Recently, I was spending some time walking with a colleague around our current exhibition, Charles M. Russell: Storyteller Across Media. We were lingering in one corner of the gallery that highlights a collection of objects and artworks centered around the subject of “counting coup.”

What is counting coup? Counting coup was a system of graduated points wherein the first man to touch an enemy was awarded a first coup or “direct hit.” To count coup, one might use his hand, bow, lance, or perhaps rattles or whips.

Charles M. Russell | Counting Coup (Medicine Whip) | 1902 | Oil on canvas | 18.125 x 30.125 inches

Russell painted this deed in action in his 1902 painting Counting Coup. The artwork shows a battle between the Bloods [the Kainai] – a branch of the Blackfoot [the Niitsitapi] – and the Sioux [the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ]. This composition was based on the story recounted to Russell by an aged Blackfoot when the artist was visiting the Blood Indians [the Kainai] on their reservation near Calgary in 1888. In its day, the painting was hailed as Russell’s best work to date in “grouping, action and technic [sic].”

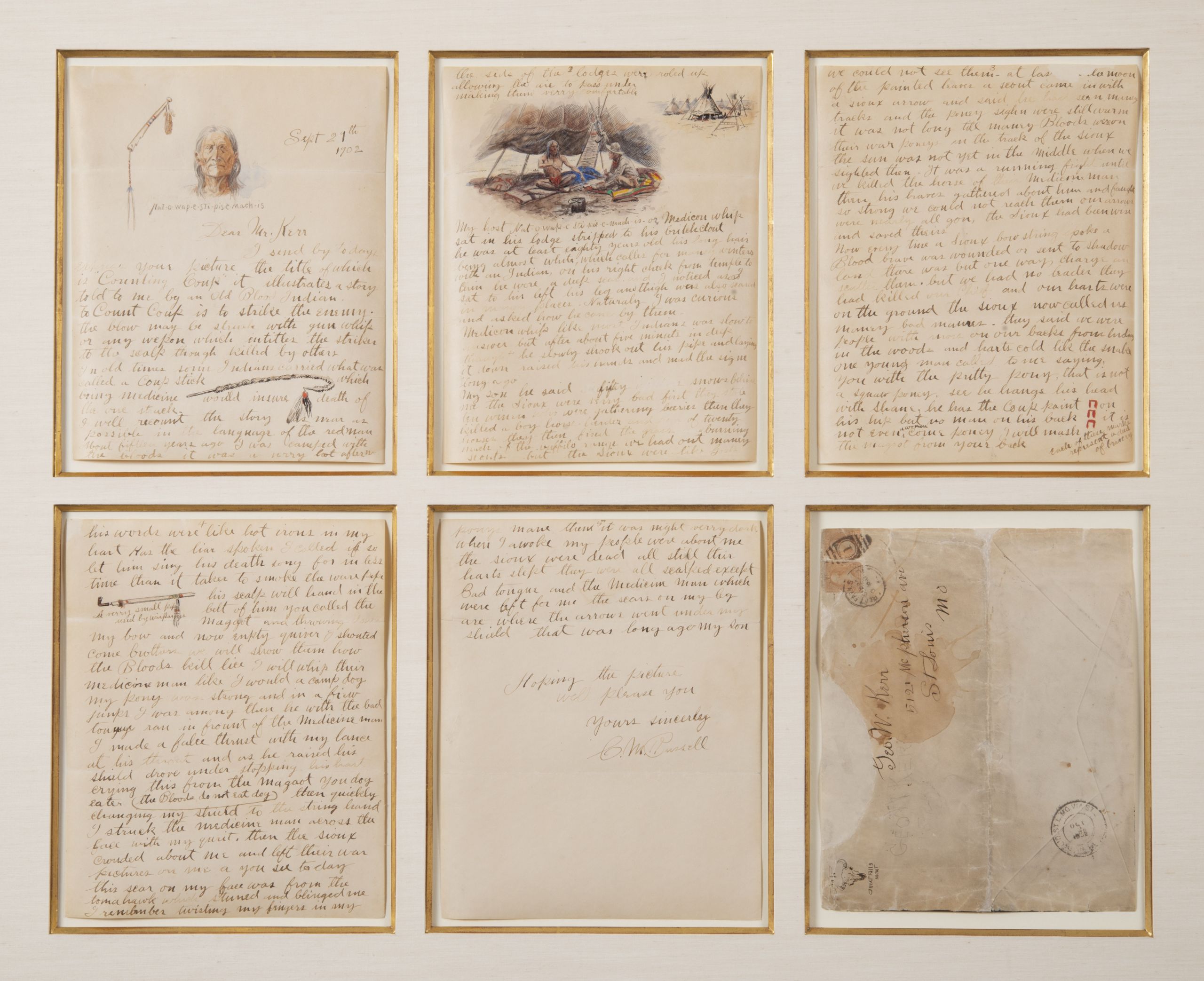

Russell provides a more detailed account of the story in a multi-paged illustrated letter he wrote to his patron George W. Kerr that better explains the genesis of the 1902 painted rendition of Counting Coup.

Charles M. Russell | Letter from Charles M. Russell to George W. Kerr | September 29, 1902 | Pen & ink, pencil, watercolor, and gouache on paper | Private Collection

Dear Mr. Kerr – I send by todays – express your picture the title of which – is “Counting Coup” it illustrates a story – told to me by an old Blood Indian. to Count Coup is to strike the enemy. the blow may be struck with gun whip – or any wepon which entitles the striker – to the scalp though killed by others – In old times some Indians carried what was – called a Coup stick which – bring medicine would insure death of the one struck. I will recount the story as near as – possible in the language of the redman – About fifteen years ago I was camped with – the Bloods it was a verry hot afternoon the sides of the lodges were roled up – allowing the aire to pass under – making them verry comfortable – My host Nat-o-wap-e-sti-pis-e-mach-is- or Medicine whip – sat in his lodge stripped to his britch clout – he was at least eighty years old…

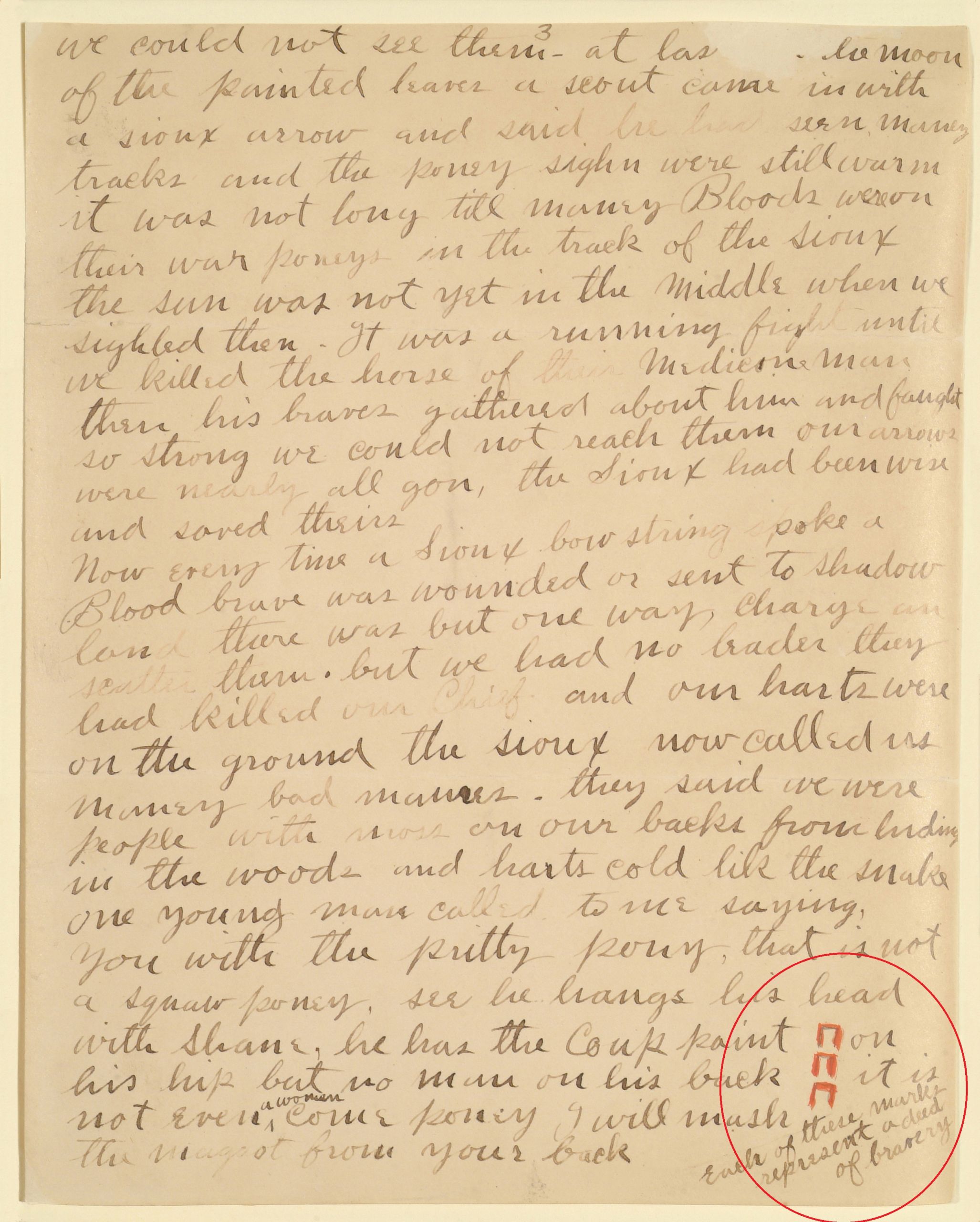

Page 3 of the letter

In the bottom corner of page three of his letter, Russell draws a column of three symbols with the note, “Each of these marks represent a deed of bravery.” How interesting! My colleague and I realized we had noticed those symbols earlier.

Let’s look back at the painting. Zoom in on the spotted horse in the front. There on his hind quarters is a similar symbol in the same sequence.

Detail of Counting Coup

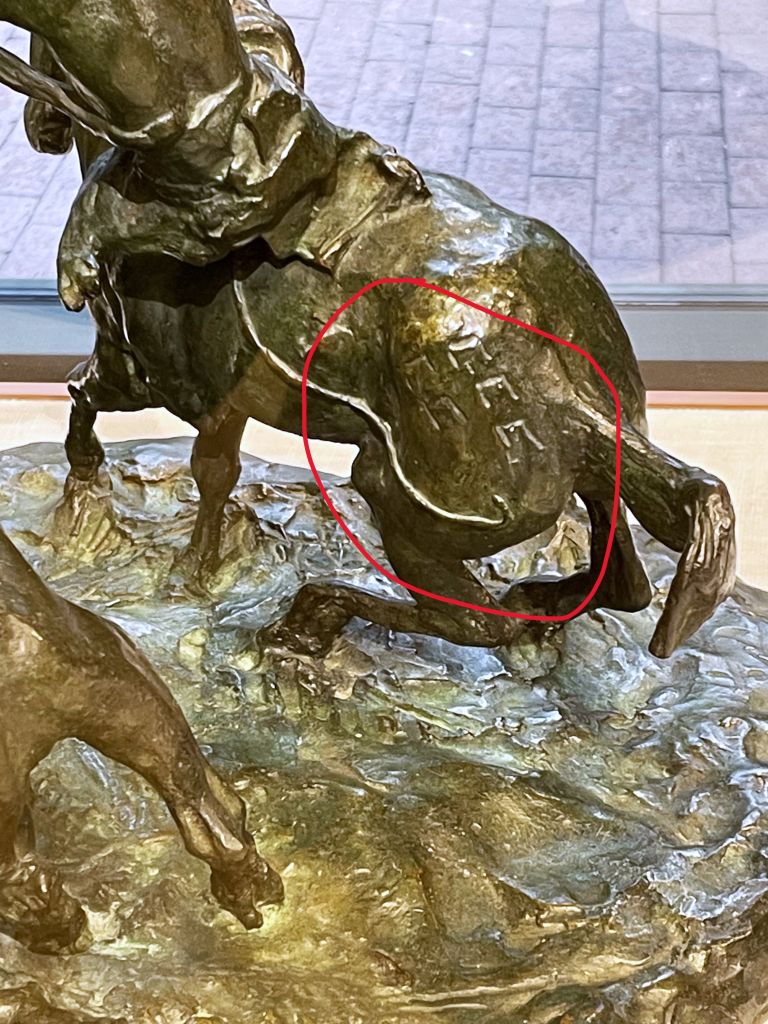

As we turned around, we saw one of Russell’s bronzes depicting similar subject matter. A few years after his painted composition, Russell pared down the battle to its essentials in a 1905 bronze sculpture. Here we zoom in to a Blackfoot [the Niitsitapi] warrior (holding the lance) and two Sioux [the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ] enemies engaged in close combat. (Fun fact: Russell also published a version of this story as “The War Scars of Medicine Whip” in Outing magazine in 1908.)

Charles M. Russell, Counting Coup, 1905, Roman Bronze Works, lost-wax process, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, Amon G. Carter Collection, 1961.116

Take a closer look at the shield the figure in the lower right is holding to protect himself. There, again, we see the same symbols as we found in the painting and the letter. What does it mean?

Detail of bronze sculpture Counting Coup

After a bit of research, we discovered that these symbols are meant to represent hoofprints. While each tribe may have had slightly different uses for the painted symbols, a general interpretation of the hoofprint symbol is that it specifies the number of times a rider had successfully stolen horses from an enemy.

And it turns out that Russell incorporated the hoofprint symbols in other artworks. On display in our front galleries are a couple more bronzes, including his Meat for Wild Men modeled in 1924. Russell’s largest work in bronze, this complex sculpture was composed of 57 separate molds!

The work is said to have been made after Russell visited the home of William W. Armstrong and viewed a cast of Frederic Remington’s bronze, The Stampede. Armstrong suggested to Russell that he do a large-scale buffalo hunt and several months later, Russell invited him over to see the plaster model.

The hunt featured here is known as a surround. The two mounted hunters crowd in on the running bison and force them into a confused frenzy. The crush of the herd causes one bull to pile on top of another at the front of the formation.

Charles M. Russell, Meat for Wild Men, 1924, Roman Bronze Works, lost-wax process, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, Amon G. Carter Collection, 1961.69

On the rear of the horse on the right side of the sculpture, something caught my eye. The hoofprint symbols! I counted five of them. And now we know that means that this rider was quite successful in capturing horses of his enemies.

The rewards of close looking at art!

Detail of sculpture Meat for Wild Men

Great article!

Thanks, Tim!