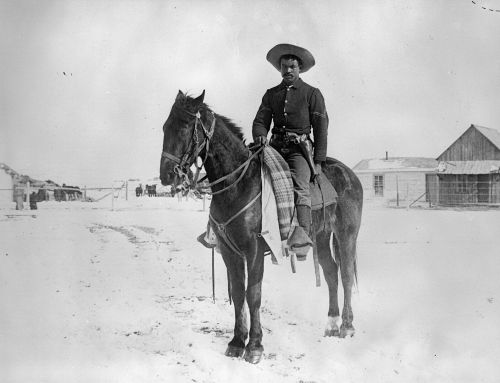

What do we see when we picture the American West? Perhaps Native women, elderly Indigenous men, or Anglo cowboys. Commonly imagined through art and film, these have been the consistent images of the American West that are still accepted to this day and that, until recently, very few people have questioned. This imagined West was very real for generations of people and remains the way that, for many people, we picture this place.

Another way the “Old West” is imagined and imaged is through erasure; a time and place that is supported by those we do not see.

In a 1938 interview, Agnes Walker (born in 1862) of Bartlesville, Oklahoma, shared that her parents were formerly enslaved people. Clem Rogers, father of the now-famous Will Rogers, was the master of Agnes’ father and her later-to-be husband, Dan Walker, who worked as a cowboy on the Rogers ranch. Agnes said that Dan was the best roper and rider on the ranch. She noticed that Will Rogers was always happy when he was with Dan. When Dan was teaching his 3 young children to ride and rope, young Willy learned, too, becoming a talented performer later known as “Oklahoma’s Favorite Son.” Will Rogers was known for his roping skills, but we do not question how these skills were learned. The general public never learns about Dan.

Will Rogers caricature on a print advertisement for the film Down to Earth, from The Film Daily, 1932, Public Domain

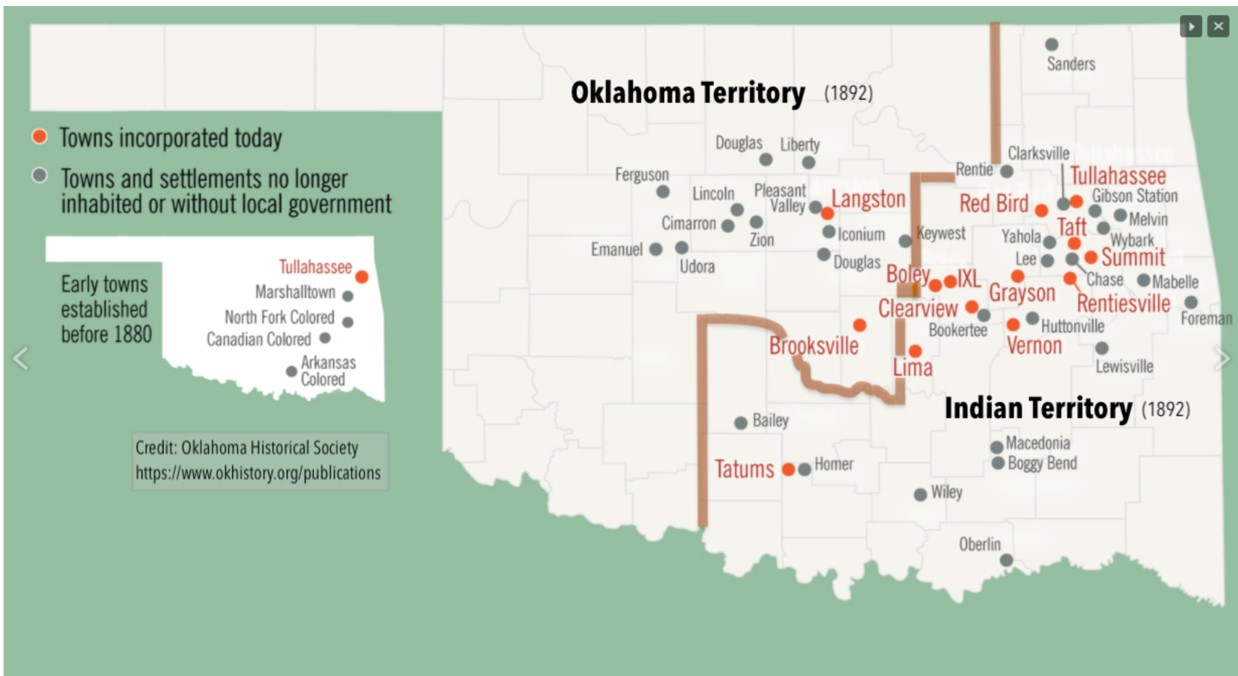

Black people traveling throughout the American West since the 15th century often served as translators, guides or cultural brokers for explorers and traders. As time progressed, more permanent settlement of Black populations developed west of the Mississippi so that by 1840s nearly 9,000 people of African descent were living in Indian territory (today known as Oklahoma), for example. Many of the new settlers came primarily from southeastern US, mostly enslaved, often uprooted with their Indigenous masters and relocated to assigned lands during the Trail of Tears.

Near the end of the Reconstruction era, many other Black people living in the southern states considered relocating to have an opportunity at freedom and liberation, resulting in the migration of Black populations to the Great Plains region. The Homestead Act of 1862 had encouraged settlement of “new territories” (at the expense of the Indigenous people currently living there) to create family farms. The federal government gave 160 public land for free after applicants had submitted a filing fee and completed several requirements such as living on their claim for 3-5 years, building a residence, and making improvements on the land. The unrestrictive eligibility requirements opened up land ownership to a large swath of the public, including many formerly enslaved Black people. According to published records, between 1880-1900 the states of Kansas, Nebraska, Texas and Oklahoma witnessed an increase of African Americans between 50% to 150%.

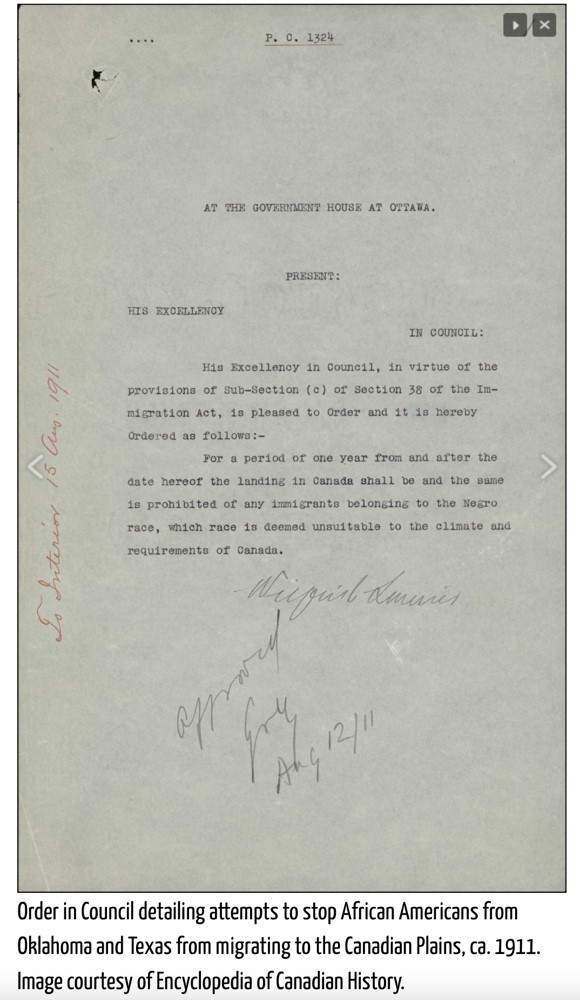

In contrast to the propaganda promising a comfortable life or an agrarian utopia, many Black citizens in the Great Plains found little difference in their status west of the Mississippi River. National papers reported violent confrontations or how Black families were forced off their lands. Discrimination was experienced north of the border, as well. Between 1909-1911, a large movement of African Americans from Oklahoma migrated to the prairies of Alberta, Canada after the passage of the Dominion Lands Act (similarly to US, Canada was allotting out land from the First Nation’s people to new settlers). But the federal government of Canada, recognizing this influx of Black settlers, quickly shut down the program, arguing that the weather was “unsuitable” for them.

Learn more about Black homesteaders in the American West from a recording of a recent public lecture, Westside Stories: Interpreting African American Migration & Settlement in the Western US, presented by Dr. Kalenda Eaton, Associate Professor at University of Oklahoma and Director of Oklahoma Research for the Black Homesteader Project.

[…] in the southern states considered relocating to have an opportunity at freedom and liberation, resulting in the migration of Black populations to the Great Plains region. The Homestead Act of 1862 had encouraged settlement of “new territories” (at the expense of […]