Our current exhibit, In A Different Light: Winslow Homer & Frederic Remington, explores some of the comparisons in the careers of these two iconic American artists. One of those parallels is that both Homer & Remington served as artist war correspondents: Homer in the Civil War and Remington in the Indian Wars in the Southwest and the Spanish American War in Cuba. The exposure to the realities of war made a lasting impression on both men.

At the outset of the Civil War, Harper’s dispatched Homer to the frontlines in Virginia in 1861 to capture life on the battlefield. On assignment, he sketched both the quiet and chaotic moments, battle scenes and camp life.

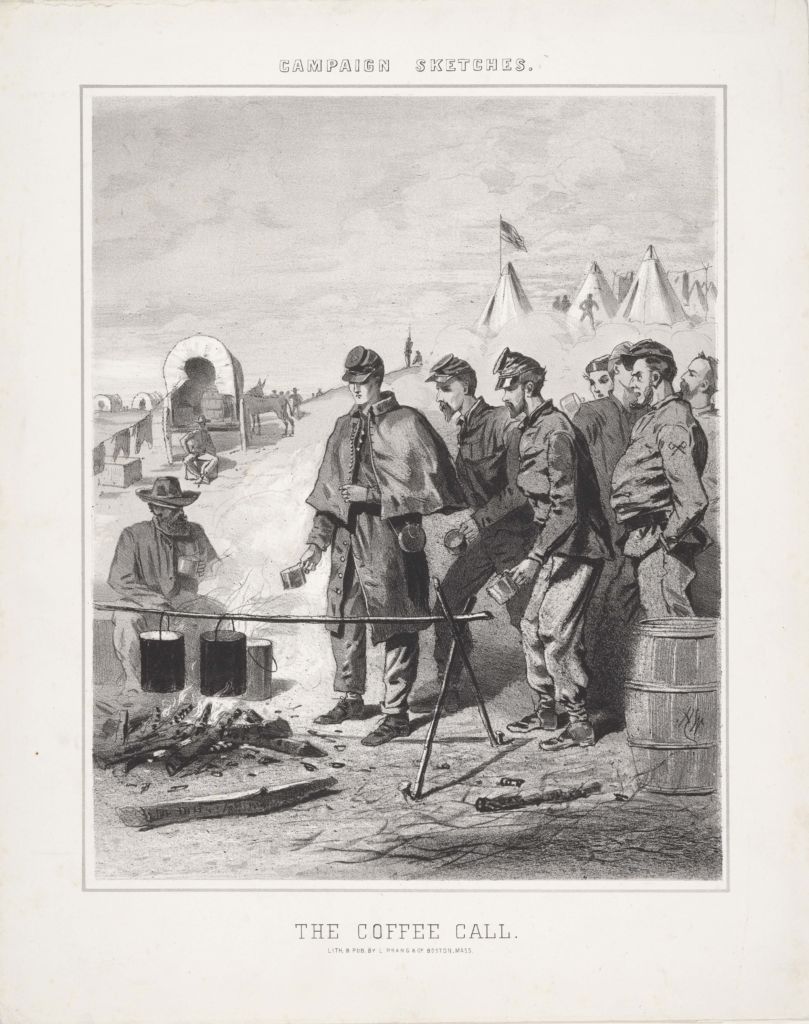

Included in our current exhibit is one of six prints Homer made as a commercial venture under the title Campaign Sketches in 1863.

Winslow Homer (1836-1910), The Coffee Call. [from “Campaign Sketches”], 1863, Lithograph, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, 1983.50

Although Homer’s Campaign Sketches deliberately avoid the grim reality of the war, Homer’s images of the conflict were soon to change. Friends and family noticed how Homer had suffered as much as the soldiers he had accompanied. His mother had observed that Homer, “…came home so changed that his best friends did not know him.”

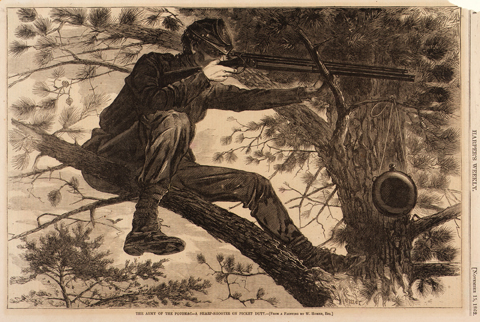

His breakthrough image, The Army of the Potomac — A Sharpshooter on Picket Duty, appeared in Harper’s Weekly in November of 1862. With its close-up view of a sniper set amidst the camouflage of a pine tree, the action is implied with its intended target out of view. Although he found success with this important composition (which he also used as the subject of his first oil painting), Homer expressed his displeasure with the role of the sharpshooter in war, writing that it was, “as near murder as anything I could ever think of in the army and I always had a horror of that branch of the service.”

Winslow Homer, The Army of the Potomac–A Sharp-Shooter on Picket Duty, 1862, wood engraving on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of International Business Machines Corporation, 1966.48.81

Remington, too, witnessed the realities of war first-hand. His first assignment for Harper’s came in 1886 when he was assigned to a cavalry regiment in search of Geronimo in the American Southwest. Being enamored with the military due to his father’s service in the Civil War, Remington jumped at the chance to document the glories of battle when the U.S. was drawn into the Cuban revolt against Spain in 1898. The artist expected to record a heroic cavalry charge into battle but was quickly disillusioned by the tactics of guerilla warfare and an unseen enemy.

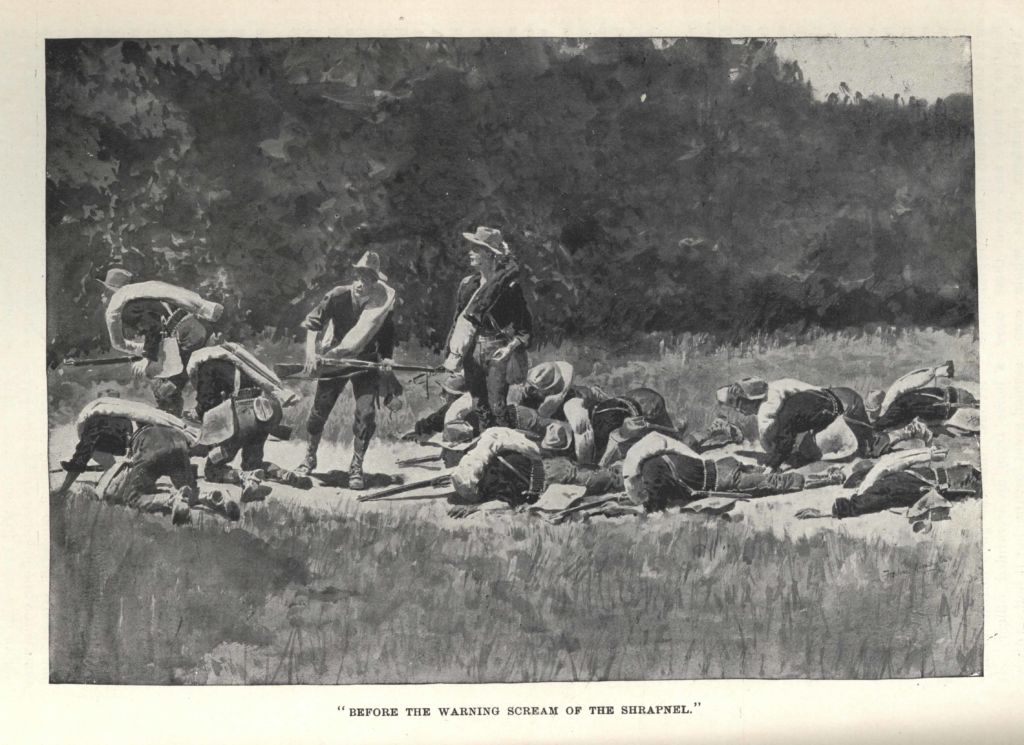

Frederic Remington, Before the Warning Scream of the Shrapnel, from Harper’s Monthly , November 1898, p.965, Harper’s Magazine

Haunted by this experience of modern warfare, Remington began to explore the effects of what he had seen. His reports and illustrations upon his return focused not on heroic generals but on the troops, as in his 1898 Before the Warning Scream of the Shrapnel. Remington saw how only the “scream” of shrapnel signaled the approach of an unseen enemy.

Having confronted the uncertainty of warfare in the rainforests of Cuba, Remington’s zeal for combat quickly subsided. Some scholars believe that the unknown danger and anxious anticipation Remington experienced in the Spanish American War lingered with the artist and revealed itself metaphorically in the nocturnes produced in the final decade of his life.

Interesting that this painting had no definitive title and now may be the same as a painting that was well know in that records of it sale were reported. I has thought of it as an authentic depiction of Indian life at the time it was done (ca. 1880) when native Americans were on reservations and were no longer living the traditional life of nomadic hunter/gatherers but were having to adapt and adopt western ways including dress, food, etc.

[…] until he viewed soldiers in action (and inaction) during the Spanish-American War in 1898 (see Illustrating Disillusions of War). He did, however continue to paint scenes of soldiers set in previous decades in danger on the […]