*The following is part of a new series of blog posts researched and written by Dr. Mark Thistlethwaite, Kay and Velma Kimbell Chair of Art History TCU School of Art, and guest curator of SRM’s special exhibit Another Frontier: Frederic Remington’s East.

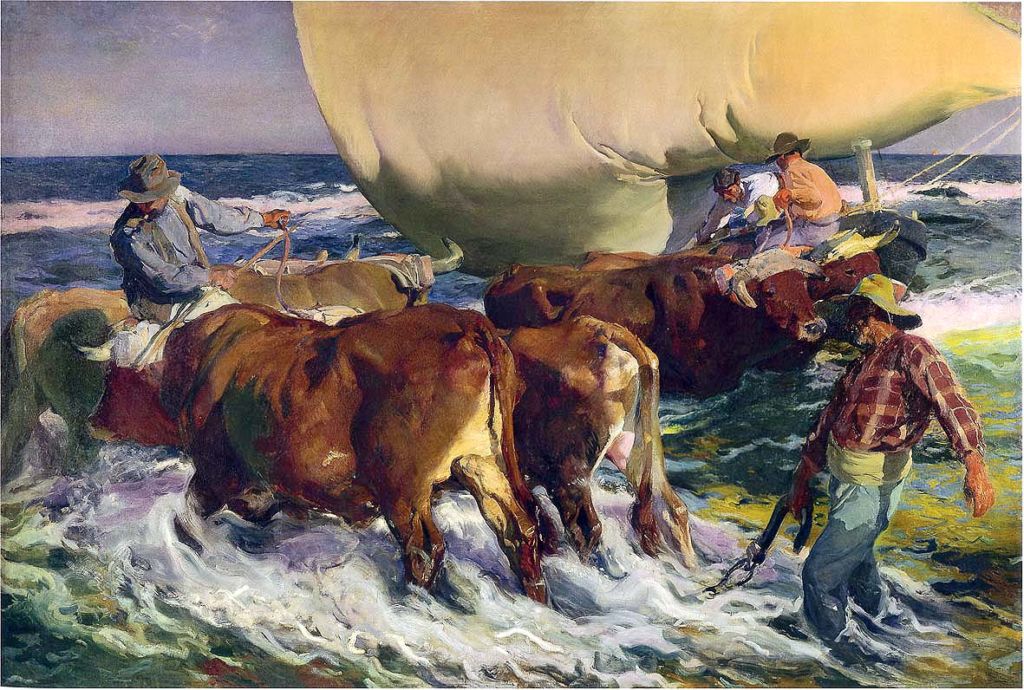

One fascinating aspect of working on the exhibition Another Frontier: Frederic Remington’s East was reading the artist’s diary entries from 1907 through 1909. Doing this helped me gain a greater sense of Frederic Remington, as person and as an artist. I was especially keen to see what artists he might mention. While I knew he was friendly with a number of American artists, including Willard Metcalf, Childe Hassam, and Charles Dana Gibson (works by the first two are included in the exhibition), I was surprised to read of his high regard for the Spanish painter Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida. After visiting a major Sorolla exhibition in New York, Remington wrote enthusiastically in his diary (February 11, 1909): “[Sorolla] makes everything else look like lead quarters. God how I wish I had money enough to buy some.” Remington was invited to a celebratory dinner in Sorolla’s honor at the Player’s Club in New York. Unfortunately, a “bad stomach and a heavy cold” prevented him from attending; “Very sorry not to meet the great man” (Diary, February 27, 1909; speaking of great men, Remington’s very next sentence reads: “Have invitation to meet [Theodore] Roosevelt at Colliers [sic] breakfast . . . “).

1. Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida, Evening Sun, 1903, Oil on canvas, 115 ¾ x 171 ¼ in., Hispanic Society of America, New York

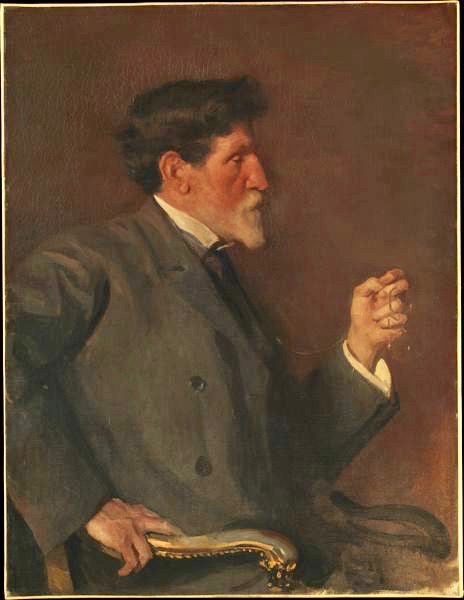

Another artist reference that I found particularly intriguing appears in Remington’s diary entry of March 10, 1908. Remington had traveled to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York to view the memorial exhibition for the American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. He considered it a “very fine show – a most wonderful portrait of him there by Miss Bay Emmett [sic] painter.” He then declares: “If she will do me, I have a crack at immortality.” This striking assertion was undoubtedly prompted by the memorial nature of the Saint-Gaudens exhibition and Remington’s obvious admiration for an artist who was unknown to me. I had come across her name in a previous Remington diary entry—“Miss Bay Emmett wants to paint my picture” (March 2, 1908)—and had not given it much thought. However having then read that he felt a portrait by her might bring him “immortality” caused me to give her my full attention.

Ellen Emmet {Rand], Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1905, Oil on canvas, 38 3/4 × 29 3/4 in., Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1908 Accession Number: 08.129

As it turns out, Ellen Emmet Rand (she married in 1911) was an accomplished and prolific portraitist. Success Magazine of 1907 included her as one of two women artists (the other being Cecilia Beaux) grouped with prominent American portrait painters, including John Singer Sargent, William Merritt Chase, John White Alexander, and Robert Henri.

Ellen Emmet (b. 1875), whose family and friends called her “Bay,” began taking art classes when she was twelve years old. As a teenager she studied at the Art Students League in New York—with William Merritt Chase, Kenyon Cox, and Robert Reid—and attended Chase’s Shinnecock summer art school. When she was about eighteen, she supported her family financially by producing illustrations for Harper’s Weekly and Vogue magazine—already she seems to have lived a life readymade for a Hollywood movie!

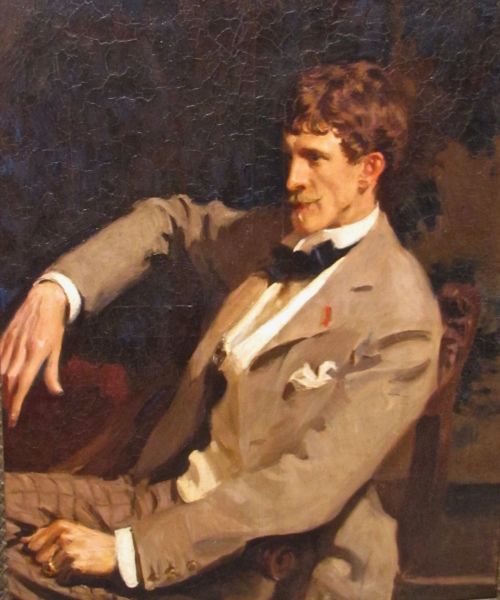

3. Ellen Emmet [Rand], Frederick MacMonnies, 1898-1899, Oil on canvas, 39 ¾ x 32 ¼ in., William Benton Museum of Art, University of Connecticut, Storrs

4. Ellen Emmet [Rand], In the Studio, 1910, Oil on canvas, 44 ¼ x 36 ¼ in., William Benton Museum of Art, University of Connecticut, Storrs

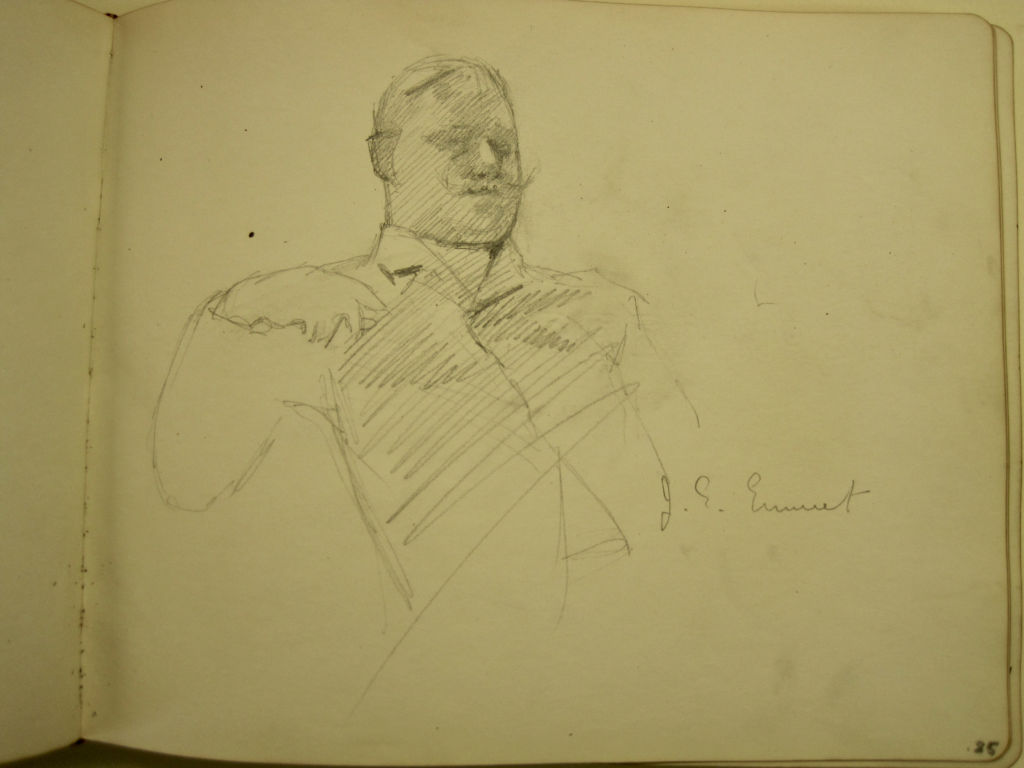

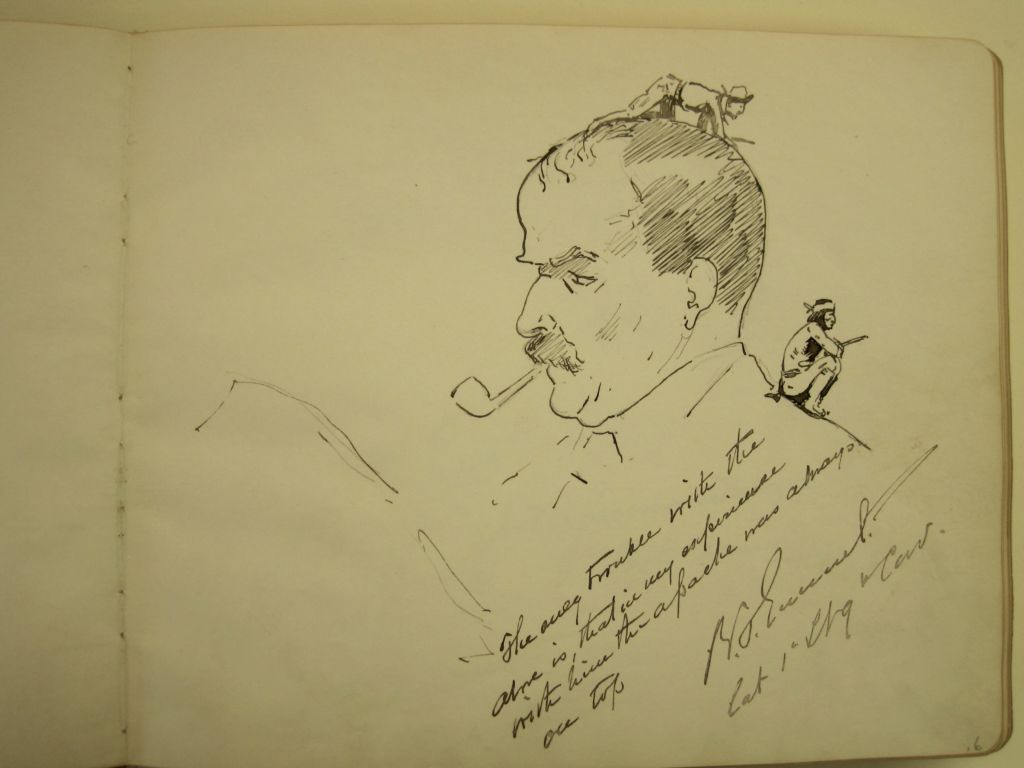

5. Jane Erin Emmet, Frederick Remington, undated. In Remington’s album People I Know, Frederick Remington Art Museum, Ogdensburg, New York.

Ellen Emmet’s extended family included artists, writers, and intellectuals. The philosopher-psychologist William James and his brother, the novelist Henry, were relatives; Henry James dubbed Bay his “paintress-cousin.” In turn, she had three first cousins who also were artists: Rosina Emmet Sherwood, Lydia Field Emmet, and Jane Erin Emmet de Glehn. The latter drew a portrait sketch of Remington that is found in his friendship album People I Know. Remington knew the Emmets well; at least, thirty-three diary entries chronicle visits with an Emmet family member. A favorite of his was Ellen Emmet’s cousin Robert Temple Emmet, a graduate of West Point who had served with the 9th Cavalry Regiment of the Buffalo Soldiers in New Mexico and who was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1879. A caricature of Colonel Emmet by Remington appears in People I Know.

6. Frederick Remington, Robert Temple Emmet, undated. In Remington’s album People I Know, Frederick Remington Art Museum, Ogdensburg, New York.

7. Ellen Emmet [Rand], Richard Harding Davis, 1901, Oil on canvas, 40 x 29 ¼ in., William Benton Museum of Art, University of Connecticut, Storrs

Always as yet a little brusque in her manner of approaching a character, her sincere realism is a relief after [a more] stylistic painter’s work. She will not be sought out to portray clothes and settings. She will paint men solidly and with increasing insight . . . charm is not one of Miss Emmet’s characteristics usually . . . but all the work is so downright honest that it is refreshing (“Art Notes,” The Independent 62 (March 21, 1907): 651).

Unfortunately, Frederic Remington never did get his “crack at immortality” by being portrayed by her.

As I was writing this blog about Ellen Emmet Rand, I was delighted to discover that the William Benton Museum of Art at the University of Connecticut is focusing new attention on this neglected, but significant, artist by having organized the exhibition The Business of Bodies: Ellen Emmet Rand (1875-1941) and the Business of Portraiture. The exhibit recently opened and is on view until March 10, 2019. Professor Alexis L. Boylan, the show’s curator, tells me that a book of essays about the artist will be published next year.

8. Ellen Emmet Rand, Self-Portrait, 1927, Oil on canvas, 30 X 24 in., National Academy of Design, New York

Leave A Comment