This month marks the opening of our new focus exhibit from our “Guest of Honor” series entitled Frederic Remington: Altered States. This exhibit brings together a small grouping of Remington’s works, including two rarely seen paintings from the Museum’s permanent collection, as well as bronzes and books from private collections. Altered States not only highlight’s Remington’s career as an illustrator, but it also examines the various issues surrounding the authenticity of a work of art.

Let’s first look at alterations to artworks made by the artist’s hand. The exhibit features two versions of the same Remington bronze, The Rattlesnake. In this sculpture, Remington depicts a rider and his horse shying away from a rattlesnake on the ground. The scene is filled with unrestrained action. Three years and eleven castings after his first cast of The Rattlesnake, Remington reworked the design and the resulting bronze exhibited some different details. First there are the structural alterations, with the overall sculpture being 3 inches taller than the first version and with a smaller base. Changes to the model included tucking the horse’s forelegs and straightening his rear legs which increased the tension and thrusted the rider forward. While viewing the two bronzes displayed side by side in the gallery, make note of the alterations of the rider’s gear in the second version of the sculpture. Even the color of the patina of the bronze is different.

The Rattlesnake [first version] | Copyrighted January 18, 1905 | Roman Bronze Works cast #5, 1906 | Private Collection

The Rattlesnake | Copyrighted 1905 | Roman Bronze Works cast #19, 1910 | Private Collection

Frederic Remington | The Thunder-Fighters Would take Their Bows and Arrows, Their Guns, Their Magic Drum | 1892 | Oil on wood panel | 30 inches x 18 inches

Another example of alterations to an artwork by the artist himself is the SRM painting The Thunder-Fighters Would take Their Bows and Arrows, Their Guns, Their Magic Drum. We explored the mystery surrounding this artwork in an earlier blog post. Fortunately, we have great detectives in the way of art conservators to help us. X-rays and infrared photography of the painting revealed the hidden third figure that Remington had over painted. Exactly why Remington chose to alter the composition from the published illustration remains a mystery.

X-ray of Remington’s Thunder Fighters with 3rd figure circled

Sometimes artists make changes to their artwork, but sometimes alterations are made by those other than the artist, which raises various questions about authenticity. Take for example the SRM painting He Rushed the Pony Right to the Barricade. Remington originally painted this work in black-and-white for an illustration that was published in his novel, The Way of an Indian (a copy of which is on display in the exhibit). The Museum has other black-and-white paintings in the collection by Remington as well. What makes this work stand out? At some point, someone painted over He Rushed the Pony Right to the Barricade, resulting in a vibrantly hued composition. But who did it? This sounds like another excellent case for art conservators, a.k.a. the detectives! An analysis at a research lab revealed that a layer of dirt separated two layers of paint, indicating that several years had passed between the applications. Furthermore, analysis of the top, colored layer determined that this paint was not produced until over two decades after Remington’s death. Ah ha! Twas not an alteration by the artist’s hand. Someone with fraudulent intentions has compromised the work.

He Rushed the Pony Right to the Barricade | ca. 1900 | Oil on canvas

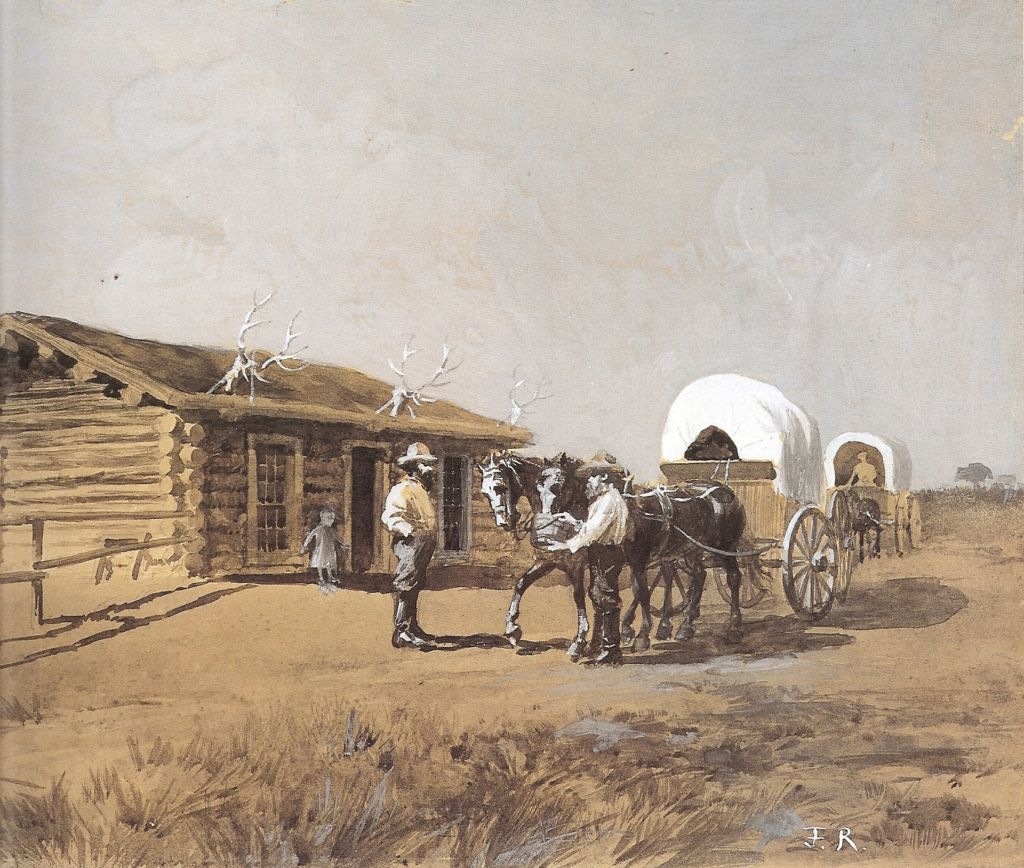

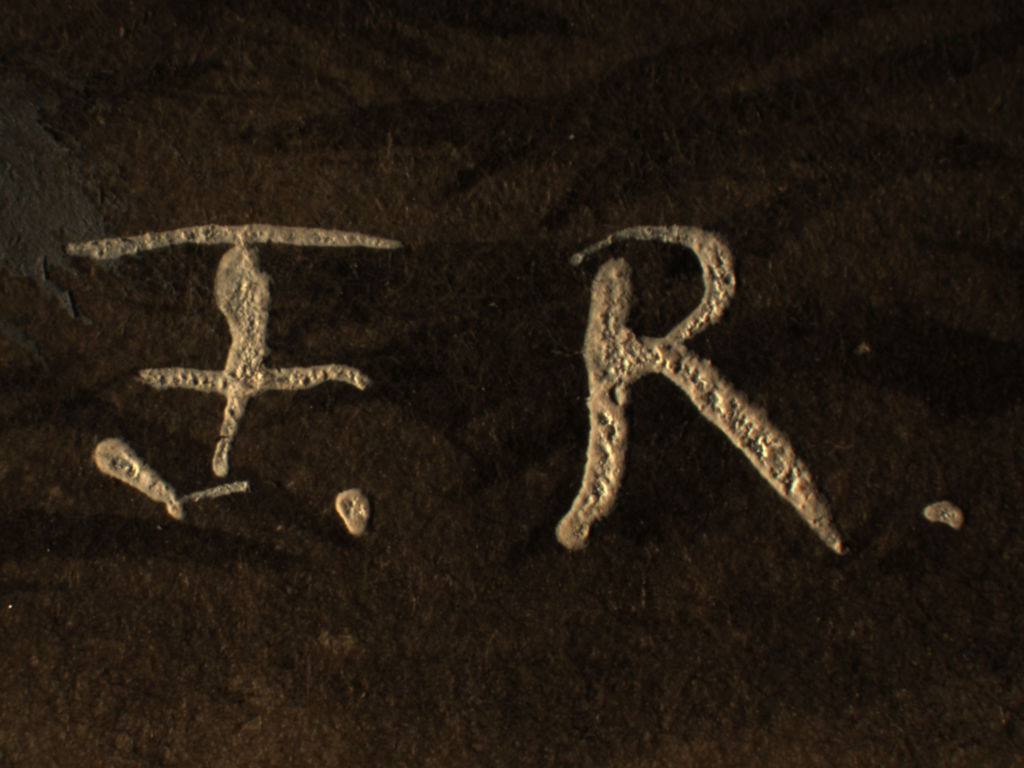

The ultimate Remington mystery involves a small work on paper entitled The Way Post. The simple watercolor study could perhaps be a product of Remington’s first trip West in 1881, a brief period in which the young artist signed his works with his initials, “F.R,” though he rarely used it as his signature after that year. Despite those details, it is difficult to attribute this work to Remington with certainty.

The Way Post | attributed to Frederic Remington | ca. 1881 | Watercolor and gouache on paper

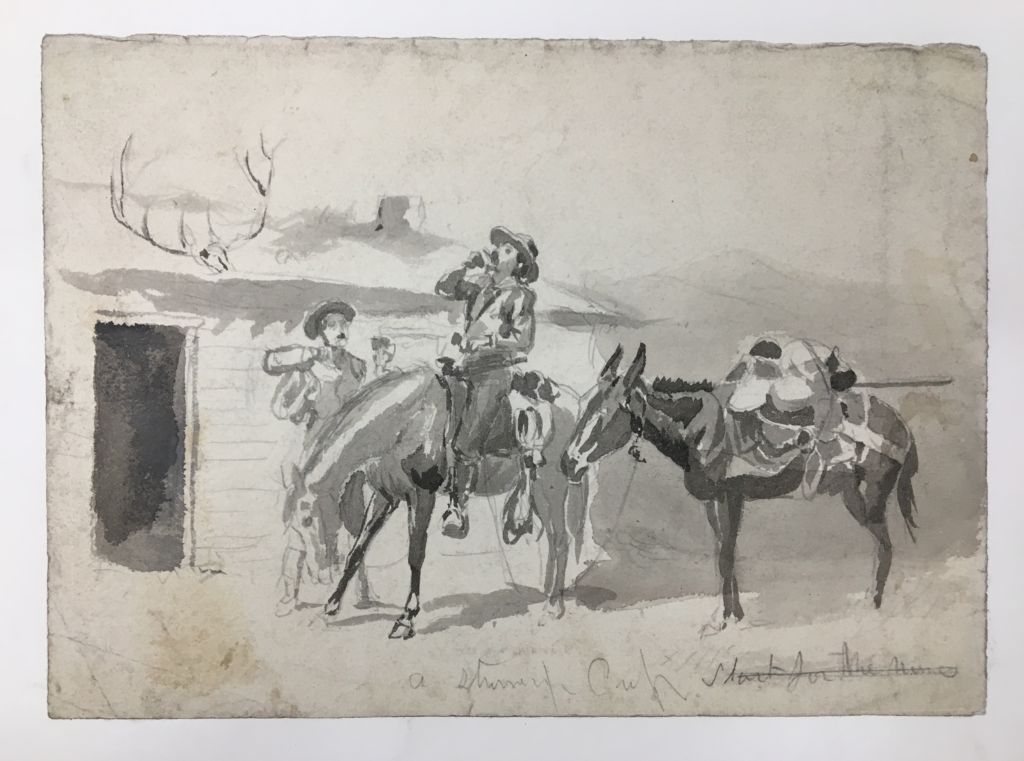

In fact, the work is reminiscent of another Western illustrator of the same era, William de la Montagne Cary (1840-1922). The Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, OK houses a collection of Cary’s works, including a watercolor sketch of comparable size, The Strong Cup.

William de la Montagne (1840-1922), A Strong Cup, Collection of the Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma

With so many questions circulating around an artwork like this, who are you going to call? The art conservators! Conservation staff at the Kimbell Art Museum conducted studies on the work from the Museum’s collection. While infrared reflectography (a non-invasive method of looking through paint layers) did not real any pentimenti, or artist changes, examination under the microscope revealed that the signature initials were painted with a bulkier, more granular white paint than the artist used for highlights in the rest of the work. Likewise, the initials appear raised from the surface, not integrated. All of this suggests that the signature was a later addition. Did Remington add his signature at a later date? Is The Way Post the work of another artist? Do we have a forgery on our hands? This mystery remains unsolved.

Detail of Remington’s signature, The Way Post

Remington’s artwork was in popular demand even during his lifetime, selling for high prices. With so much value attributed to a work by Remington, many have attempted to forge the artist’s signature or “enhance” a painting in order to increase the artwork’s market value. Remington scholar Peter Hassrick once speculated that there may be more Remington forgeries than of any other American painter. Whether altered by his own hands or at that of another, Remington’s artwork can sometimes leave us with more questions than answers.

[…] As mentioned in a previous blog post, the similarities between The Way Post and the work of one of Remington’s contemporaries, William de la Montagne Cary, is striking. Like Remington, Cary was also a Western illustrator around the same time period (1840-1922). Compare The Way Post with Cary’s The Strong Cup from the Gilcrease Museum’s collection, which is similar in subject, media and size. […]