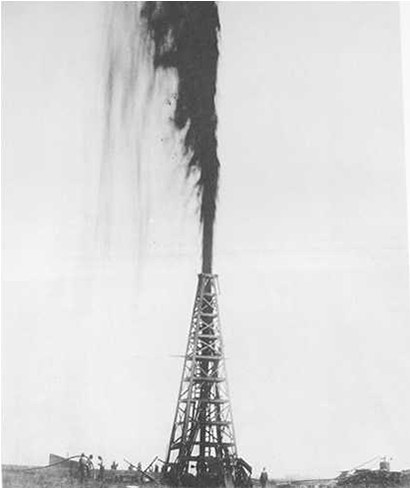

On January 10, 1901, Spindletop, the famous oil field in Beaumont, Texas, “gushered” in an era of transformation for the state of Texas. The development of oil in Texas helped transform its once rural economy to one spearheaded by the petroleum industry and, likewise, steered its population from rural to urban. In 1900, only 17% of Texans lived in urban centers while 83% of the state’s population was rural. Flash forward to a little over a hundred years later in 2010, when we see those numbers flipped – 83% urban vs. 17% rural.

Although Spindletop was a pivotal moment in Texas history, it was not the first discovery of oil in the Lone Star State. Historians recount how American Indians in Texas first told European explorers about oil, believing the substance to have medicinal uses. In July 1543, Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto’s expedition, led by Luis de Moscoso Alvarado, found themselves on the Texas coast between Sabine Pass and High Island. Moscoso reported that the group found oil floating on the surface of the water and used it to caulk their boats. Later, Lyne T. Barret drilled Texas’ first producing oil well in 1866 at Melrose in Nacogdoches County. Other wells followed, making Nacogdoches County the site of Texas’ first commercial oil field, first pipeline and first effort to refine crude.[i]

Despite not being the first oil well, Spindletop set off the oil boom in Texas, resulting in an influx of wildcatters. A wildcatter is someone who drills wells in areas not known to be oil fields. Wildcatters were essentially gamblers, taking a lot of risk in hopes to strike it big. Sid Richardson was an early – and eventually very lucky – wildcatter.

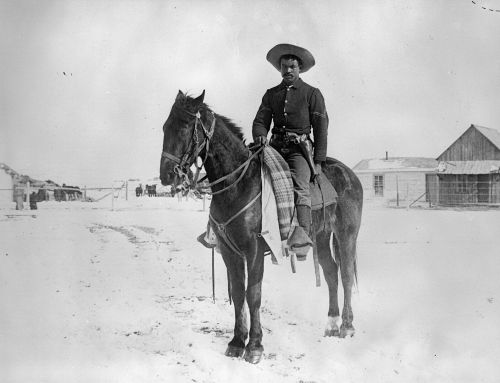

Sid Richardson learned the oil business from the ground up, beginning his boom-and-bust career in 1911 hauling pipe and working on an oil well platform near Wichita Falls, Texas, followed by short stints as an oil scout in Louisiana and Texas. As an independent trader in leases, and independent oil promoter and operator, he won and lost two sizeable fortunes in setbacks in 1921 and 1930.

Keystone Field, Derricks and Sand Dunes | Esther Bubley | B/W photograph | November 1945

When oil prices improved in 1933, Sid began wildcatting in West Texas. With $40 borrowed from his sister Annie, he began a “poorboy” operation—buying some materials on credit, borrowing others, wrangling leases, and arranging with workers to take small pay in cash and more in oil. H.A. “Red” Coulter, a driller who worked for Sid, reminisced about those early days in the Winkler County News in Kermit, Texas, “During the Depression, Sid brought the country out with nothing but nerve. Times were hard . . . the price of oil was so low, Sid had trouble getting enough money to meet his payroll . . . . and Christmas of 1933 was approaching . . . . Our grocer in Wink had cut off our supply. We appealed to Sid and he said that he had credit in Fort Worth and would send out a truckload of groceries . . . . It was the biggest Christmas any of us had ever experienced . . . even though none of us could even buy a postage stamp.”

After drilling two dry holes in Winkler County, Richardson struck oil on the third attempt. With the income, he invested in leases in the Keystone field of Winkler County and the Estes of Ward County. By 1935, Sid and his nephew, Perry R. Bass had become partners. Their big strike—one of the biggest in West Texas—came a few years later. Of the 385 wells they drilled, only 17 were dry. By the end of 1940, Richardson had 33 producing wells in the Keystone field, 7 in the Slaughter field, 38 in the South Ward field, and 47 in the Scarborough field.

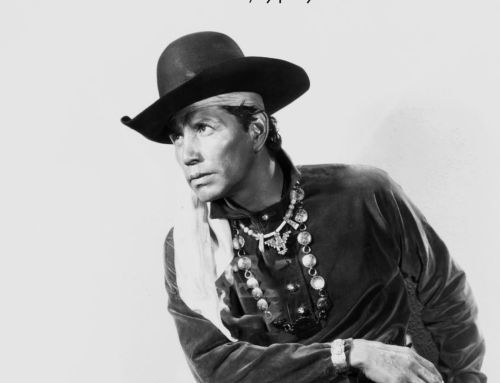

Peter Hurd, Portrait of Sid Richardson, 1958, Oil on panel, 32 x 48 inches

Years later, reflecting on his success, Sid downplayed it all with his characteristic humor and modesty, “Luck helped me, too, every day of my life. And I’d rather be lucky than smart, ‘cause a lot of smart people ain’t eating’ regular.”

[i] Mary G. Ramos, editor emerita, for the Texas Almanac 2000–2001, https://texasalmanac.com/topics/business/oil-and-texas-cultural-history

As luck would have it, success found you.