*The following is part of a series of blog posts researched and written by Mark Clardy, SRM Docent and independent scholar.*

A Cowboy Chorale

Movement 3

Song of the New Hero

In this third Movement of our Cowboy Chorale we will explore the ascension of the lowly cowboy as the symbol of virtuous American manhood in the early twentieth century, and hear the songs (hymns?) of this unlikely apotheosis. We begin with the cowboy on stage, then follow his development as the star of the silver screen and the subject of Tin Pan Alley song writers. Two excellent references for more information on the cowboy themed music and stage productions of this era are: Talking Machine West: A History and Catalogue of Tin Pan Alley’s Western Recordings 1902-1918, by Michael A. Amundson (2017) and Early-Twentieth-Century Frontier Dramas on Broadway: Situating the Western Experience in Performing Arts, by Richard Wattenberg (2011).

Redemption of the Cowboy

Frederic Remington | The Cow Puncher | 1901 | Oil (black & white) on canvas | 28 7/8 inches x 19 inches

Until the first years of the twentieth century, the cowboy’s image was that of a lowlife ranch laborer. Since he was assumed to spend his paycheck and free time at a saloon or a brothel (or both), his life and exploits were not seen as suitable for contemporary song and stage. The cowboy might have remained in this unsung, drunken and diseased stereotype, except for a chance encounter between a famous artist and a famous writer at Yellowstone Park on September 8, 1893.

Until the first years of the twentieth century, the cowboy’s image was that of a lowlife ranch laborer. Since he was assumed to spend his paycheck and free time at a saloon or a brothel (or both), his life and exploits were not seen as suitable for contemporary song and stage. The cowboy might have remained in this unsung, drunken and diseased stereotype, except for a chance encounter between a famous artist and a famous writer at Yellowstone Park on September 8, 1893.

Frederic Remington and Owen Wister met entirely by accident that day at Yellowstone, and began a long personal and business relationship. Over the next several years, Wister wrote several articles about the West for Harper’s Magazine, which were illustrated by Remington, for example “The Evolution of the Cowpuncher” in September 1895. In their book Frederic Remington – Selected Letters (1988, p. 238), Allen P. and Marilyn D. Splete wrote that this article “epitomized their collaboration and conflict. Remington’s idea of the cowboy was quite different from Wister’s more noble figure.”

Wister and Remington continued to correspond and argue about the true nature of the cowboy for the next few years, with Wister taking the more heroic view. When Remington’s painting The Cow Puncher appeared in the September 14, 1901 issue of Collier’s, Owen Wister’s poem about the puncher conveyed his admiration:

No more he rides, yon waif of might,

His was the song the eagle sings,

Strong as the eagle’s his delight,

For like his rope, his heart had wings.

Both men published novels set in the West. Wister’s The Virginian (May 1902) was about a noble Wyoming cowboy from Virginia who, in the end, marries the local school teacher from Vermont. Remington’s John Ermine of the Yellowstone (November 1902) was about a white man raised from infancy by the Crow Indians. Both books were quickly adapted to stage and appeared at the Manhattan Theatre on Broadway. John Ermine opened on November 2, 1903, and The Virginian on January 5, 1904. The tragic ending of Remington’s story was changed in the stage production to a happier “boy–gets–girl” story, but Wister’s noble cowboy was still more popular with upper crust, theatre-going New Yorkers, and a new hero was born.

Both men published novels set in the West. Wister’s The Virginian (May 1902) was about a noble Wyoming cowboy from Virginia who, in the end, marries the local school teacher from Vermont. Remington’s John Ermine of the Yellowstone (November 1902) was about a white man raised from infancy by the Crow Indians. Both books were quickly adapted to stage and appeared at the Manhattan Theatre on Broadway. John Ermine opened on November 2, 1903, and The Virginian on January 5, 1904. The tragic ending of Remington’s story was changed in the stage production to a happier “boy–gets–girl” story, but Wister’s noble cowboy was still more popular with upper crust, theatre-going New Yorkers, and a new hero was born.

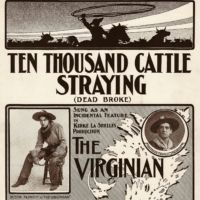

Neither production was billed as a musical. However, Owen Wister, who was a trained musician, also wrote a song for The Virginian play in 1904, which was “sung as an incidental feature”, or theme song, for the villainous character Trampas. Now take another look at Remington’s The Cow Puncher while listening to this song, “Ten Thousand Cattle Straying (Dead Broke)”. This may have been the earliest Broadway cowboy song, and possibly the precursor for Tin Pan Alley’s singing cowboys.

The Cowboy and the American Indian Maiden

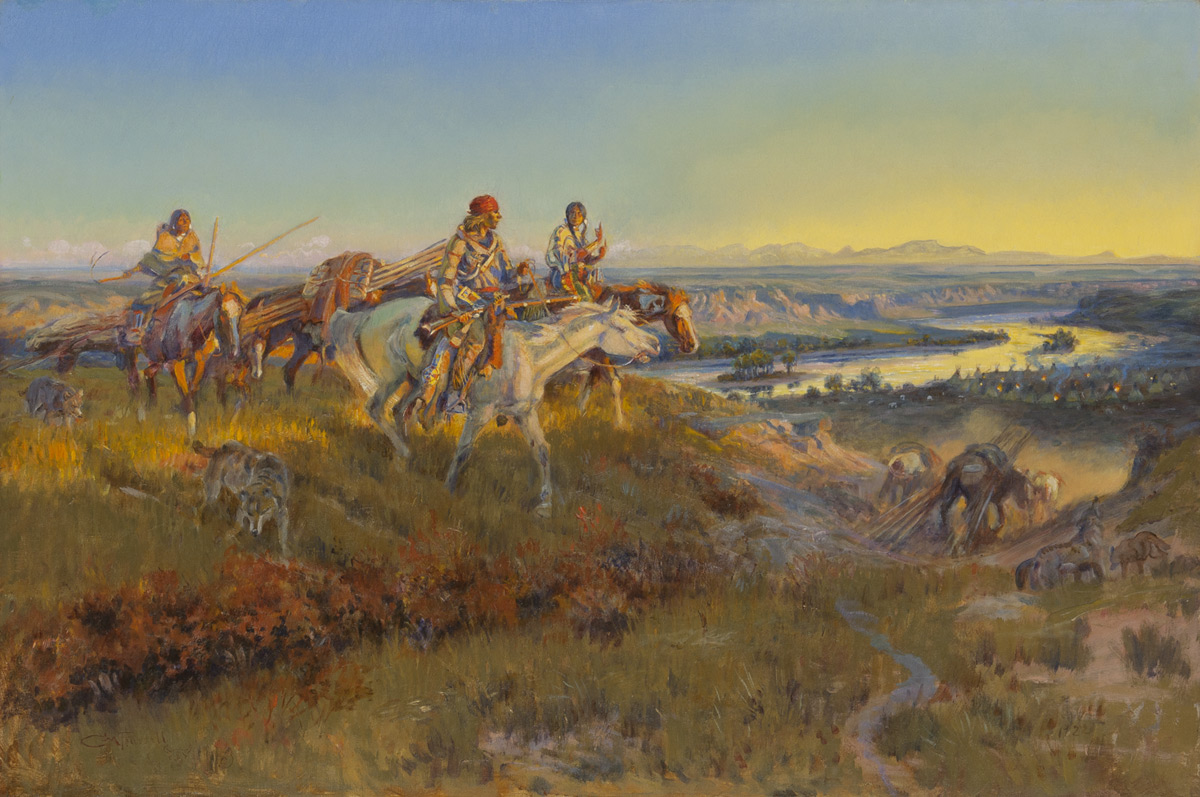

Charles M. Russell, When White Men Turn Red, c. 1922, Oil on canvas, 24 x 36 1/4 inches

White men on the frontier sometimes married American Indian women. As civilization advanced and the frontier receded, newcomers to the West began to call them the now-offensive name “squaw men”. Russell’s painting When White Men Turn Red depicts one such family in a bucolic setting which Russell considered to be a better way of life.

The play The Squaw Man by Edwin Milton Royle premiered at Wallack’s [second] Theater at 30th and Broadway on October 23, 1905, with William Faversham in the title role. (His wife Julie Opp Faversham adapted the play as a novel the following year.) The story has an English earl (played by Faversham) escaping a family scandal to the American frontier where he falls ill and is nursed to health by Nat-U-Ritch, daughter of the Ute chief. After they marry and have a son, news comes from England that he can return as the Earl, but he decides to send his son, instead. Unfortunately, Nat-U-Ritch becomes despondent and kills herself for a tragic ending.

“Nat-U-Ritch – An Indian Idyll” is an instrumental “Intermezzo” from the play for flute, cello and piano, composed by Theodore Bendix (1904). While listening to this piece, look again at Russell’s painting. What is the blond, Anglo man thinking? What do you think the woman next to him is saying? (By the way, do you see his red sash – like the one Russell wore?) What features do you hear in the music that were intended to convey an “Indian” sound?

“Nat-U-Ritch – An Indian Idyll” is an instrumental “Intermezzo” from the play for flute, cello and piano, composed by Theodore Bendix (1904). While listening to this piece, look again at Russell’s painting. What is the blond, Anglo man thinking? What do you think the woman next to him is saying? (By the way, do you see his red sash – like the one Russell wore?) What features do you hear in the music that were intended to convey an “Indian” sound?

The song writers of Tin Pan Alley were always tuned in to what would sell, and were well aware of what was popular on Broadway. Unfortunately, they weren’t very familiar with anything west of New Jersey, but who would care? A good song is a good song. Now, songs about American Indians had been popular since before Stephen Foster, but here was something NEW! We have the West, we have Native American maidens, and we just discovered cowboys; put them together and we have romance!

Two of the earliest songs about cowboys and Indigenous love interests were “Ogalalla – Indian Love Song” (1909) and “Laughing Eyes (My Omaha)” (1911). In addition to the “Indian” sounds, try to identify the music that signifies “cowboy.” What does the initial minor key in “Laughing Eyes” convey?

Buckers and Belles

Charles M. Russell, The Bucker, 1904, Watercolor, pencil & gouache on paper, 16 1/4 x 12 1/4 inches

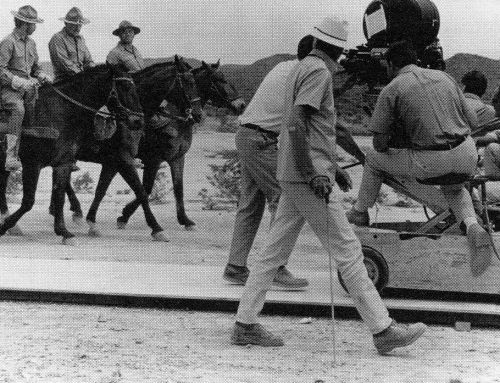

The image of a rider on a bucking bronco was one of Russell’s favorite motifs that he painted many times. The image also became firmly attached to the newly minted Western hero cowboy, and was adopted by the very first cowboy star of the fledgling film industry.

The image of a rider on a bucking bronco was one of Russell’s favorite motifs that he painted many times. The image also became firmly attached to the newly minted Western hero cowboy, and was adopted by the very first cowboy star of the fledgling film industry.

Maxwell Henry Aronson, a.k.a. Gilbert M. Anderson, a.k.a. “Broncho Billy” was 23 when he appeared in the silent film The Great Train Robbery (1903). He starred in his own series of 148 “Broncho Billy” silent films beginning in 1908. The song “Broncho Billy” (1909) was about the thrill of watching these very popular films in a theater.

Clearly, a bronco buster had to have his girl, and Tin Pan Alley songsters provided them. The cover art for “Cheyenne (Shy Ann)” (1906) is nothing like the story in the song about a shy cowgirl named Ann.

Here is a cylinder recording of “Cheyenne” (courtesy of Michael Amundson, Northern Arizona U.).

The cover art for “My Pony Boy” (1909) looks like it was taken from one of Russell’s bucker paintings. Several local cowgirls compete for the broncho boy’s affection, but seem to lose to a newcomer “fluffy ruffle girl” who wants to take him back to New York.

Cowboys at Work

Charles Schreyvogel, Attack on the Herd [Close Call], ca.1907, Oil on canvas, 26 1/8 inches x 34 1/4 inches

Several stories from the frontier tell about the survivors of Indian attacks on cattle herds, as depicted in Schreyvogel’s painting. Listen to the middle section of “Wild West (A Cowboy Indian Intermezzo)” (1908) for a shift that indicates an “Indian” presence.

Several stories from the frontier tell about the survivors of Indian attacks on cattle herds, as depicted in Schreyvogel’s painting. Listen to the middle section of “Wild West (A Cowboy Indian Intermezzo)” (1908) for a shift that indicates an “Indian” presence.

Roping the Renegade | Charles M. Russell | c. 1883 | Watercolor, pencil & gouache on paper | 12.5 x 16.625 inches

The cowboys throwing their lassos in the cover art for “Whoop ‘Er Up (March and Two-Step)” (1911) resemble the cowboys in Russell’s early painting.

The cowboys throwing their lassos in the cover art for “Whoop ‘Er Up (March and Two-Step)” (1911) resemble the cowboys in Russell’s early painting.

Ragtime and Blues on the Range

Three songs and three paintings finish out this “Song of the New Hero” Movement of our “Cowboy Chorale” series. These songs represent the convergence of the emerging sounds of Ragtime and Blues with the new Cowboy hero in the early twentieth century.

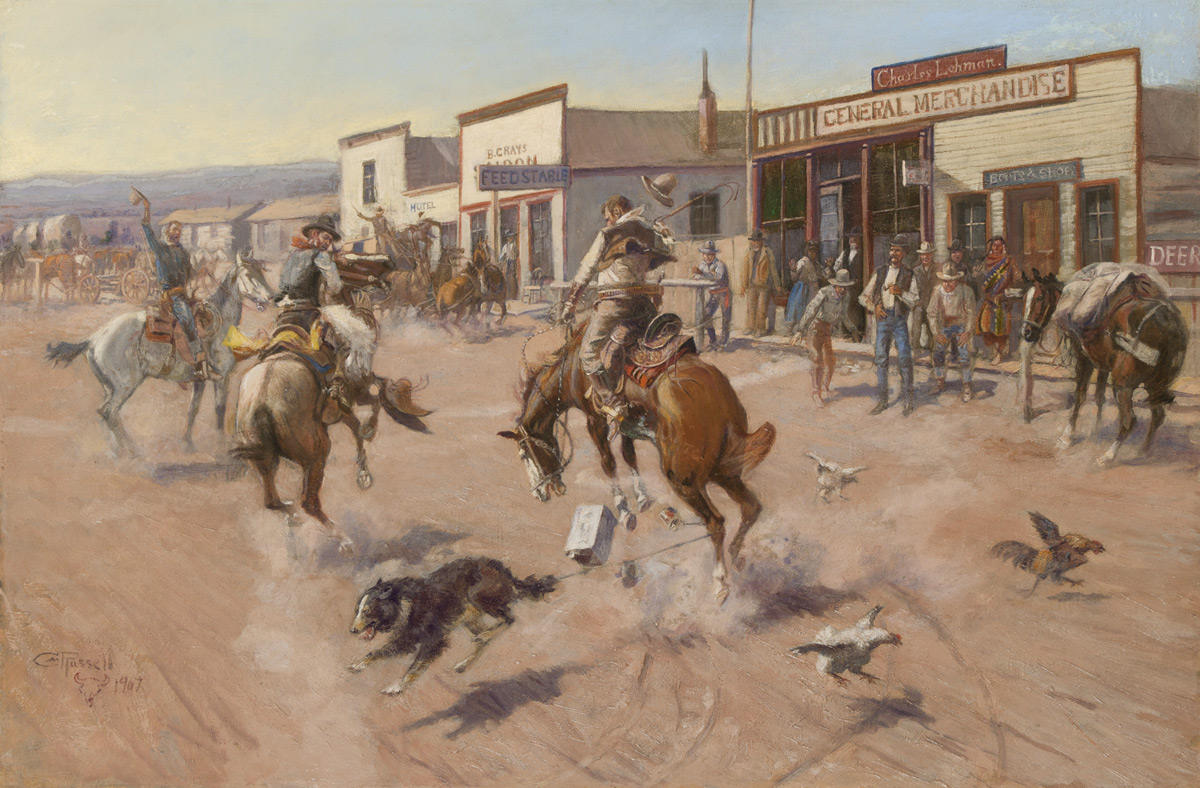

Charles M. Russell, Utica (A Quiet day in Utica), 1907, Oil on canvas, 24 1/8 x 36 1/8 inches

“The Cowboy Rag” (1911) This is another song about “a cute Fluffy Ruffles with a real Broadway Show” who wants to take ragtime banjo-playing cowboy Joe back with her to New York. The cover is reminiscent of Russell’s depiction of Utica, Montana.

“The Cowboy Rag” (1911) This is another song about “a cute Fluffy Ruffles with a real Broadway Show” who wants to take ragtime banjo-playing cowboy Joe back with her to New York. The cover is reminiscent of Russell’s depiction of Utica, Montana.

A Bad One | Charles M. Russell | 1912 | Pencil, watercolor and gouache on paper | 19.75 x 28.625 inches

“Ragtime Cowboy Joe” (1912) Joseph, the four year old nephew of one of the composers, was dressed in a cowboy costume one day when his uncle playfully introduced him as “Ragtime Cowboy Joe”, thus inspiring this well-known song made famous to a later generation of kids by Alvin and the Chipmunks.

“Ragtime Cowboy Joe” (1912) Joseph, the four year old nephew of one of the composers, was dressed in a cowboy costume one day when his uncle playfully introduced him as “Ragtime Cowboy Joe”, thus inspiring this well-known song made famous to a later generation of kids by Alvin and the Chipmunks.

Charles M. Russell, Roping, ca.1925–1926, Gouache on paper, 19 1/4 inches x 15 inches

“The Hooking Cow Blues (A Texas Jazz)” (1917) W. C. Handy, the self-described “Father of the Blues”, contributed the jazz and cattle bellowing sound effects to this early blues song, set “out in Texas with the hooking cows.”

“The Hooking Cow Blues (A Texas Jazz)” (1917) W. C. Handy, the self-described “Father of the Blues”, contributed the jazz and cattle bellowing sound effects to this early blues song, set “out in Texas with the hooking cows.”

This concludes our “Cowboy Chorale” movements. The Soundtrack of the American West continues next time with songs that the artists knew.

[…] banjo, plus harmonica). He saw Owen Wister’s play The Virginian in 1904 (see the previous blog, Song of the New Hero), but wasn’t especially impressed. He was dismayed that the play featured Wister’s […]