One of the similarities between Frederic Remington and Winslow Homer as demonstrated through our current exhibit, In a Different Light: Winslow Homer & Frederic Remington, is that both artists made their start as illustrators working for the popular magazines of the period (Harper’s Weekly, Scribner’s Monthly, etc). One of their key assignments was as war correspondents. Remington focused on the American Indian Wars in the Southwest and later the Spanish American War in Cuba. Being from an earlier generation, Homer focused on the American Civil War.

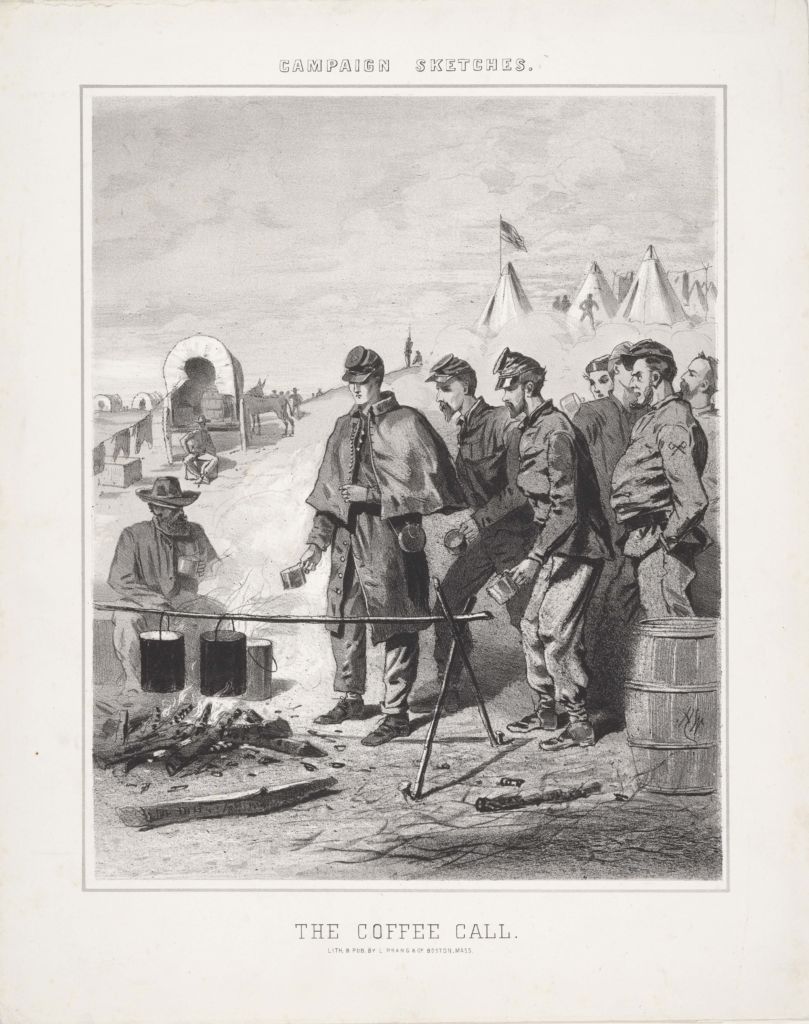

In 1863, Homer partnered with Boston publisher Louis Prang (who is sometimes referred to as the “father of the American Christmas card”) in a commercial lithography venture. The result was Campaign Sketches, a series of 6 scenes plus a cover that sold for $1.50. Although depicting life of the military during the Civil War, the images of these lithographs avoided scenes of combat or death and instead revealed the tedium of day-to-day life in camp. One such example is Homer’s The Coffee Call, which depicts Union soldiers lining up somewhat impatiently for coffee while waiting for the next battle.

Winslow Homer (1836-1910), The Coffee Call. [from “Campaign Sketches”], 1863, Lithograph, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, 1983.50

Sharps Carbine, Springfield Armory Museum

Jon Grisban, a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, noted that the word coffee was used more often in Civil War soldiers’ diaries and letters home than words like “war,” “slavery,” or “Lincoln.” One soldier, with some surprise that he was still alive, wrote home that “what keeps me alive must be the coffee.”

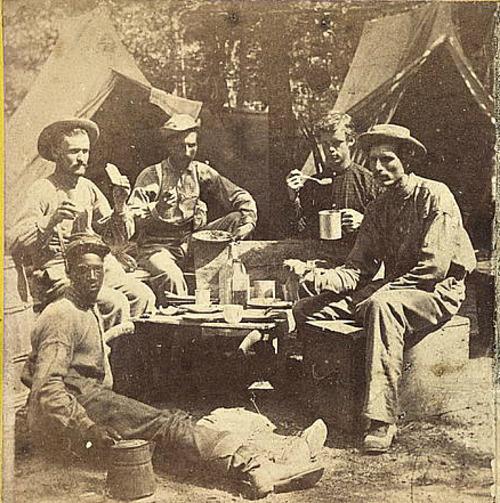

Union soldiers at mealtime, Collection of the Library of Congress.

While diaries and letters included remarks from Union soldiers on how often they made coffee, Confederate soldiers commented on the lack of coffee. In 1863, one Confederate soldier wrote “We are reduced to quarter rations and no coffee. And nobody can soldier without coffee.” Union soldiers had blocked Southern ports so Confederate soldiers had to get creative with their coffee substitutes based on what was around and could be roasted in the field, which included chicory, acorns, dandelions, rye, peanuts, and peas. They were desperate for something warm and brown. Their substitute coffee contained no caffeine, but distressed soldiers claimed to love it.

Pickets Making Coffee by Mathew Brady, Collection of the National Archives and Records Administration

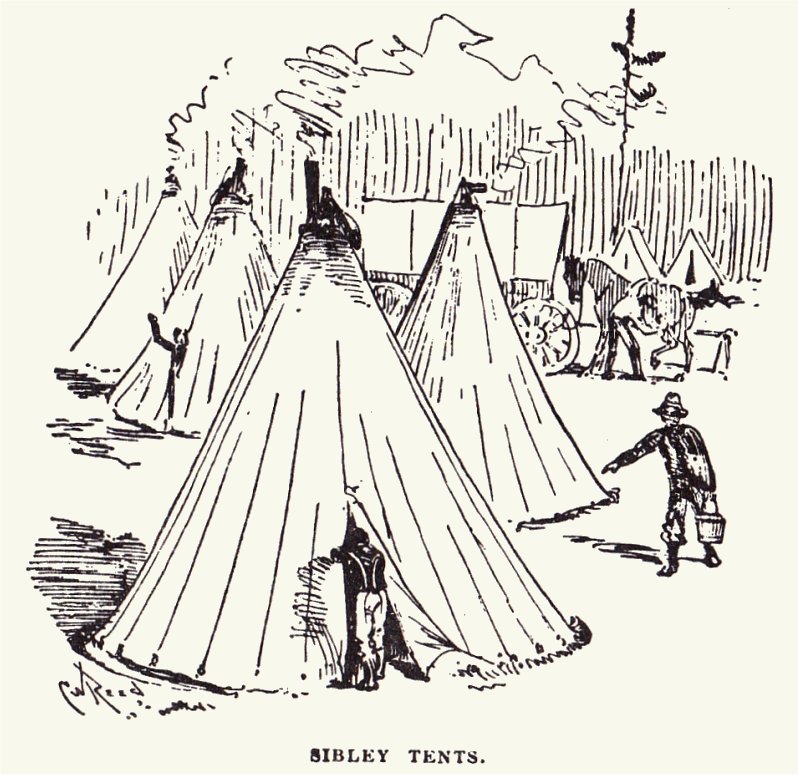

Take another look at Homer’s lithograph The Coffee Call. In the distant background, one can see tents that resemble teepees. The style of tent was designed in 1857 by Henry Sibley, a West Point graduate who took inspiration from the Native American teepee after visiting a Comanche village while stationed at the Texas frontier.

The Sibley tent was 18 feet in diameter at the base and reached 12 feet high, with room enough fit a dozen men comfortably. Unlike a Plains Indian teepee, in which animal hides were stretched over 12 poles, the Sibley tent was made from canvas and had one center pole.

In 1858, the Department of War agreed to pay Sibley $5 for every tent made. However, after Sibley decided to join the Confederate Army after the outbreak of the Civil War, he never received a dime. The Union Army produced and used nearly 44,000 Sibley tents during the war. Expensive and bulky, the Sibley tent went out of field service in 1862.

A group of Union soldiers belonging to Company G of the 71st New York Infantry pose for the camera in front of a Sibley tent in 1861.

We invite you to take a closer look at Homer’s The Coffee Call, along with the rest of the exhibit, by touring the museum virtually with our 360-degree virtual tour.

Fascinating! I found it surprising to read the word “coffee” appeared more in soldiers’ correspondence than the words “Lincoln”, “war” and “slavery”.

Yes! I thought that was fascinating, too. It’s interesting to hear what was most on the minds of soldiers: coffee, coffee, coffee!

[…] Nobody Can Soldier Without Coffee […]

[…] the Civil War. In 1865 at the end of the Civil War, a Union cavalryman named Ebenezer Nelson Gilpin wrote in his diary, “Nobody can soldier without coffee,” and we couldn’t […]