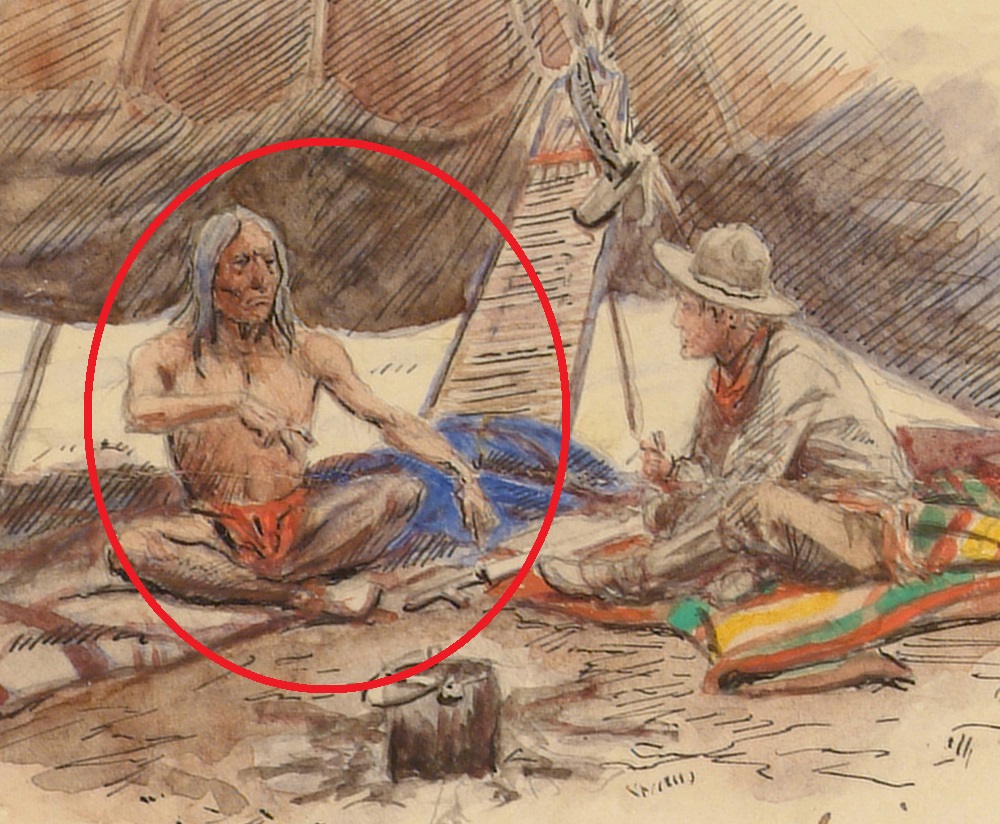

Charles M. Russell, Letter from Charles M. Russell to George W. Kerr, September 29, 1902, pen & ink, pencil, watercolor, and gouache on paper, Private Collection

Here’s another instance of the V-handshape in an illustrated by Charles Russell. We see the figures in conversation. The Indigenous figure on the left is telling a story. The content of the letter itself is about a story that was told to Russell that the artist later rendered in a couple of subsequent paintings. With the sign indicated, it’s possible that the Indigenous man is talking about a horse walking, or it could be a dog.

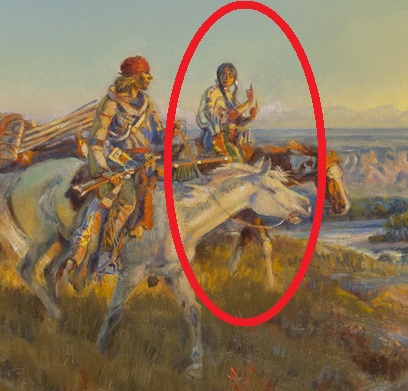

Charles M. Russell | When White Men Turn Red | 1922 | Oil on canvas | 24 x 36.25 inches

As Dr. McKay-Cody looked further into the Sid Richardson Museum’s collection, she found instances of other handshape-based signs. Look at the female figure in Russell’s 1922 When White Men Turn Red. She is in the middle of making a sign which represents people. Notice all of the people down below in the village. She could be saying “We’re going to see my people.”

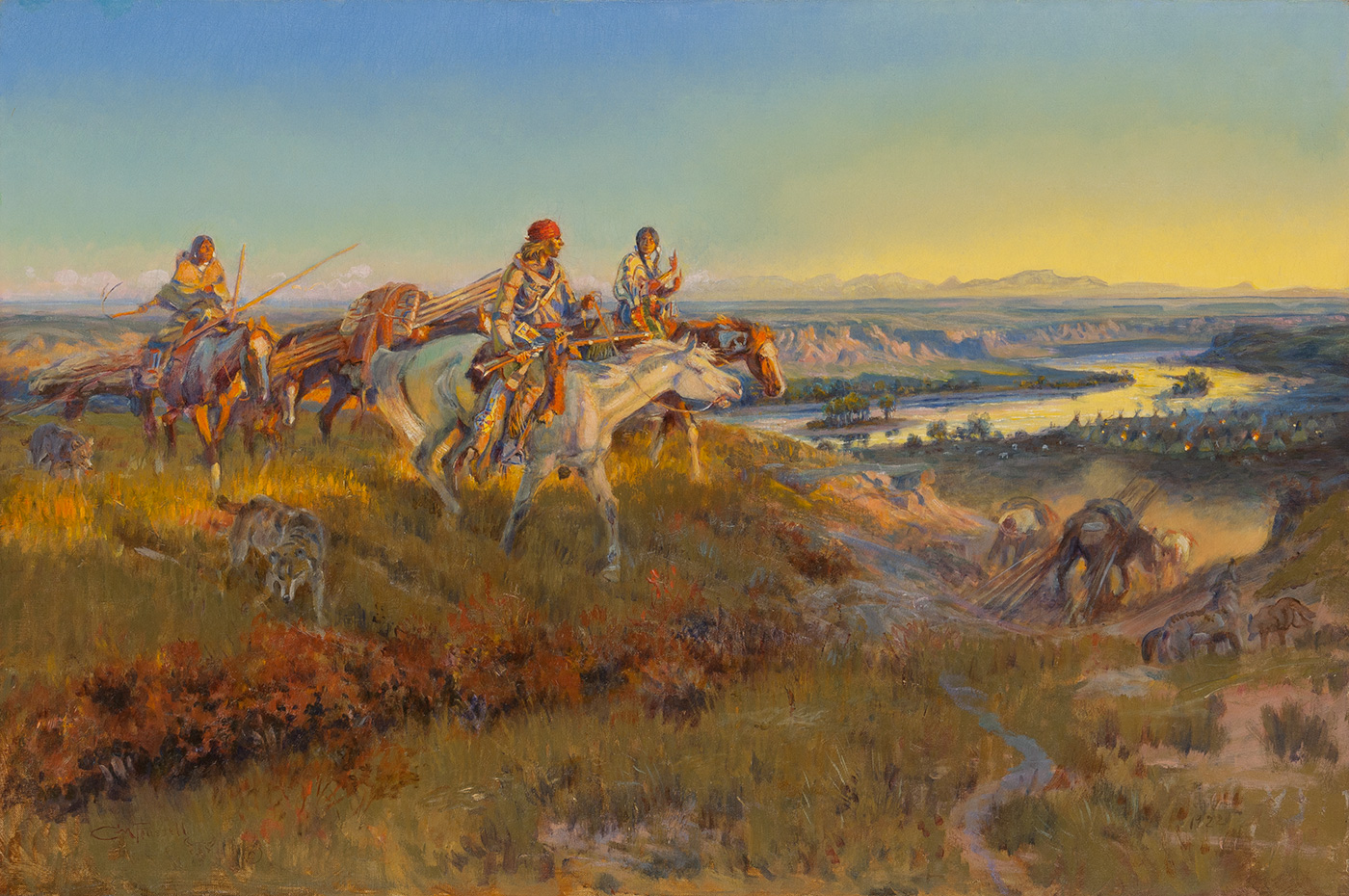

Charles M. Russell | In the Wake of the Buffalo Runners | 1911 | Oil on canvas | Private Collection

Another instance of Hand Talk is evident in a painting featured in our current exhibition, Charles M. Russell: Storyteller Across Media. Look at the older female figure in the back of Russell’s 1911 painting In the Wake of the Buffalo Runners. She is making the open 5 handshape. This is the sign for “go,” or “let’s go this way.” It could be made with a questioning expression as in, “should we go this way?” or “are we going this way?”

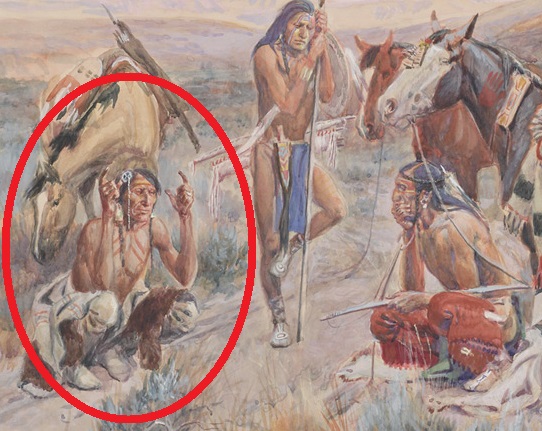

Charles M. Russell | First Wagon Trail (First Wagon Tracks) | 1908 | Pencil, watercolor and gouache on paper | 18.25 x 27 inches

In Russell’s 1908 watercolor First Wagon Trail, notice the figure on the far left. He is making the curved L-handshape. This sign refers to bison. In the painting, it’s clear that the group of Indigenous men are puzzling over what manner of beast has left the tracks in the dust. Not having yet had contact with the wagon trains of colonial settlers, one figure makes the guess of buffalo.

Charles M. Russell | Bringing Up the Trail | 1895 | Oil on canvas | 22.875 x 35 inches

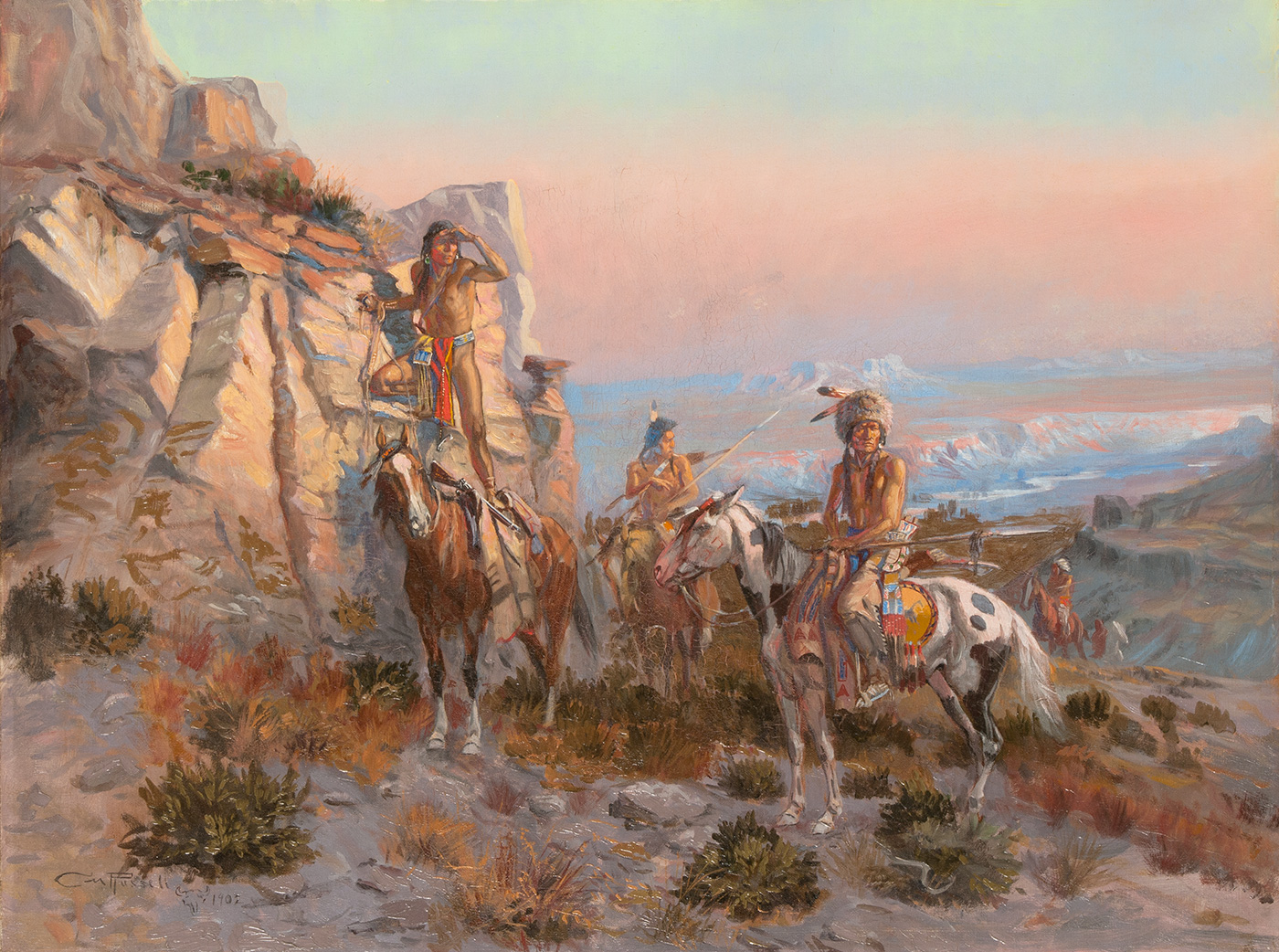

Charles M. Russell | Trouble Hunters | 1902 | Oil on canvas | 22 x 29.125 inches

In two of the Russell paintings in the museum’s collection, Dr. McKay-Cody found examples of the same sign. Notice how the central figure in both paintings above have a hand over the top of the eyes. They’re blocking the sun with their hands and, looking at their expressions, they’re trying to look far away. Both historically and today in the Deaf Native community, this is the sign used for scout.

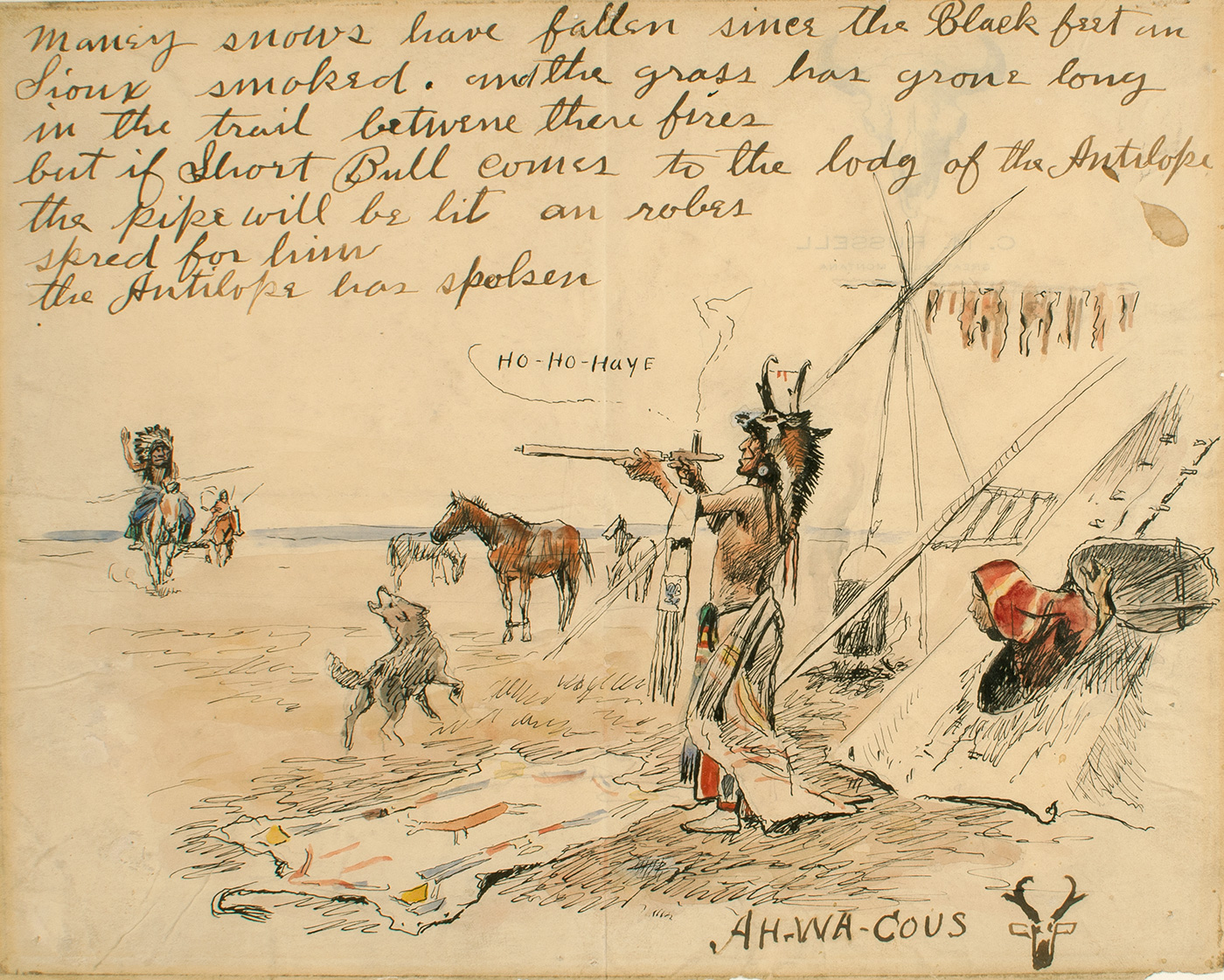

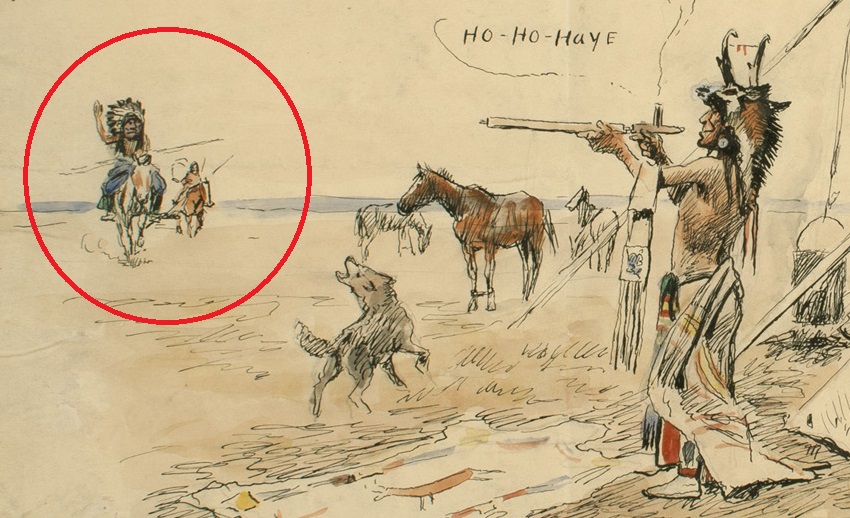

Charles M. Russell | Maney Snows Have Fallen…(Letter from Ah-Wa-Cous (Charles Russell) to Short Bull) | c. 1909-10 | Watercolor, pen & ink on paper | 8 x 10 inches

Probably one of the best known Hand Talk signs is the image of a person with a raised hand, as seen in Russell’s c. 1909-10 illustrated letter Maney Snows Have Fallen…(Letter from Ah-Wa-Cous (Charles Russell) to Short Bull). Some may incorrectly read this as the stereotypical English translation, “how.” But this sign has a purpose, a function. It means “I am here, I am present. I come in peace. I intend this meeting to be peaceful.” It can also mean “stop,” so that everyone in the party stops. There are different translations depending on the context.

I had not thought about the three dimensional aspect of signing among indians. This realization makes it almost impossible to say with complete confidence the exact meaning of a sign. Obviously context [facial expression, body language and what occurred before the sign was made, etc] makes a big difference in what the sign might mean. Especaily it’s emotional content.

[…] language depicted in the famous artwork of explorer and painter Charles Russell. Visit here to see examples in these […]

[…] https://sidrichardsonmuseum.org/plains-indian-sign-language-and-charles-russell/ […]