From Cowboy to Costume Designer: Joe De Yong and the Art Behind Hollywood’s Westerns

Before Clint Eastwood donned his poncho or John Wayne rode into the sunset, there was a young cowboy from Oklahoma with a sketchpad and a dream.

Joe De Yong’s life reads like a Hollywood script: cowboy, artist, silent film actor, survivor, and ultimately the bridge between Western art and the golden age of Western cinema. But unlike many stars on the silver screen, De Yong never craved the spotlight. Instead, he worked behind the scenes, shaping the imagery of the American West that generations of moviegoers have come to know and love.

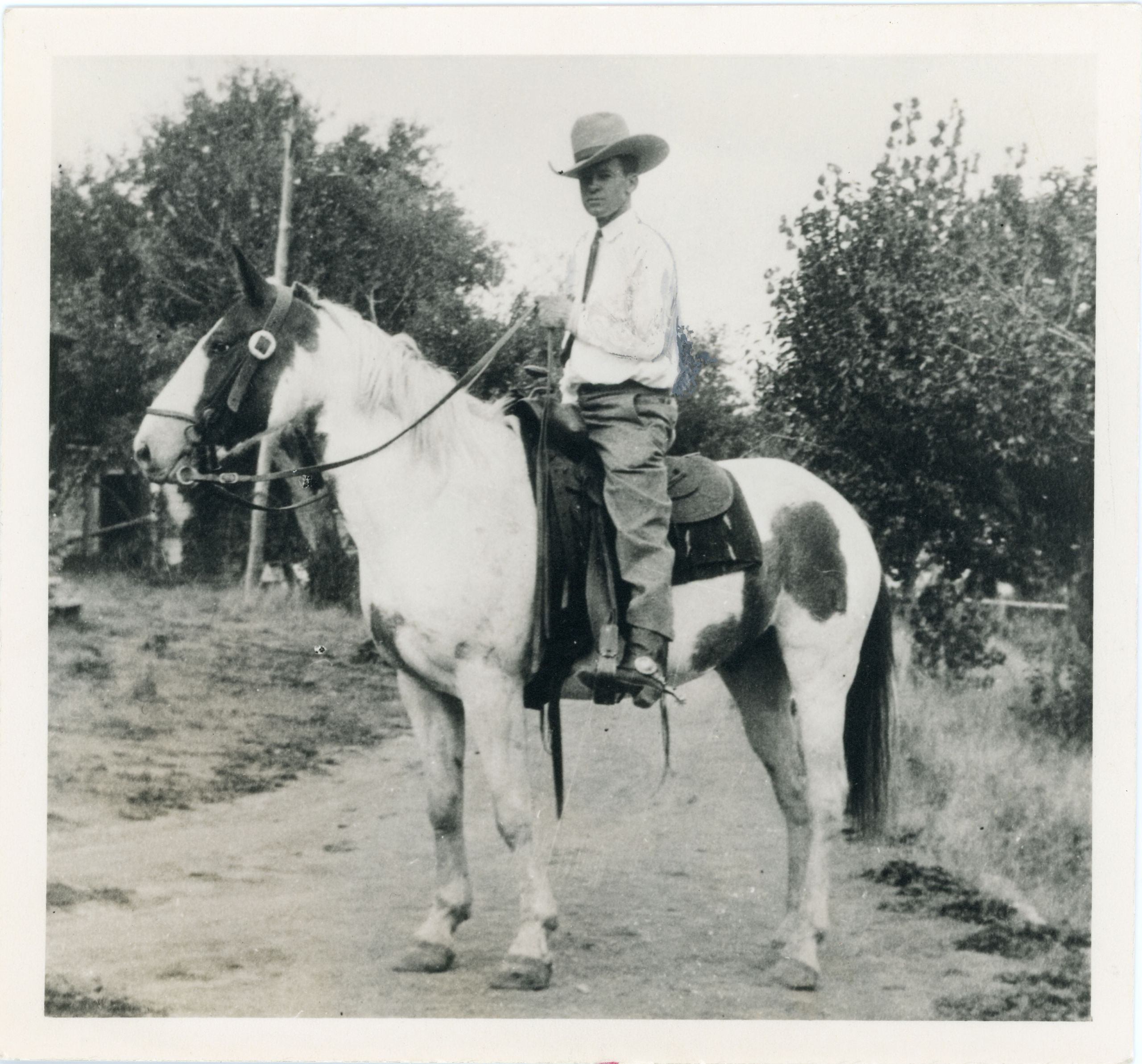

Joe De Yong, taken at Eaton’s ranch. Wolf, Wyoming – summer 1938. (Harry McCormick’s horse). Unknown photographer, 1938, photographic print. Joe De Yong Papers, Dickinson Research Center, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. 81.18.575.41.

A Deaf Cowboy’s Determined Path

De Yong’s story begins in the heartland, where the open plains of Oklahoma and the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair ignited his imagination. It was there that a young Joe first encountered the work of Charles M. Russell—The Cowboy Artist—whose depictions of frontier life blended gritty realism with romanticism.[1] That moment planted a seed that would later blossom into a lifelong pursuit of artistry, despite incredible odds.

After a brief stint acting in silent films with star cowboy Tom Mix, De Yong was struck with cerebral meningitis, a devastating illness that left him permanently deaf. Yet, his loss of hearing became a turning point. While recovering, he reached out to Russell with a letter and sketches, seeking mentorship. Not only did Russell reply, he welcomed De Yong into his home and heart, making him his only protégé.

For the last decade of Russell’s life, De Yong absorbed all he could, learning not just how to draw the West, but how to see it—its nuance, its culture, its stories.

Hollywood Calls

By 1925, De Yong had moved westward once again, this time to California. There, among fellow Western artists like Edward Borein and Maynard Dixon, he blended his deep knowledge of cowboy life and visual storytelling into a new role: Hollywood consultant. When famed director Cecil B. DeMille needed authenticity for his epic Union Pacific (1939), he turned to De Yong. (Fun fact: De Yong worked on this Texas post office mural while consulting on Union Pacific.) What followed was a prolific behind-the-scenes career designing costumes and advising on story accuracy for Western classics like The Plainsman (1937), Buffalo Bill (1944), and Red River (1948).

Joe De Yong, Concept drawing for Union Pacific, ca. 1939, watercolor, gouache, and pencil on illustration board, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, Oklahoma City, OK, 1980.18.166

His eye for detail was impeccable, rooted not in fantasy but in lived experience and the mentorship of Russell. Take, for example, his costume work for Buffalo Bill. De Yong used Russell’s painting Buffalo Bill’s Duel with Yellowhand as a reference. While the painting may not be 100% historically accurate, the association with the cowboy artist gave De Yong’s work a stamp of authenticity in Hollywood.

Today, we marvel at those Western films for their grandeur and grit. But many of the most iconic scenes owe their authenticity to a cowboy-turned-artist who knew what a real saddle felt like.

Western Art in Motion

The intersection of Western art and cinema isn’t just about aesthetics. It’s about cultural memory. And De Yong was a keeper of that memory, translating paint and canvas into celluloid myth.

Our current exhibit, The Cinematic West: The Art That Made the Movies, celebrates these unsung connections. Visitors can view De Yong’s costume sketches, see concept art like the unused buffalo hunt from Union Pacific, and even admire a cowboy hat he decorated for the elite riding group Rancheros Visitadores or “Visiting Ranchers”, etched with intricate designs using an electric wire.

Joe De Yong, Character study for Lewis from Shane, Watercolor and ink on illustration board, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, Oklahoma City, OK, 1980.18.169

Ashton Co., decoration by Joe De Yong, Rancheros Visitadores Hat, felt, grosgrain, and leather, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, Oklahoma City, OK, 1980.18.380

It’s a reminder that the Western isn’t just a genre, it’s a collaborative storytelling tradition. And Joe De Yong, with his sketchpad and spurs, was one of its earliest and most dedicated architects.

Timeless Influence

In today’s world of CGI and superhero blockbusters, De Yong’s story reminds us of the value of craftsmanship, research, and cultural respect. He didn’t just “make it look real.” He made it be real. At a time when authenticity and representation matter more than ever, his legacy feels especially vital.

Today, De Yong’s contributions offer more than just a glimpse into early Hollywood. They highlight the value of research, authenticity, and lived experience in storytelling. At a time when historical accuracy and cultural representation are increasingly important, his work stands as a reminder of the impact artists can have beyond the canvas. For those interested in learning more, De Yong’s personal papers are preserved at the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum, providing a rich archive of a life shaped by art, history, and the enduring spirit of the American West.

[1] Montana Cowboy Hall of Fame, https://montanacowboyfame.org/inductees/2024/5/joe-de-yong

Leave A Comment