Our current exhibit looks at different aspects of the American West, one theme of which explores Western Archetypes. As evidenced in his paintings and bronzes, artists like Frederic Remington created a cast of archetypal western heroes that he returned to again and again from the cowboy, to the brave solider, and the mountain men. One well-known western archetype is that of explorer, figures who carved out the trails west, with the most famous explorers of the American frontier being Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. These western heroes are represented in the exhibit with Charles Russell’s 1897 painting Captain William Clark of the Lewis and Clark Expedition Meeting with the Indians of the Northwest.

Captain William Clark of the Lewis and Clark Expedition Meeting with the Indians of the Northwest | Charles M. Russell | 1897 | Oil on canvas | 29.5 x 41.5 inches

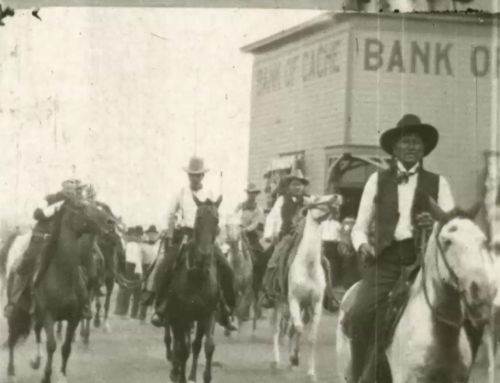

This painting depicts a specific event in which members of the expedition have stopped to meet with a band of American Indians – likely the Mandan Indians. Here, Clark steps forward to shake hands with the leader while Charbonneau, husband of Sacajawea, interprets and Clark’s African-American slave, York, looks on.

The sole Black member of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, York was the first documented Black American enslaved person to travel across the continent.[1] Nearly every student in the U.S. learns the basic story of the Lewis & Clark expedition at some point in school. But how much do you know about York, a key member of the Corps of Discovery?

York’s Life Prior

Few details are known about York’s life prior to the expedition. His father, Old York, and his mother, Rose, were both enslaved people of William Clark’s father in Virginia. The Clark family moved from Virginia to Kentucky in 1784, and York was among the 12 enslaved people who traveled with them. York had grown up with young William, working as his “companion” and later, following custom in the South, as “manservant.” William Clark had about 18 enslaved people, but York was closest to him.[2]

Stereotypes of York

York played a significant role in one of the most notable explorations in history and has been the source of many myth-making stories. Since the expedition, each story of York has been presented by different generations of historians that reflects the interracial behaviors, politics, and dynamics of that generation. Some stories say that York was a man of great physique and stamina; others say that he clowned and womanized his way through the journey; or that he made no significant contributions to the outcome of the expedition.

York played a significant role in one of the most notable explorations in history and has been the source of many myth-making stories. Since the expedition, each story of York has been presented by different generations of historians that reflects the interracial behaviors, politics, and dynamics of that generation. Some stories say that York was a man of great physique and stamina; others say that he clowned and womanized his way through the journey; or that he made no significant contributions to the outcome of the expedition.

Scholar Darrell Millner divides the scholarly treatment of York into two categories of stereotypes: the “Sambo” and the “superhero.” Of the two, the Sambo treatment dominated stories of York for the first 200 years since the expedition. In the Sambo tradition, York is characterized as a buffoon, someone who’s only purpose was to make his companions laugh, as if a performer of a minstrel show.[3] On the other hand, the superhero interpretation elevates York to near superhuman status. In this tradition, York is portrayed as a self-sacrificing Black hero who has overcome all of the obstacles he endures whether from his slave master Clark or from the hostilities of the frontier. Both traditions, Sambo and superhero, tend to overlook or sacrifice accuracy and integral details in their portrayals.[4]

During the Journey

In reality, accounts show that York was expected to work in the same fashion as and along with the other men of the expedition. Clark chose to include York in this exclusive Corps, which required all members to pull their own weight. In fact, York was fully armed, able to move about freely, and was often respected and admired by those the expedition met along the journey.[5] In November of 1805, after the Corps reached the Pacific Ocean, in deciding where to camp and wait out winter, Lewis & Clark asked each member of the expedition, including Sacagawea and York, to cast their vote.[6] Additionally, on the return trip in 1806, the crew relied on York to serve as a trader with the American Indians they encountered. Lewis wrote:

“McNeal and York were sent on a trading voyage over the river this morning, having exhausted all our merchandize we are obliged to have recourse in every subterfuge in order to prepare in the most ample manner in our power to meet that wretched portion of our journey, the Rocky Mountain…Our traders McNeal and York were furnished with the buttons which Capt. C. and myself cut off our coats, some eye water and Basilicon which we made for that purpose and some Phials and small tin boxes which I had brought out with Phosphorus. In the evening they returned with about 3 bushels of roots and some read having made a successful voyage, not much less pleasing to us than the return of a good cargo to an East India Merchant”[7]

Undoubtedly, York had attained a position of trust and acceptance within the Corps during the expedition.

Charles M. Russell (1864-1926), Lewis and Clark on the Lower Columbia, 1905, Opaque and transparent watercolor over graphite underdrawing on paper, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas; 1961.195

After the Journey

Upon return, what was life like for an enslaved person whose contributions were acknowledged in the creek and islands that Clark named for him along the journey?[8] For years, historians told the story that Clark granted York his freedom in compensation for his services on the expedition. However, with the 1988 discovery of Clark family papers, contemporary scholarship shows that Clark did not free York upon return to St. Louis. Rather, Clark kept York an enslaved person until about 1816. The relationship between the two men disintegrated quickly. For example, on November 9, 1808, Clark wrote his brother Jonathan Clark that he would:

“send York…and promit him to stay a fiew weeks with his wife. He wishes to stay there altogether and hire himself which I have refused. He prefers being sold to return[ing] here. He is serviceable to me at this place, and I am determined not to sell him, to gratify him, ..if any attempt is made by York to run off, or refuse to provorm his duty as a slave, I wish him sent to New Orleans and sold, or hired out to some severe master until he thinks better of such conduct.”[9]

The story of the Lewis & Clark Expedition is a long and complex one. Unfortunately, the expedition journals provide few entries about York’s physical appearance. No painting was ever made of York, so despite later representations of him in paintings like Russell’s, we actually don’t know what York really looked like.[10] However, the availability of long-lost information like the discovery of the Clark Family Papers allows historians to reassess the myths and folklore surrounding figures like York and portray the realities of this epic saga of our nation’s history.

[1] Darrell M. Milner, “York of the Corps of Discovery: Interpretations of York’s Character and His Role in the Lewis and Clark Expedition.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 104, no. 3 (2003): 304.

[2] Robert Betts, In Search of York: The Slave Who Went to the Pacific with Lewis & Clark (Boulder, CO: Colorado Associated University Press, 1985): 83-94.

[3] Milner, 306.

[4] Ibid, 307.

[5] Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 13 vols (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986-87), 2:279.

[6] Ibid, 6:84.

[7] Ibid, 7:324.

[8] Ibid, 8:253, 6:450, 6:464.

[9] James J. Holmberg, “I Wish You to See and Know All: The Recently Discovered Letters of William Clark to Jonathan Clark,” We Proceeded On 18:4 (November 1992): 7-8.

[10] Milner, 325.

[…] Continuing exploration of our current exhibit, another studied theme centers around the Bison and the Plains Indian. One gallery wall of artworks features the chaos and movement during the actual hunt. Opposite that wall is a progression of paintings highlighting Plains Indian women and their role in relation to moving camp during hunting season created by Charles Russell from early in his career into the 1910s, representing a 20-year span of the artists treatment of this theme. […]

[…] and Clark Expedition (1804-1806), is portrayed in this painting with a commanding presence (see York: Of Myth and Fact). This was one of eight Charlie Russell paintings owned by Robert Vaughn, an older neighbor and […]