Three of the often cited reasons for the closing of the frontier of the American West typically include the telegraph, the transcontinental railroad, and barbed wire.

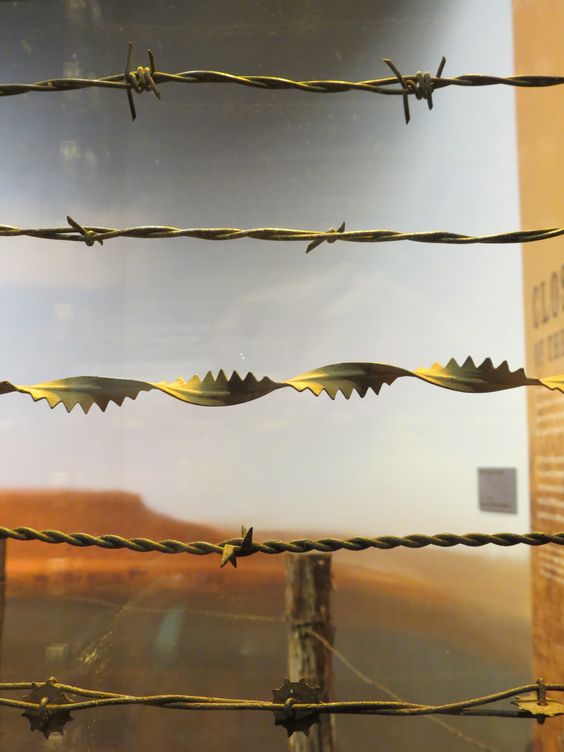

Display of different types of barbed wire. Cattle Raisers Museum. Fort Worth, TX.

So you may be surprised to learn that large scale manufacturing of barbed wire began first in the Mid-West in central Illinois (1874-75) before expanding to the American West.

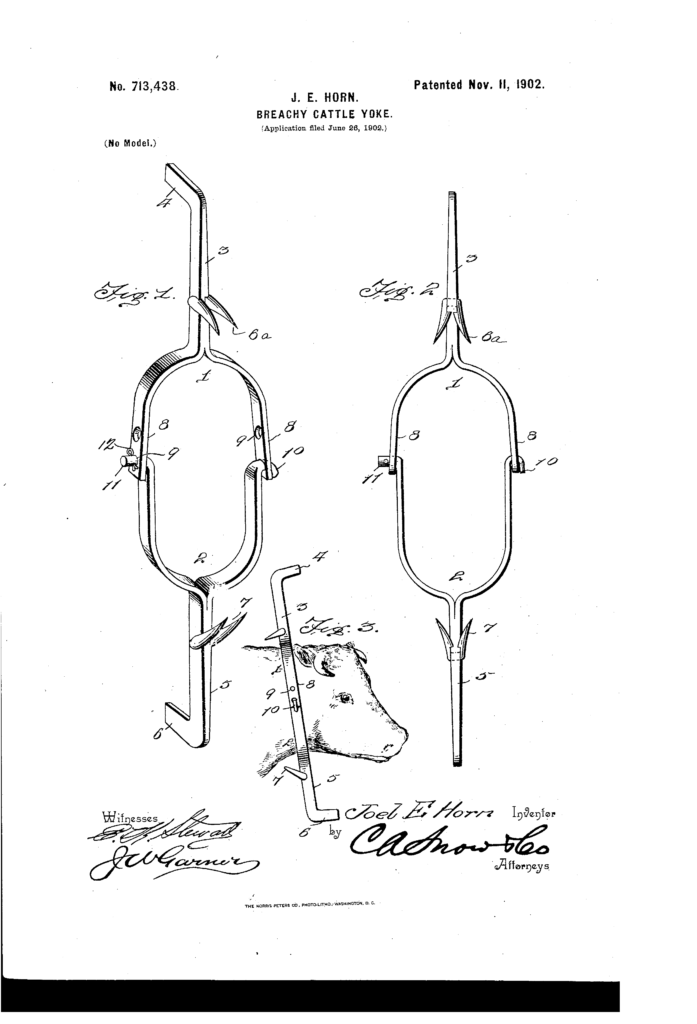

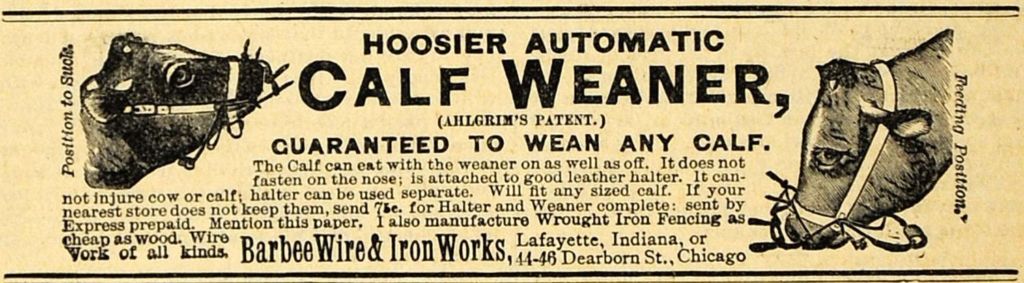

The invention of barbs also made its way into other preventative products, such as calf weaners, cattle yokes & pokes, and even into poison bottle designs.

Joel Horn Breachy Cattle Yoke

1890 Ad Hoosier Automatic Calf Weaner

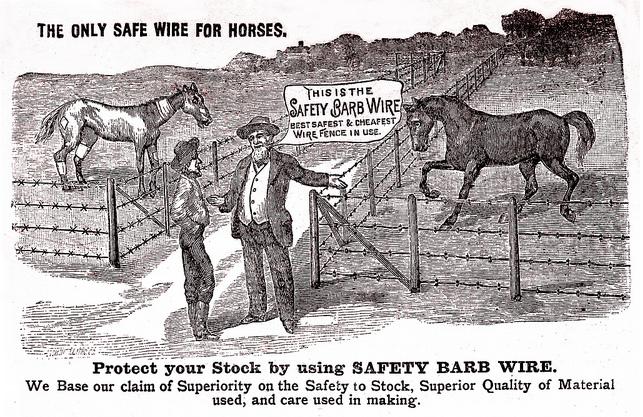

Barbed wire was invented mostly for cattle, but was also a means to deter other animals and humans from crossing over or through the fencing. It was certainly effective. However, accounts of the harmful effects of barbed wire on livestock resulted in an outcry from not only agriculturalists and stockmen but the public at large, including local chapters of the early formation of the Humane Society. Stories spreading the cruel and inhumane nature of barbed wire fences circulated in the press. Some such stories included rather graphic accounts of cows & their calves or horses & their colts running into barbed fences.

Safety Barb Wire Advertisement Circa 1895

Cochliomyia hominivorax or screwworm fly

As production of barbed wire grew, so too did its opponents, who called for legislative action. States like Connecticut, Vermont, New Hampshire, Colorado, and Texas proposed bills to restrict or outlaw use of barbed wire. Court hearings recorded testimony of those for and against. Some farmers and their advocates claimed barbed fencing was “one of the greatest inventions of the age.” Many opponents of these anti-barbed wire bills argued that barbed wire fencing saved more animals than it hurt and would do “nothing more than scratch any stock.” However, there was growing evidence to the contrary in the Great Plains. In Texas, harmless scratches developed into nesting grounds for the screwworm fly, which embedded its eggs into the animal’s flesh, eating its tissue and sometimes resulting in death. The parasitic fly was native to the tropical Americas and appeared in the southwest US in the 1840s, eventually growing into an epidemic problem in the 20th century. Large herd loss was also a result of a combination of barbed wire fencing with severe storms & blizzards of the 1880s, as cattle trampled those trapped in the fencing during a drift or stampede.

In addition to court hearing accounts and other published stories, evidence of the rise in injuries as a result of animal and human contact with barbed wire fencing is seen in the upsurge of medicines designed specifically for barbed wire injuries, such as Silver Pine Healing Oil.

“Silver Pine Healing Oil, International Stock Food Company, Minneapolis, Minnesota,” DPLA Omeka, accessed November 10, 2017, https://dp.la/exhibitions/items/show/811815.

Despite these concerns, there was a drastic increase in the amount of barbed wire made, with 120 million pounds sold in 1881 and an estimated 250,000 miles of barbed wire fences across the country within the same year. Today there are over 115,000 miles of old, unused barbed wire fencing that kills over 92,500 animals annually due to collisions. Unfortunately, it is expensive and time consuming to track all of this fencing. However, technologies such as geographic information system (GIS) are helping. Just as researchers in Canada are using GIS to track black bears & wolves to determine where they intersect with roads, efforts to map all the old barbed wire fencing in the American West are being pursued. The good news is that in addition to regulations making new barbed wire fencing less harmful, where they are cutting down outdated and idle barbed fencing is helping to reduce the percentage of animal deaths.

Of course, there’s much more to the fascinating story of barbed wire. I recommend checking out the newly published book from Texas A&M Press, The Perfect Fence: Untangling the Meanings of Barbed Wire by Lyn Ellen Bennett and Scott Abbott.

Leslie,

Thank you for your recent blog entry regarding our book The Perfect Fence: Untangling the Meanings of Barbed Wire. Interested parties might also check out the below websites which provide more information about the book and its contents:

https://doublevisionbooks.wixsite.com/the-perfect-fence

http://www.tamupress.com/Catalog/ProductSearch.aspxsf=ss=Connecting%20the%20Greater%20West%20Series

And anyone interested in reading about how barbs appeared in association with other kinds of technology, Lyn recently gave a paper at the 2017 Western History Association annual meeting covering this very topic entitled “The Expansion of Barbed Technology at the End of the 19th and Early 20th centuries.” Feel free to contact her at lbennett@uvu.edu.

Bests,

Scott Abbott and Lyn Bennett

Thank you for sharing the additional resources, Scott. I had the great fortune of attending the talk at the WHA 2017 conference, and was enthralled with all three presentations. The history of barbed wire and its meanings is so fascinating!