*The following is researched and written by Dr. Mark Thistlethwaite, retired Kay and Velma Kimbell Chair of Art History TCU School of Art*

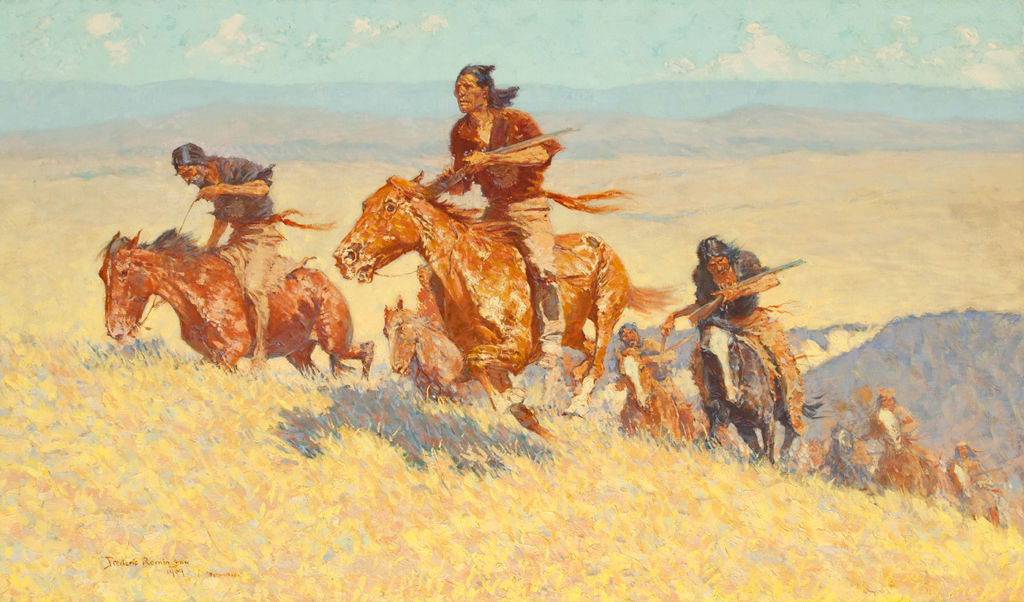

Seeing a work of art “in a different light,” as the apt title of the Sid Richardson Museum’s Winslow Homer-Frederic Remington exhibition suggests, really can change the way we perceive it. This was brought home to me when I came upon the museum’s great painting The Buffalo Runners–Big Horn Basin (1909) in the Amon Carter Museum of American Art’s recent exhibition Mythmakers: The Art of Winslow Homer and Frederic Remington. This dynamic Remington composition was installed adjacent to Homer’s intriguing Watching the Breakers (1891; Gilcrease Museum).

Winslow Homer | Watching the Breakers | 1891 | Oil on canvas | Gift of the Thomas Gilcrease Foundation, 1955 Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma | Accession No. 0126.2264

The two paintings appear so unalike: in one, two imperturbable women are solidly planted on the rocky coastline as waves crash about them under a steely, threatening sky; in the other work, a charging, forceful group of Métis race across a vast sunlit landscape. Yet despite their dissimilarity, what struck me when viewing The Buffalo Runners–Big Horn Basin in this new context was how it did relate to the Homer seascape in terms of expressing the longstanding tradition of allegorically linking western lands to the ocean.

In a 1541 letter to the Spanish king, the conquistador and explorer Francisco Vázquez de Coronado y Luján noted: “I reached some plains, with no more landmarks than as if we had been swallowed up in the sea.” Three hundred years later, Santa Fe trader Josiah Gregg, in his book Commerce of the Prairies (1844), echoed Coronado’s observation when he described the western land as “the grand ‘prairie ocean’; for not a single landmark is to be seen for more than forty miles.”[1] This land-ocean metaphor resonated with Americans throughout the nineteenth century and beyond.

James Fenimore Cooper’s popular 1827 novel The Prairie helped embed the trope in people’s minds by a passage such as this:

From the summits of the swells, the eye became fatigued with the sameness and chilling dreariness of the landscape. The earth was not unlike the ocean, when its restless waters are heaving heavily . . . There is the same waving and regular surface, the same absence of foreign objects, and the same boundless extent to view.[2]

Quite a stirring use of the metaphor, especially considering that Cooper had not traveled to the West and was penning his novel in Paris. He was, however, drawing upon a published record of Major S. H. Long’s western expedition of 1819-20.

An author who did go west early on was Washington Irving. Included in the account of his 1832 experiences, Irving offers a variation on the land-ocean metaphor that resonates wonderfully with Remington’s later The Buffalo Runners–Big Horn Basin when he writes: “An Indian hunter on a prairie is like a cruiser on the ocean.”[3] While Irving’s volume is not listed among Remington’s library holdings, other books the artist owned contain phrases such as “The waving surface [of the prairie] soon became regular, like the swell of the ocean,” “We overlooked the grand ocean of the Plains,” and “an ocean of gray chapparal.”[4]

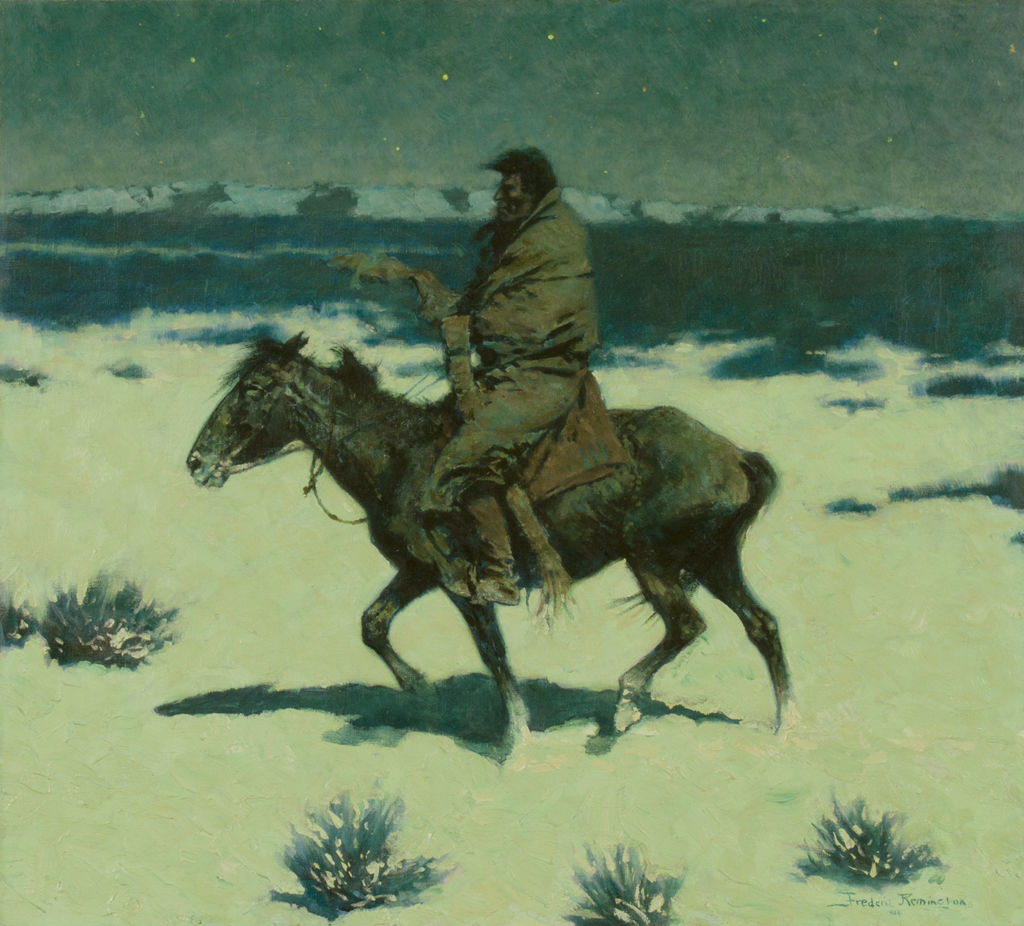

Approaching the Sid Richardson’s In a Different Light: Winslow Homer & Frederic Remington exhibition with the land-ocean figure of speech in mind, I was struck by how well the installation of Remington’s The Dry Camp (1907) next to Homer’s Two Figures by the Sea (1882) visualized the metaphor. Like the women in Homer’s composition, Remington’s lone figure (in front of what seems to be a crumpled “prairie schooner”) takes a tentative stance in a harsh, intimidating, and seemingly interminable space–an ocean of parched prairie or desert.[5] Much the same could be said of The Luckless Hunter (1909) by Remington, which hangs on the wall opposite Two Figures by the Sea.

Winslow Homer (1836-1910) | Two Figures by the Sea | 1882 | Oil on canvas | Denver Art Museum | 1935.8

If the prairie was regarded metaphorically as an ocean, you might wonder if the sea was conceived as a prairie. Yes, it was, but not as often. One striking instance and extensive employment of the metaphor is Herman Melville’s novel Moby-Dick, or The Whale (1851), in which the ocean is described several times as like a prairie. Such a shift in perspective, like viewing an artwork in a new context, could lead perhaps to seeing not only Remington’s works, but also Winslow Homer’s Two Figures by the Sea (1882) in a very different light indeed.

We invite you to explore this theme further as you journey through the exhibit with our 360-degree virtual tour feature.

[1] This quotation and the preceding one are found in Robert Thacker, The Great Prairie Fact and Literary Imagination (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1989), 44, 14.

[2] James Fenimore Cooper, The Prairie, A Tale (London: Henry Colburn, 1827), 1: 14.

[3] Washington Irving, A Tour of the Prairies (New York: John W. Lovell, 1883), 16. First published in 1835.

[4] Frederick Law Olmstead, A Journey through Texas (New York, Mason Brothers, 1859), 98; Samuel Bowles, Our New West (Hartford, Connecticut: Hartford Publishing Company, 1869), 173; Richard Harding Davis, The West from a Car Window (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1892), 42.

[5] “The yellow ocean of sand” is a description of the American desert in John Van Dyck, The Desert (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1904], 214. First published in 1901.

Leave A Comment