Remington depicts “thunder fighters” of the Sioux Nation not only braving a storm, but braving their own fears to chase off the big black thunder bird whose beating wings filled the air with roaring. The painting was originally intended as an illustration in the 1892 edition of Francis Parkman’s The Oregon Trail.

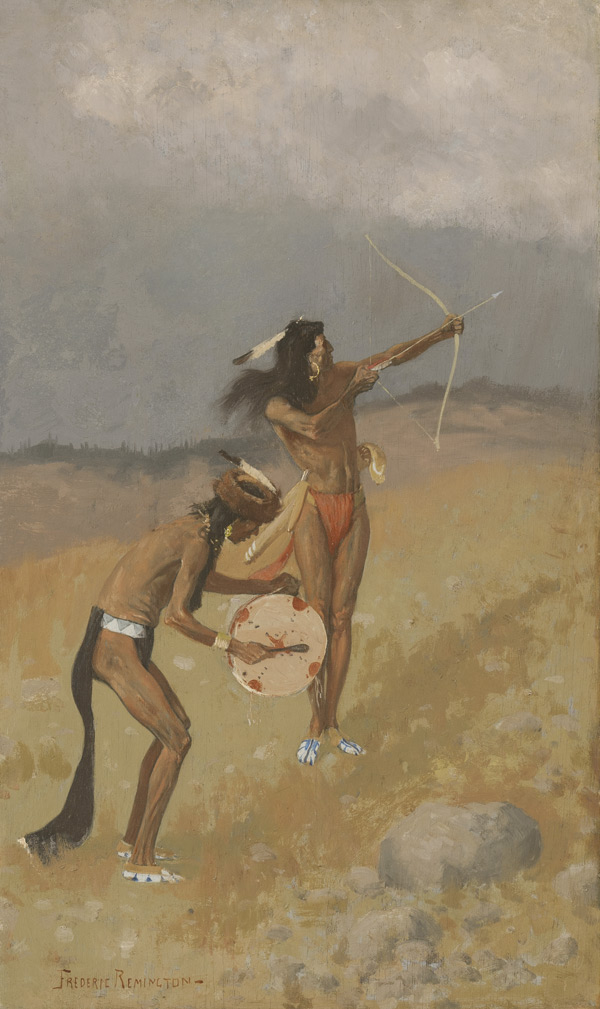

Frederic Remington | The Thunder-Fighters Would take Their Bows and Arrows, Their Guns, Their Magic Drum | 1892 | Oil on wood panel | 30 inches x 18 inches

Francis Parkman (1823-1893) was born into a well-to-do Boston family. In April of 1846, just out of Harvard Law School at age 23, Parkman and his college friend and relative, Quincy Shaw, departed from Westport, Missouri on a journey of western travel and adventure. Despite being in poor health (dysentery, cramps and dizziness – oh my!) for much of the nearly 6-month journey, Parkman traveled 2,000 miles of prairies, deserts and mountains, coming into contact with emigrant trails. The Oregon Trail is the author’s reflection (and, in some cases, exaggeration) of his travels.

The first edition was published in 1849. For his 4th edition, Parkman asked Frederic Remington to illustrate its pages. Remington accepted.

My dear sir: As you know, I am to illustrate your “Oregon Trail.” You paint men very vividly with your words and I imagine I can almost see your people. I shall never be able to fill your mind’s eye but if I manage to symbolize the period, I shall be content. Trusting that I may hear from you shortly, I have the honor to be very respectfully yours, Frederic Remington. (January 5, 1892)

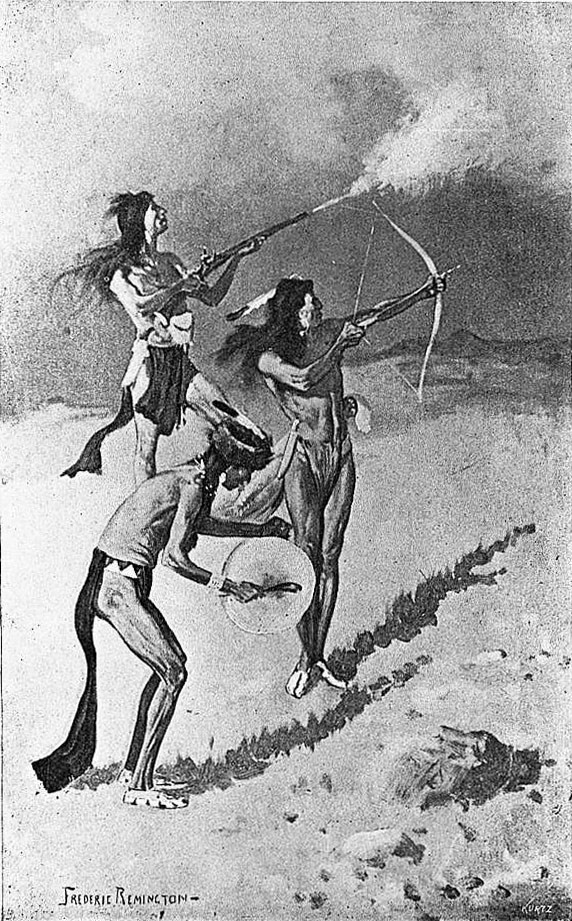

Frederic Remington | The Thunder-Fighters Would Take Their Bows and Arrows, Their Guns, Their Magic Drum | 1892 | line engraving | Parkman, Francis. The Oregon Trail, 1892, p. 112

Remington’s image illustrates a scene described in Chapter 14, “The Ogillallah Village.” Parkman and his travel companion, Raymond, enter an Ogallala Sioux village, where the two men meet an acquaintance named Reynal, a French Indian trader. Reynal serves as interpreter between the two men and the members of the village. Parkman and Raymond, guests of the village, have been moving from lodge to lodge to taste the foods their hosts set before them. After a meal of boiled buffalo meat and other foods, a thunderstorm that had been threatening strikes, which spurs Parkman to ask:

“What is it?” said I, “that makes the thunder?”

“It’s my belief,” said Reynal, “that it’s a big stone rolling over the sky.”

“Very likely,” I replied; “but I want to know what the Indians think about it.”

So he interpreted my question, which produced some debate. There was a difference of opinion. At last old Mene-Seela, or Red-Water, who sat by himself at one side, looked up with his withered face, and said he had always known what the thunder was. It was a great black bird; and once he had seen it, in a dream, swooping down from the Black Hills, with its loud-roaring wings; and when it flapped them over a lake, they struck lightning from the water.

“The thunder is bad,” said another old man, who sat muffled in his buffalo-robe; “he killed my brother last summer.”

Reynal, at my request, asked for an explanation; but the old man remained doggedly silent and would not look up. Some time after, I learned how the accident occurred. The man who was killed belonged to an association which, among other mystic functions, claimed the exclusive power and privilege of fighting the thunder. Whenever a storm which they wished to avert was threatening, the thunder-fighters would take their bows and arrows, their guns, their magic drum, and a sort of whistle made out of the wing-bone of the war-eagle, and, thus equipped, run out and fire at the rising cloud, whooping, yelling, whistling, and beating their drum to frighten it down again. One afternoon a heavy black cloud was coming up, and they repaired to the top of a hill, where they brought all their magic artillery into play against it. But the undaunted thunder, refusing to be terrified, darted out a bright flash, which struck one of the party dead as he was in the very act of shaking his long iron-pointed lance against it. The rest scattered and ran, yelling in an ecstasy of superstitious terror, back to their lodges.

Compare the illustration with the painting as it exists today at the museum. Do you notice how they differ?

When you visit the painting in our galleries, you’ll see that Remington eliminated the figure in the background, softened the shadows and added a design on the drum, which resembles a drum in the Remington Studio Collection at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West.

Crow Drum | ca. 1880 | pigment, wood, rawhide, lacing, string | Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming

The original painting showed the three figures shooting and beating the drum to frighten the cloud down to the earth. In the first version, Remington included a third man standing behind the other two discharged his musket into the sky. Later, as seen today, the artist painted over the third figure, simplifying the composition.

This was a very interested read. I truly enjoyed it. Thanks

[…] Their Guns, Their Magic Drum. We explored the mystery surrounding this artwork in an earlier blog post. Fortunately, we have great detectives in the way of art conservators to help us. X-rays and […]