From time to time, I like to break away from my office to walk through our museum galleries and enjoy the artwork that I often write about on this blog. During one of those leisurely strolls I caught a glimpse of something that was unfamiliar. In one of the paintings from our current exhibition, Take Two, I noticed a strange creature hanging from the belt of one of the figures. When I looked closely, I noticed another figure sporting a similar accessory. I then began to carefully examine the rest of the Catlin images and spotted this particular object in two more paintings. What is that?!

George Catlin | Nine Ojibbeway Indians in London | 1861 – 1869 | Oil on card mounted on paperboard

Detail

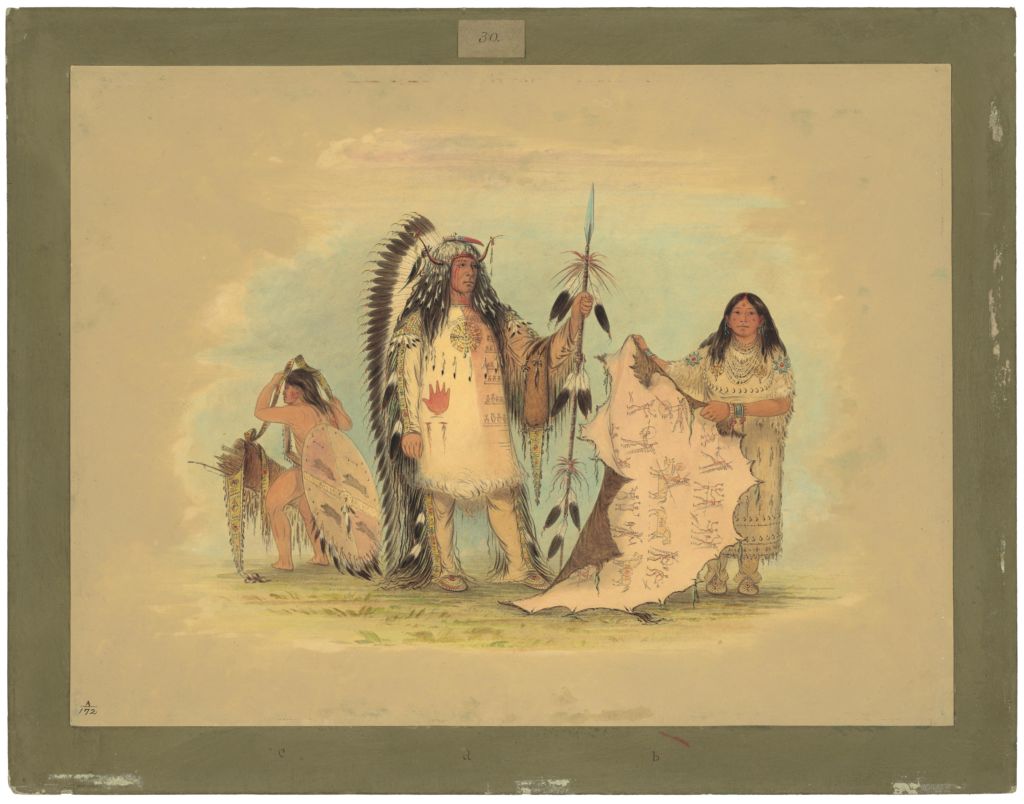

“Mandan War Chief with His Favorite Wife,” George Catlin (1796-1872), (Cartoon No. 30) Oil on card mounted on paperboard, 18 ¼ x 24 5/16 in., National Gallery of Art, Washington, Paul Mellon Collection

Detail

It’s an otter! But why are they hanging off men’s belts or sitting around like handbags? Thus the search began to uncover this mystery. After reading through Catlin’s writings, I found my answer. In his famous Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Conditions of North American Indians, of which we have a rare copy currently on display, Catlin mentions his encounters with these ornamented otters. In some instances, such as his experience with a Blackfoot brave, Pe-toh-pee-kiss (The Eagle Ribs), the otter skins were made for medicine bags. These medicine bags had great meaning and importance, so much so, that when its owner dies, it is placed in his grave and decays with his body.

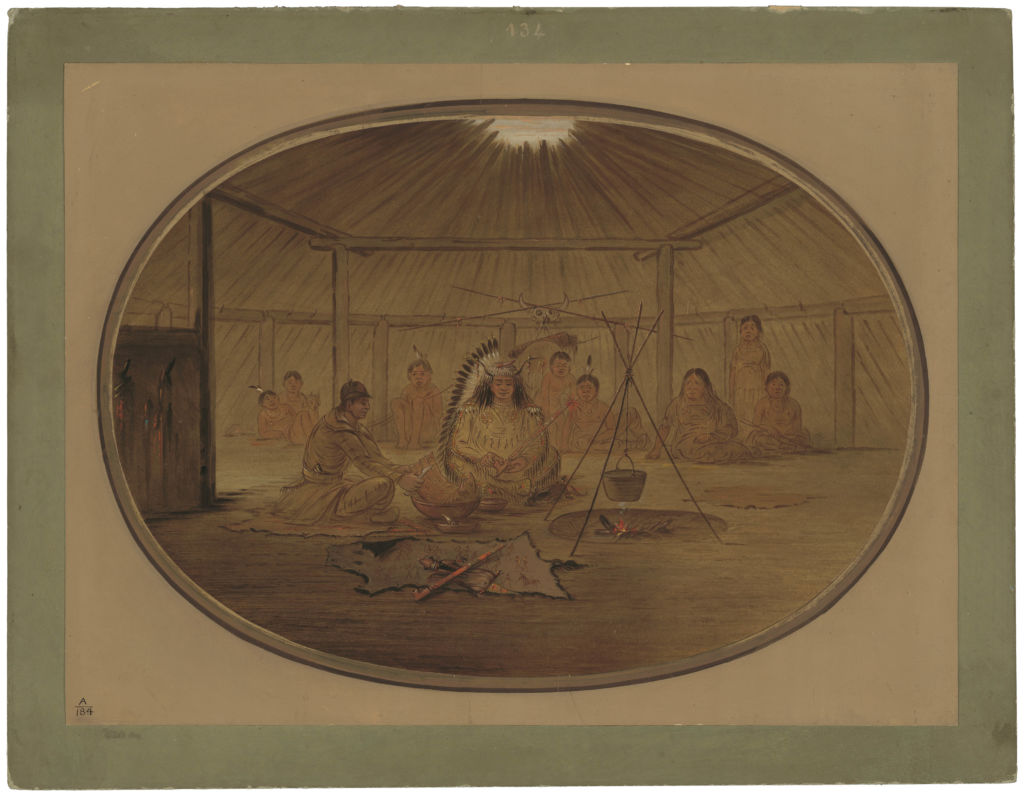

“Catlin Feasted by the Mandan Chief,” George Catlin (1796-1872), (Cartoon No. 133: The author feasted in the wigwam of Mah-to-toh-pa, the war chief of the Mandans, dining on a roast rib of buffalo and pemican.) Oil on card mounted on paperboard, 18 ¼ x 24 9/16 in., National Gallery of Art, Washington, Paul Mellon Collection

Detail

Detail

A more common use for otter skins among the tribes Catlin encountered was as a pouch for k’nick-k’neck, or tobacco. The artist demonstrates this custom in his painting Catlin Feasted by the Mandan Chief. Catlin dines on roasted buffalo ribs while the Mandan Chief Four Bears prepares his pipe for an after-dinner smoke. Next to Four Bear’s foot lies his otter-skinned tobacco pouch. Another can be found on display in the foreground of the painting.

In Letter No. 16. from Catlin’s Letters and Notes, the artist describes this very scene:

I spoke in a former Letter of Mah-to-toh-pa (the four bears), the second chief of the nation, and the most popular man of the Mandans — a high-minded and gallant warrior, as well as a polite and polished gentleman. Since I painted his portrait, as I before described, I have received at his hands many marked and signal attentions; some of which I must name to you, as the very relation of them will put you in possession of many little forms and modes of Indian life, that otherwise might not have been noted.

About a week since, this noble fellow stepped into my painting-room about twelve o’clock in the day, in full and splendid dress, and passing his arm through mine, pointed the way, and led me in the most gentlemanly manner, through the village and into his own lodge, where a feast was prepared in a careful manner and waiting our arrival. The lodge in which he dwelt was a room of immense size, some forty or fifty feet in diameter, in a circular form, and about twenty feet high — with a sunken curb of stone in the center, of five or six feet in diameter and one foot deep, which contained the fire over which the pot was boiling. I was led near the edge of this curb, and seated on a very handsome robe, most ingeniously garnished and painted with hieroglyphics; and he seated himself gracefully on another one at a little distance from me; with the feast prepared in several dishes, resting on a beautiful rush mat, which was placed between us.

The simple feast which was spread before us consisted of three dishes only, two of which were served in wooden bowls, and the third in an earthen vessel of their own manufacture, somewhat in shape of a bread-tray in our own country. This last contained a quantity of pem-I-can and marrow fat; and one of the former held a fine brace of buffalo ribs, delightfully roasted; and the other was filled with a kind of paste or pudding, made of the flour of the “pomme blanche”, as the French call it, a delicious turnip of the prairie, finely flavored with the buffalo berries, which are collected in great quantities in this country, and used with divers dishes in cooking, as we in civilized countries use dried currants, which they very much resemble.

A handsome pipe and a tobacco-pouch made of the otter skin, filled with k’nick-k’neck (Indian tobacco), laid by the side of the feast; and when we were seated, my host took up his pipe, and deliberately filled it; and instead of lighting it by the fire, which he could easily have done, he drew from his pouch his flint and steel, and raised a spark with which he kindled it. He drew a few strong whiffs through it, and presented the stem of it to my mouth, through which I drew a whiff or two while he held the stem in his hands. This done, he laid down the pipe, and drawing his knife from his belt, cut off a very small piece of the meat from the ribs, and pronouncing the words “Ho-pe-ne-chee wa-pa-shee” (meaning a medicine sacrifice), threw it into the fire.

He then (by signals) requested me to eat, and I commenced, after drawing out from my belt my knife (which it is supposed that every man in this country carries about him, for at an Indian feast a knife is never offered to a guest). Reader, be not astonished that I sat and ate my dinner alone, for such is the custom of this strange land. In all tribes in these western regions it is an invariable rule that a chief never eats with his guests invited to a feast; but while they eat, he sits by, at their service, and ready to wait upon them; deliberately charging and lighting the pipe which is to be passed around after the Feast is over. Such was the case in the present instance, and while I was eating, Mah-to-toh-pa sat cross-legged before me, cleaning his pipe and preparing it for a cheerful smoke when I had finished my meal. For this ceremony I observed he was making unusual preparation, and I observed as I ate, that after he had taken enough of the k’nick-k’neck or bark of the red willow, from his pouch, he rolled out of it also a piece of the “castor,” which it is customary amongst these folks to carry in their tobacco-sack to give it a flavor; and, shaving off a small quantity of it, mixed it with the bark, with which he charged his pipe. This done, he drew also from his sack a small parcel containing a fine powder, which was made of dried buffalo dung, a little of which he spread over the top, (according also to custom,) which was like tinder, having no other effect than that of lighting the pipe with ease and satisfaction. My appetite satiated, I straightened up, and with a whiff the pipe was lit, and we enjoyed together for a quarter of an hour the most delightful exchange of good feelings, amid clouds of smoke and pantomimic signs and gesticulations.

[…] which members of the expedition have stopped to meet with a band of American Indians – likely the Mandan Indians. Here, Clark steps forward to shake hands with the leader while Charbonneau, husband of Sacajawea, […]