Within our current exhibit, Night & Day: Frederic Remington’s Final Decade, visitors will observe how the artist returns to compositions and themes first represented in his illustrations and now reimagined as dynamically painted fine works of art. Remington’s habitual patterns of revision extend to his work in three dimensions as seen in the bronze sculptures on display in the front gallery of the museum.

Remington modeled 22 subjects for bronze casting from 1895 until his death in 1909. When he started, he used the Henry-Bonnard Bronze Co. to sand cast his first 4 bronze subjects. Then sometime in 1900, Remington began his association with Roman Bronze Works, which employed the lost-wax method of casting. In the early stages of this process, a wax replica of the artist’s model is made, during which time a sculptor may work in more detail by tooling or brushing the wax replica with hot wax. Remington enjoyed this process, and spent long hours at the foundry re-touching the wax models.

The artist’s turn from sand-casting to the lost wax process allowed Remington more control over the details and surface of each bronze. To create a lost wax bronze Remington began by developing a master model out of clay. The foundry would then make a plaster mold, and from that mold multiple hollow wax models could be made. Remington could then rework the wax models, adjusting the pliable material before the bronze cast was made. (For a more in-depth outline of the entire process, check out this silent animated video produced by the Amon Carter Museum of American Art.)

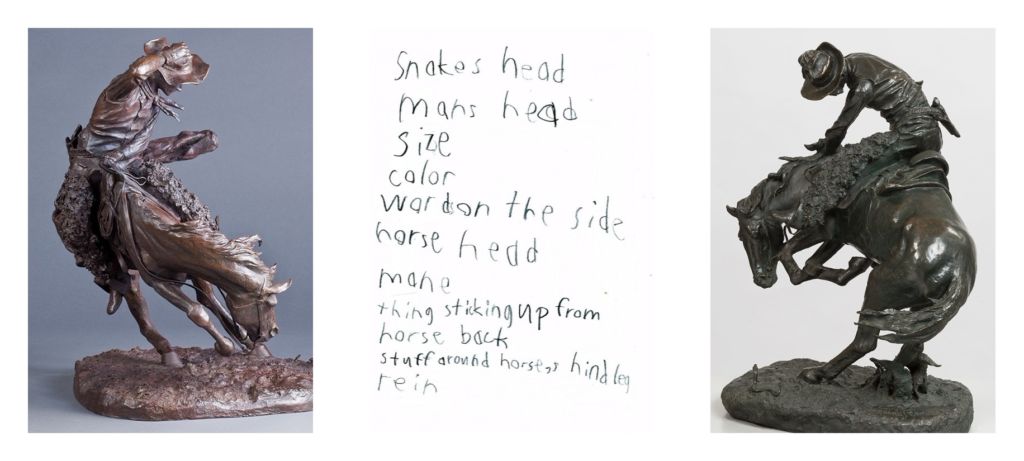

Frederic Remington | The Rattlesnake [first version] | Copyrighted January 18, 1905 | Roman Bronze Works cast #5, 1906 | Private Collection

Frederic Remington | The Rattlesnake | Copyrighted 1905 | Roman Bronze Works cast #19, 1910 | Private Collection

A young visitor’s list of noted differences between the two bronzes.

Remington’s The Broncho Buster was the first subject the artist cast in bronze. It would prove to be his most popular sculpture with 154 casts sold during the artist’ lifetime. Visitors will notice how the two casts on display of The Broncho Buster vary in detail from changes in size, the position of the rider’s hand and angle of the horse’s head, to the modification from smooth to wooly chaps. Such a complex feature and variety of changes were only possible with the lost wax process. Despite the success of The Broncho Buster, in the last two months of Remington’s life he requested his foundry, Roman Bronze Works, to enlarge the model. Unfortunately, after making his above-mentioned revisions, Remington did not live to see the final casting. After dying from complications of appendicitis, the artist’s widow Eva was left to supervise the casting of the large bronze, now seen on display at the museum.

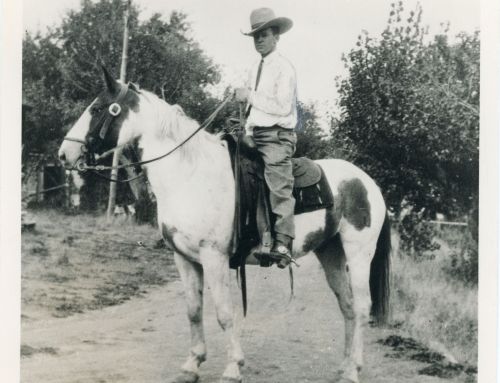

Frederic Remington, The Broncho Buster, ca.1905–1906, Bronze, Private Collection

Leave A Comment