The impact of Charles Russell’s friendship with pioneer dude rancher Howard Eaton appears twice in our current exhibit, Charles M. Russell: Storyteller Across Media. The first occurrence is in Russell’s 1916 oil painting Man’s Weapons Are Useless When Nature Goes Armed. In the bottom left corner viewers will see an inscription to Eaton from his friend CMR.

Charles M. Russell | Man’s Weapons Are Useless When Nature Goes Armed (Weapons of the Weak; Two of a Kind Win) | 1916 | Oil on canvas | 30 x 48.125 inches

Detail of Man’s Weapons showing Russell’s signature and inscription to Howard Eaton

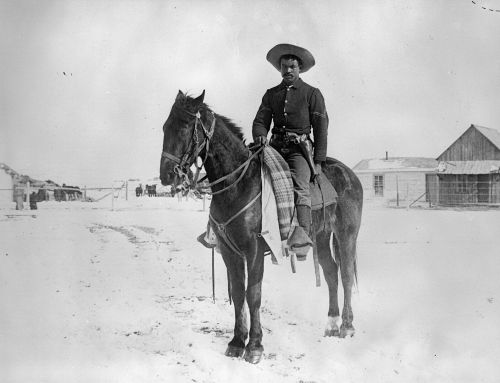

Who was Howard Eaton? Originally from Pittsburgh, Eaton had moved to North Dakota in 1882 before settling permanently near the Big Horn Mountains in Wyoming. This is where his dude ranching business grew in popularity.

What is a dude ranch? Think of it like the original Western vacation. A “dude” in the late 19th century was what ranchers and cowboys called city slickers. As urban centers grew, people living on the East Coast and Midwest longed to escape the crowds and noise of city life. Dude ranches offered nourishment and a rejuvenation of spirit.

Howard Eaton was one of the first dude ranchers, and his Eaton dude ranch is still open to visitors today on Wolf Creek, operated by fourth and fifth generation Eatons. The ranch sits near some national historic sites and parks. In the early 20th century, Howard Eaton expanded his operation to include trail rides through the newly established Glacier National Park.

In 1915, Charlie Russell accompanied Eaton on a trail ride through Glacier, which included a stop at Bull Head Lodge, Russell’s summer cabin. Eaton hired his cowboy artist friend on the 300-mile trek with the understanding that Russell would entertain the “dudes” with his stories of the American West.

Russell (third from left) modeling for (from left) Howard Eaton, artist Joe Scheuerle, and an unidentified man in Glacier in 1915, AJ Baker, photographer, MHS photograph archives, Helena, Pac 99-52.MI, Courtesy of Montana’s Charlie Russell: Art in the Collection of the Montana Historical Society

The following year, on September 9, Charlie and Nancy embarked on a six-week trip to see the Grand Canyon, visiting Diné and Hopi country. The trip included Canyon de Chelly, visits to three pueblos, and a trail ride into the Grand Canyon. They kept a photo album of the trip, which shows Charlie relaxed and happy. The couple were both completely enchanted by Arizona. Nancy later recounted to a friend, “This trip has been a trip of memories. Chas. just loved it all and had such a good time every day then around the camp fires at night they always had the big talk.”

The Eaton party on Bright Angel Trail, Howard Eaton in the lead in vest and tie, Photograph by Almeron J. Baker, Helen E. and Homer E. Britzman Collection. TU2009.39.7650.81/D.10.845. Gilcrease Museum Archives. University of Tulsa.

Nancy and Charlie Russell at chow time, Photograph by Almeron J. Baker, Helen E. and Homer E. Britzman Collection. TU2009.39.7650.20/D.10.784. Gilcrease Museum Archives. University of Tulsa.

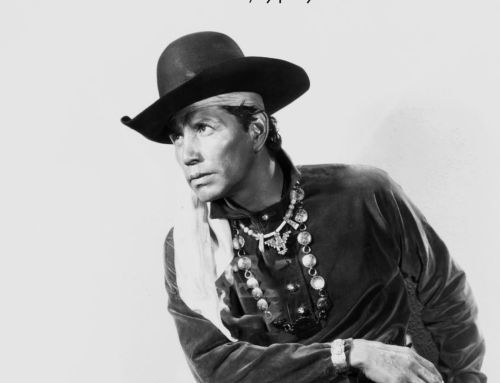

It was a transformative experience for Russell. A few years after the Arizona trip, Russell wrote to his artist friend Ed Borein about the impression that trip had on him, particularly his observations of the Navajo people.

“I am glad I went and I whish I knew those people and there past…If I savyed the south west like you Id shure paint Navys [Navajos]…these riders looked lik the real thing in there high forked saddles and concho belts silver ore turquis necklaces and year rings [earrings] they were all hatless som wore split pants…they rode short sturrips an each packed a skin rope. They were not like the Indians I know…in a mixture of dust and red sunlight it made a picture that will not let me forget Arizona.”[1]

The young artist Joe De Yong, who was house sitting for the Russells while they were traveling, reported that Charles and Nancy had returned from Arizona with many souvenirs from Navajo country, including blankets and silver work.[2] Listed among the materials found in Russell’s Great Falls studio that were obtained during this 1916 trip include:

· Navajo concho belt of silver with turquoise set buckle

· Navajo woven wool, half of a woman’s dress

· two small Navajo looms with unfinished weavings (predominantly red wool)

· Navajo moccasins of rough leather with latigo soles

· Navajo wooden rabbit stick or throwing stick with rawhide hondo on one end

· Navajo saddle blanket, banded red, black, white (Russell used it with his saddle)

· Navajo flat braided leather rope

· Navajo typical saddle with looped cantle and pommel, leather covered tree, brass tack decoration

Known to much of the world as Navajo, members of the tribe refer to themselves as the Diné, meaning “(the) people.” Today, the Navajo Nation is the largest federally recognized tribe in the U.S. as well having the largest reservation in the country, which stretches across Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah.

In his letter Russell had noted the silver concho belts of the Navajo riders. Silversmithing was and remains an important art form for the Navajo people. Russell also remarked on the jewelry and the turquoise, which Navajo artists had started incorporating into their silver designs in the late 19th century.

Charles M. Russell, Navajo Trackers, 1926, Watercolor on Paper, Private Collection

Thanks to Howard Eaton and his trail rides, depictions of Diné people became part of Russell’s artistic repertoire. Russell repeatedly painted Navajos in watercolor over the next couple of years, and then again during the last year of his life in the 1926 Navajo Trackers, which is on display in our current exhibit, Charles M. Russell: Storyteller Across Media. A group of Navajo riders are traveling through a landscape full of the sagebrush, flowering yuccas, and twisted Joshua trees of Arizona’s Painted Desert. The painting exemplifies Russell’s watercolor prowess endemic of his later years with its use of varied washes and mottled brushwork. The shimmering colors are applied using both deliberate and accidental effects such as the strokes used to define the foreground foliage and the pools, puddles, and even drips that create the contrasting shadows. This is the display of a master watercolorist.

[1] Charles Russell to Edward Borein, February 13, 1918, The M.C. Naftzger Collection, Wichita Art Museum

[2] Joe De Yong to Adrian and Mary De Yong, February 17, 1917, Joe De Yong Papers, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum

Leave A Comment