Last week we had the good fortune to be joined by Karen Barber, Curatorial Fellow in Photography at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, where she is currently working on a project related to photography and Native America. Karen talked to us about the continuing legacy of George Catlin’s Indian Gallery in 19th and 20th-century photography.

After amassing an Indian Gallery of more than 500 paintings, Catlin began to exhibit his collection to American audiences. He believed that Indian cultures were vanishing and would be known by future generations only through the visual record he was preserving. What he didn’t know at the time was that others would continue his mission through a new visual record: photography.

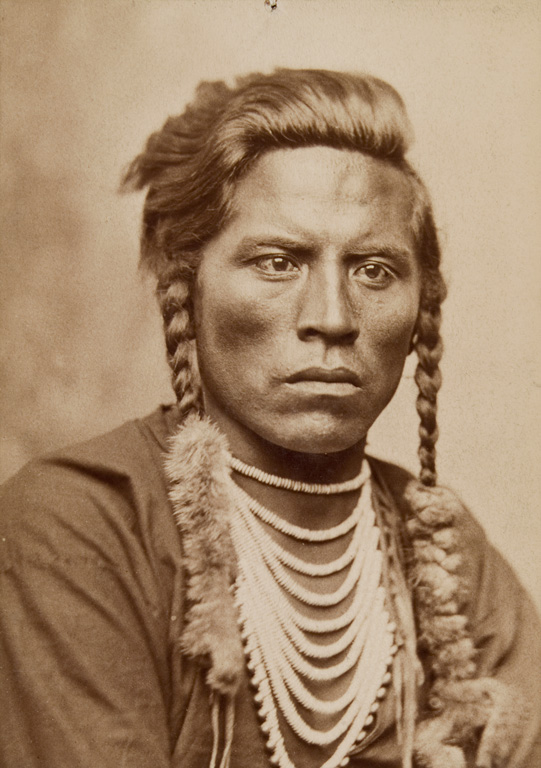

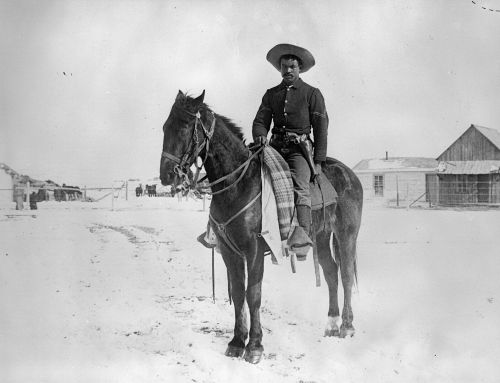

David Barry, Curley, ca. 1885-1895, Albumen silver print, Courtesy of Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

David F. Barry, Sitting Bull or Tata’nka I’Yota’nka, ca. 1886, Collodion silver chloride print, Courtesy of Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas

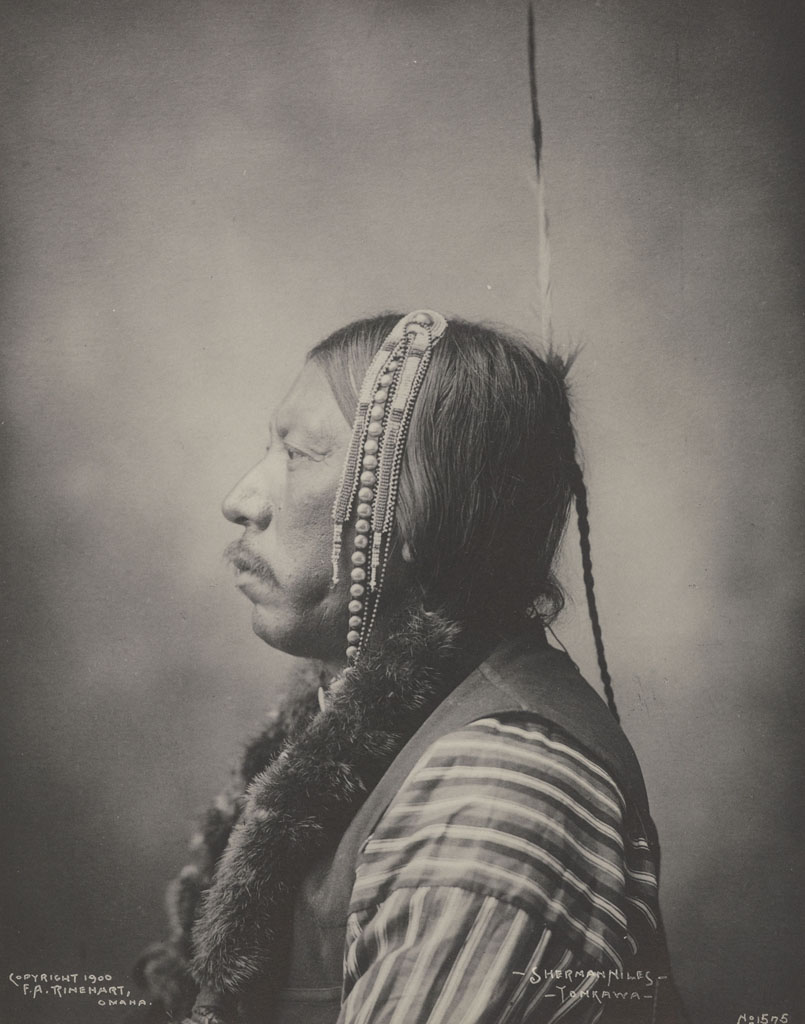

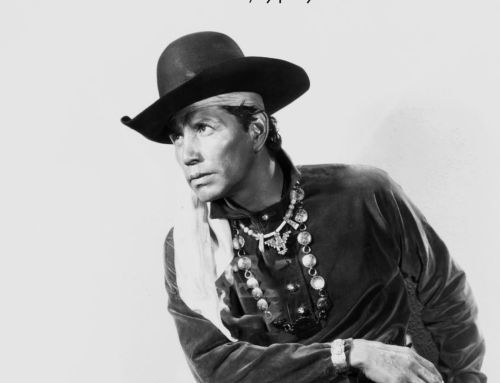

Frank A. Rinehart, Portrait of Sherman Niles in Partial Native Dress with Ornaments, 1900, Platinum print, Courtesy of Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

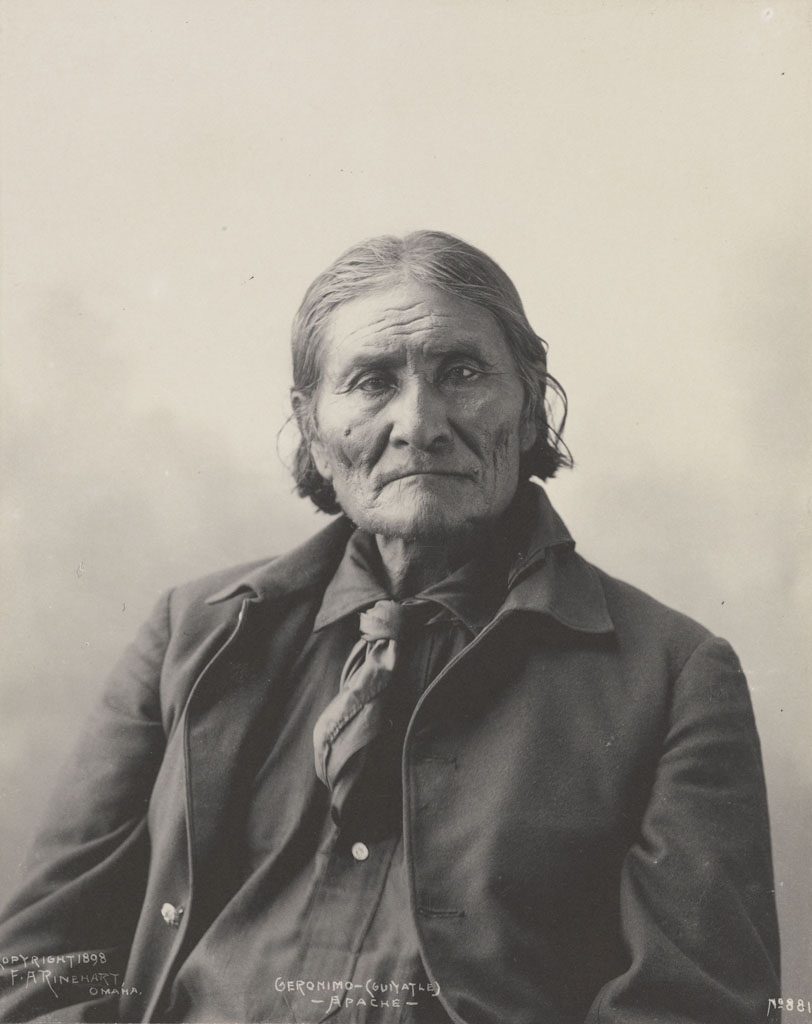

Frank A. Rinehart, Geronimo, (Guyatle), Apache, ca. 1898, Platinum print, Courtesy of Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas;

The same year Catlin left the U.S. to find new prospects abroad in Europe in 1839, the birth of photography was publically announced. Six years later, David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson produced what some consider to be the first existing photograph of a Native American. Photography was quickly adopted as the favored medium by which to record American Indians. In addition to its speed, the reproductive aspect of photography appealed to many. The insured survival of an image had become a newly cherished feature, particularly after the devastating 1865 fire at the Smithsonian Institution, which destroyed their entire collection of invaluable Indian portraits by artists Charles Bird King and John Mix Stanley. By the late 19th century, photographers like Edward Curtis and Joseph Kossuth Dixon were commissioned to lead expeditions with a mission similar to Catlin’s – to study the habits, costumes, and villages of Native Americans.

Edward S. Curtis, The Old Cheyenne, 1930, Photogravure, Courtesy of Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas

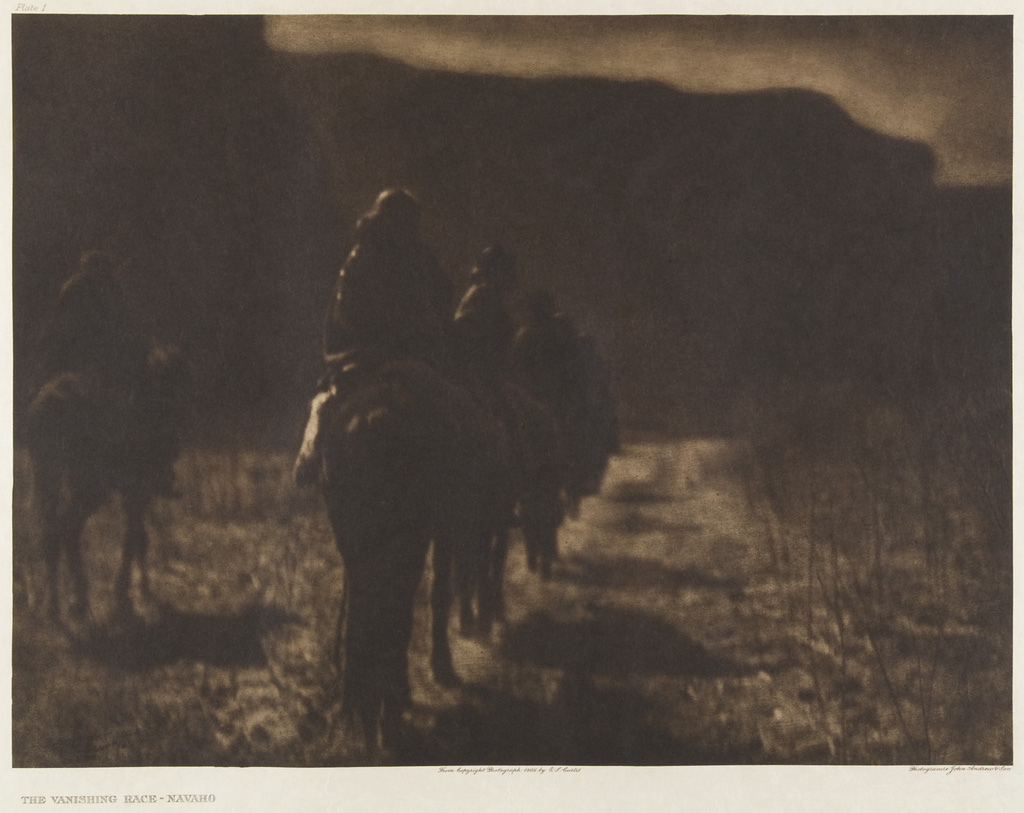

Edward S. Curtis, The Vanishing Race-Navaho, 1907, Photogravure, Courtesy of Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas

Both Curtis and Dixon have been criticized for the sentimental quality of their work. Although photography began as a simple record of reality, by the turn of the 20th century, pictorialism dominated the field. Through staged shots and photographic manipulations, photographers transformed what was once a purely documentary medium into an art form. By “creating” their own image, Curtis and Dixon’s photographs reinforced the romanticized identity of the “noble savage.” Like Remington and Russell’s paintings that helped craft the myth of the Wild West, photographers began to use their camera to construct a notion of the Indian.

Today, many American Indians have stepped behind the lens to respond to the romanticized representation of Native peoples. Photographers like Tom Jones (Ho-Chunk), Will Wilson (Diné), and Rosalie Favell (Cree Métis) examine the experiences of the American Indian and seek to portray the complex identity of their cultures. The result is a contemporary vision of Native North America.

Leave A Comment