*Iconic Western painter Frederic Remington began his career drawing black and white illustrations for the most popular magazines in America. Yet he yearned to be known as an artist, not just an illustrator, and he strategically drew inspiration from the museums and art galleries of New York City. Friends with American Impressionist Childe Hassam and a number of young American painters, Remington first saw the work of Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro and other modern French painters at the newly opened Durand-Ruel Gallery whose owner became an early proponent of French Impressionism.

Following over a century of tradition, French Academic art valued paintings of history, religion, and mythology. The Impressionists challenged this trope by painting modern life. They were the first generation of artists to have access to newly-invented bright, artificial paints available in new collapsible metal tubes that freed them to work out of doors. Using visible, flickering brushstrokes, they attempted to register their sensations to light and weather.

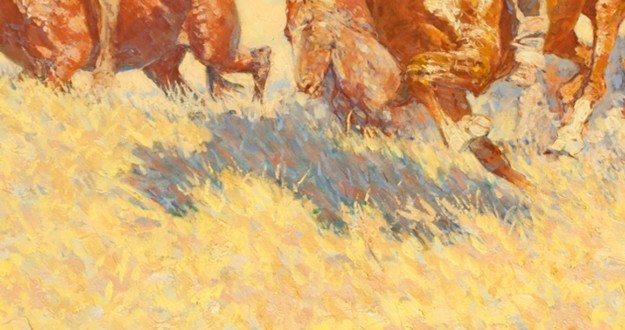

When Remington first saw this new art, he declared, “I’ve got two maiden aunts . . . who can knit better pictures than that.” Yet, Remington quietly admired the brighter palette, their theories of representing light, color and shadow. He started incorporating some of these techniques into his own work while maintaining his favored subject matter–his memories of the American West frontier. For instance, in this detail of Buffalo Runners—Big Horn Basin, the shadows under the horses are the complimentary color of the dried grass in the foreground. Likewise, he knitted into the shadow small strokes of the reflected reddish-brown of the horses. Both of these ideas Remington adapted from the Impressionists.

Detail, Frederic Remington | Buffalo Runners – Big Horn Basin | 1909 | Oil on canvas | 30 1/8 x 51 1/8 inches

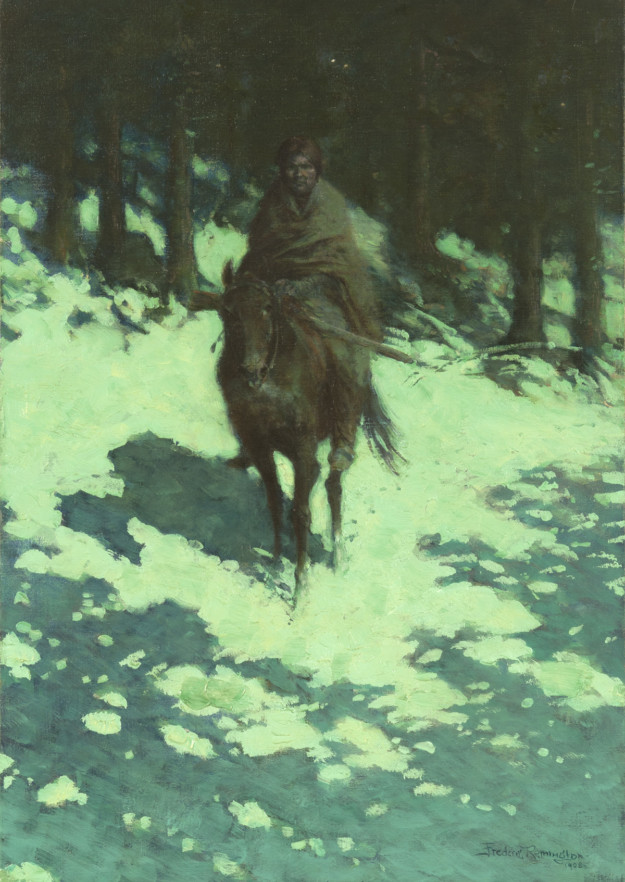

At the same time, intrigued by the concept of painting believable night scenes, first introduced to American audiences by James McNeill Whistler, Remington attempted his own night scenes, or nocturnes. By eliminating detail, limiting his palette to black, brown, blue, green and white, Remington gave us atmospheric paintings that became some of his most famous and cherished works. Remington stated that he did his most difficult work outside the painting, and by doing so, he hoped to challenge the viewer to use their imagination.

In the painting, A Figure of the Night, Remington framed the rider and horse with a dark, impenetrable forest in the background and the shadows of unseen trees in the foreground. The bright blue green ground reads as snow lit by moonlight. The foreground shadows suggest the loneliness of the rider’s situation and the potential of hidden dangers ahead.

Frederic Remington | A Figure of the Night (The Sentinel) | 1908 | Oil on canvas | 30 x 21 1/8 inches

Today, Remington’s paintings serve as visual source material for modern film-makers and historians of the Western frontier. But Remington deserves to also be acknowledged as a fine, turn-of-the-century American artist who adapted ideas and techniques from other modern artists while remaining true to his passion for the West.

Frederic Remington, The Dry Camp, 1907, Oil on canvas, 27 3/8 x 40 inches

*Guest blog post written by Deborah Reed, independent scholar and presenter of Monet to Remington: Impressionism’s Influence on Remington’s Late Paintings (a lecture presented at the Sid Richardson Museum, November 2015).

Thanks for these tidbits of information. Reading your blogs helps me to not only learn more about Art Paintings but also the Artist. I am learning more all the time about how to really appreciate Art Paintings and the Artist who painted them. Thanks again.

The blog is really an extension of the Sid Richardson Museum and helps fulfill our mission, which is to engage, educate, and inspire visitors (and readers) to find meaning, value, and enjoyment in art of the American West. I’m glad you learning new insights and feeling more connected with the art and artists in our collection!

The “Monet to Remington” presentation was so insightful. Thank you for helping me appreciate Remington’s later work all the more!

I agree, Nancy! Deborah Reed put together a fantastic presentation for the Sid Richardson Museum. She really helped me think about Remington and his work in a new way. Glad you enjoyed the program!