Charles M. Russell | First Wagon Trail (First Wagon Tracks) | 1908 | Pencil, watercolor and gouache on paper | 18 1/4 x 27 inches

The scene from Russell’s exquisite watercolor from 1908, First Wagon Trail, would have been set in the 1840s, when wagon trains heading to west first cut paths across the plains. These warriors show little evidence of contact with whites. The wagon tracks have these men wondering what kind of sizable beast has left the tracks.

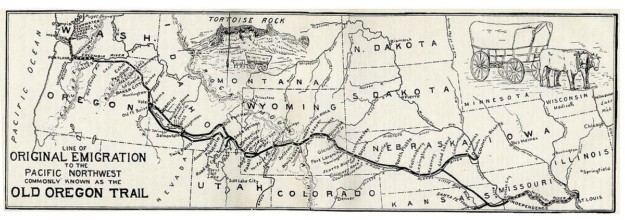

Originally, between about 1811 and 1840, one could only traverse the trails across the plains by foot or horseback. In 1836, the first wagon train was organized from Independence, Missouri, clearing a trail all the way to Fort Hall, Idaho. Eventually, wagon trains pushed farther west, creating what we now know as the Oregon Trail.

“Oregontrail 1907”. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Oregontrail_1907.jpg#/media/File:Oregontrail_1907.jpg

When the pioneers and explorers first reached the plains, they noticed how the country had changed. Accustomed to their forests and prairies, the travelers described the landscape as “desert.” The air became more dry, the landscape more barren – no trees, no water. The Great Plains, unattractive to settlers, remained illegal for homesteading until after 1846.

The year 1852 marked a turning point, as more people than ever before were traveling west. Those going to California alone increased from 1,100 in 1851 to 50,000 in 1852. Contributing to some of the upsurge in the westward emigration population was the rise in the number of women accompanying the wagon trains, from whom we have several written accounts of their experience. “Tonight we pitch our camp for the first time. Our campground is a beautiful little prairie, covered with grass and we feel quite at home and very independent,” wrote 17-year-old Eliza Ann McAuley in her diary on April 12, 1852 as she traveled from Iowa to California.

Today, highways like Interstate 80 roughly trace parts of the historic Oregon Trail and pass through towns across Wyoming and Nebraska that were first established to serve travelers using the old trail.

Leave A Comment