While Charles Russell led a successful artistic career, largely in part to the business savvy of his wife and manager Nancy Cooper Russell, not every creative output was intended for sale. His illustrated letters and even some significant paintings and sculptures were made specifically as gifts for the artist’s close friends. Some of these works were gifted to reciprocate the hospitality Charlie and Nancy received during their travels to promote his art. Who were these friends? A section of artworks featured in our current exhibit, Charles M. Russell: Storyteller Across Media, relate to the friendships Russell kept. The cowboy artist cherished his relationships with fellow Montanans and others, including cowboys, artists, collectors, politicians and — late in his life — movie stars like western actors Will Rogers and William S. Hart. Among his more famous artist friends were California-based artist Maynard Dixon and New York-based illustrator Philip Goodwin.

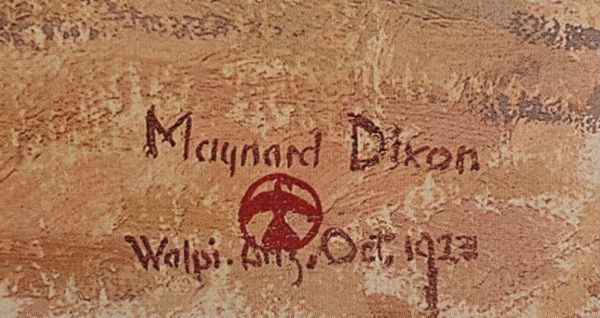

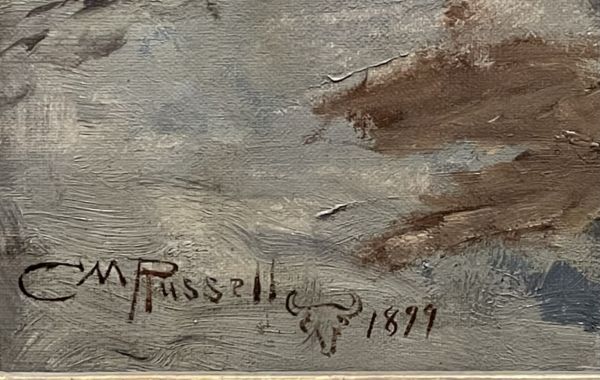

Maynard Dixon and Russell first met each other sometime after 1908 in New York City, likely in the studio of Edward Borein, a mutual friend and artist. The East Coast location of the encounter is ironic considering that these men were two premier artists of their own kind of American West: Dixon based in California while focusing on subjects of the Southwest and Russell based in Montana focusing on subjects of the northern Plains. In addition to depicting the West, both artists included monograms in their signatures: Russell a buffalo skull; Dixon a thunderbird. But while Russell was concerned about historical accuracy in his work, Dixon was more interested in interpretation. “The melodramatic Wild West is not for me the big possibility. The nobler and more lasting qualities are in the quiet and most broadly human aspects of western life. I am to interpret, for the most part, the poetry and pathos of the life of western people, seen amid the grandeur, sternness and loneliness of their country.”[1]

Detail of monogramed signature of Maynard Dixon

Detail of monogramed signature of Charles Russell

Like Russell, Dixon was largely self-taught. Although Dixon had enrolled at the California School of Design in San Francisco, his studies were short lived – only three months. Shortly afterwards, like Russell, he became an illustrator, and like Russell, developed a following.[2]

After the devastating earthquake of 1906, Dixon was unable to find work in San Francisco nor nearby Los Angeles, and eventually relocated to New York City, where he eventually encountered our friend Russell, connecting over their shared interest in the American West. Russell was ten years Dixon’s senior. Dixon returned to San Francisco in 1912. The two artists kept in touch and followed each other’s careers. After seeing images of Dixon’s 1912 mural for Anita Baldwin, Russell responded: “Think your pictures were fine they looked mighty real to me your Indians ponees and ldges [lodges] were all might shookum I am glad of your success and hope you keep pulling of good things till your light goes out and hope it burnes long and bright with out a flicker.”[3]

Dixon visited Russell at the cowboy artist’s Bull Head Lodge in Glacier National Park during the summer of 1917. The stay was brief. For someone who was used to expansive views of the sky and the distant horizon, Dixon felt stifled by the denseness of the surrounding views. “I did not think too much of the mountains.”[4] Despite his challenges painting the local landscape, Dixon enjoyed Russell’s company while at Bull Head Lodge.

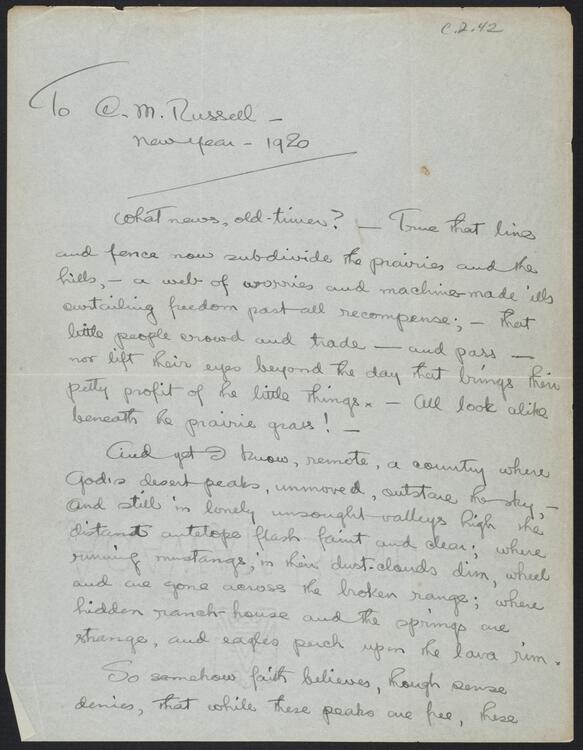

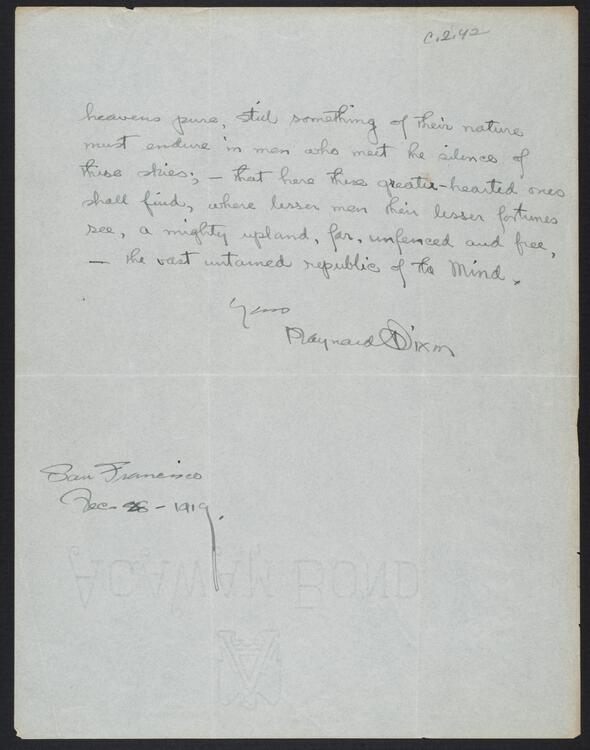

Though the two did not reunite for another 7 years, they stayed in touch. In 1920, Dixon sent Russell a poem titled “To an Old Timer” in which Dixon shares Russell’s distaste for the growing development and industrialization of the American West.

From Maynard Dixon to Charles M. Russell, 1920, ink on paper, Charles M. Russell Research Collection, Gilcrease Museum, The University of Tulsa, TU2009.39.588.1-4

What news, old timer? True that line and fence

now subdivide he prairies and the hills, —

a web of worried and machine-made ills

impeded your freedom without recompense;

that little people crowd and trade, and pass –

nor lift their eyes beyond the day that brings

their petty profit of the little things –

where once the west wind turned the prairie grass.

And yet I know, remote, a country where

God’s desert peaks, unmoved, outstare the sun:

and still in lonely unsought valleys run

the distant antelope; and flashing clear

stampeding mustangs from their dust-clouds dim

wheel and are gone across the broken range;

the hidden ranch house and the springs are strange;

and eagles perch upon the lava rim.

So somewhere faith believes, though sense denies,

that while these peaks are free, these heavens pure,

still something of their nature must endure

in men who meet the silence of these skies;

that here these greater-hearted ones shall find,

where lesser men their lesser fortunes seek,

a mighty upland, clear from peak to peak –

the free unfenced republic of the mind.[5]

Another young artist Russell befriended was Philip Goodwin who was eighteen years Russell’s junior. Born and raised in New England, Goodwin met Russell when the cowboy artist was visiting New York City in 1904 or 1905. Charlie and Nancy were in the city to meet with publishers and expand the market for Russell’s paintings. During this time Goodwin had a studio in the city where he was making a living as an illustrator, mostly of animal subjects. Goodwin is known today for his scenes of hunting and outdoor life, but while he was particularly close with Russell (1905-10), Goodwin was known as an animal painter. Like Russell, Goodwin painted “predicament pictures” in which man is pitted against nature or animal against animal, the outcome of such encounters remaining uncertain, and sometimes had a humorous twist.

Later, Goodwin visited Charlie and Nancy at Bull Head Lodge as well as their home in Great Falls (1907 and 1910).[6] In fact, the two artists collaborated on an art project: decorating the lodge’s cement fireplace. Goodwin incised drawings of a wolf, bear, and moose, alongside images made by Russell himself.[7] Later, the two artists sketched together in the nearby woods and lake shore. After Russell’s death, Goodwin wrote to Nancy that spending time with Russell was, “among my fondest memories…His help and influence on my life and work will always be appreciated.”[8]

Fireplace at Bull Head Lodge with etchings by Philip Goodwin and Charles Russell, 1907, photographer unknown. C.M. Russell Museum, Great Falls, Montana, Trigg Collection

Stay tuned next month for Part 2 as we continue to explore various artworks on display in our current exhibit and their connections with Russell’s friendships.

[1] Donald J. Hagerty, Desert Dreams: The Art and Life of Maynard Dixon, rev. ed. (Salt Lake City: Gibbs-Smith Publisher, 1998), 24.

[2] Thomas Brent Smith, “’Old Timer & ‘Friend Dixon’: Charles M. Russell & Maynard Dixon: Interpreters of Different American Wests,” in Charles Russell & Friends (Denver, CO: Petrie Institute of Western American Art, Denver Art Museum, 2010), 59.

[3] Charles Russell to Maynard Dixon, September 1913, in Brian W. Dippie, ed., Charles Russell, Word Painter: Letters 1887-1926 (Fort Worth, TX: Amon Carter Museum, 1993), 182.

[4] Maynard Dixon to Dane Coolidge, 1917, in Hagerty, Desert Dreams, 91.

[5] Maynard Dixon to Charles Russell, 1 January 1920, Rankin Collection.

[6] Peter Hassrick, “Goodwin & Russell: Friends Through Their Art,” in Charles Russell & Friends (Denver, CO: Petrie Institute of Western American Art, Denver Art Museum, 2010), 27.

[7] Ibid., 34.

[8] Philip Goodwin to Nancy Russell, 26, October 1926, Helen R. and Homer E. Britzman Collection, Taylor Museum, Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, Colorado Springs, CO.

Leave A Comment