One of the themes of our current exhibit, Night & Day: Frederic Remington’s Final Decade, is that of Remington’s progression from illustrator to fine artist. During his time, in the late 19th and early 20th century, illustrated magazines and books garnered wide popularity in the US, and thus earned the moniker the Golden Age of Illustration. Despite their popularity, being an illustrator did not carry the same status as that of a fine artist painter.

In general, illustration during Remington’s time depicted a narrative from the accompanying text, often executed in black and white. Fine art painting was believed to require imagination and allowed for the exploration of the nuances of light and color on a larger scale. Illustrations were seen to enhance printed material, whereas paintings occupied their own space. Although Remington excelled as an illustrator, he wanted to be taken seriously. He wanted to be known as a painter.

Frederic Remington | The Cow Puncher | 1901 | Oil (black & white) on canvas | 28 7/8 inches x 19 inches

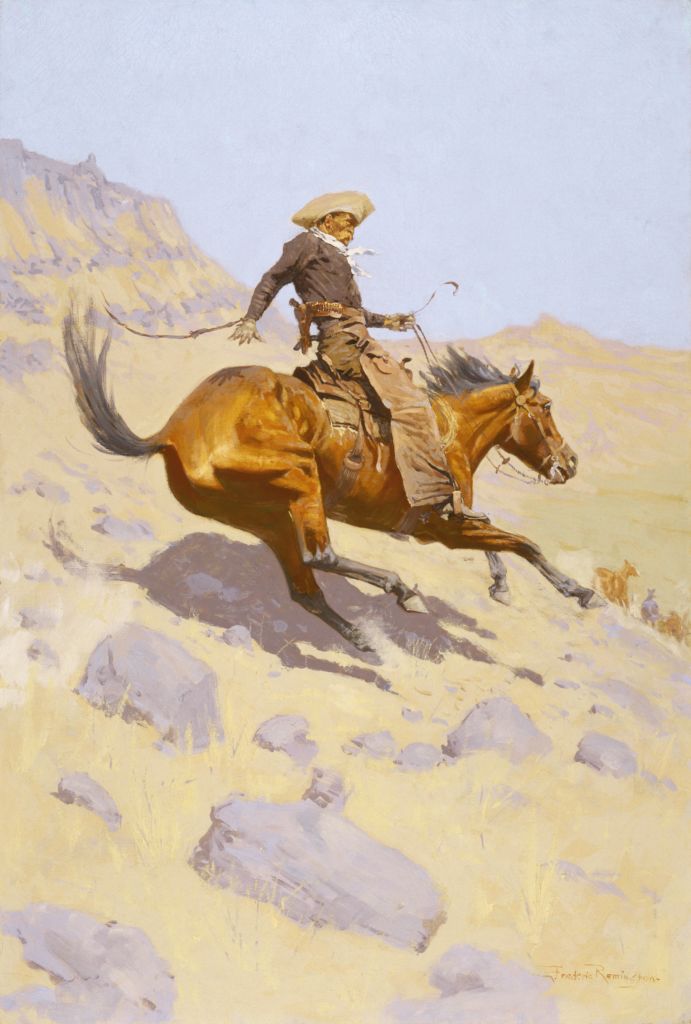

Frederic S. Remington | The Cowboy | 1902 | Oil on canvas | Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, Amon G. Carter Collection | 1961.382

While working as a successful illustrator, Remington was also exhibiting his paintings. Between the two media, Remington was working with similar imagery – the American cowboy. There was a general awareness that the American West of a certain era was now gone, and the cowboy was an old subject. The cowboy had become a mythic image of the West. Remington once wrote a friend that the, ”…cowboy is as dead as the dodo.” Therefore, the public began to perceive Remington as painting history, with critics referring to the artist as the pictorial historian of the West.

He rides the earth with hoofs of might

His is the song the eagle sings;

Strong as the eagle’s, his delight,

For like his rope, his heart hath wings.

-Owen Wister, accompanying Remington’s painting, which appeared on the cover of Collier’s Weekly, September 14, 1901

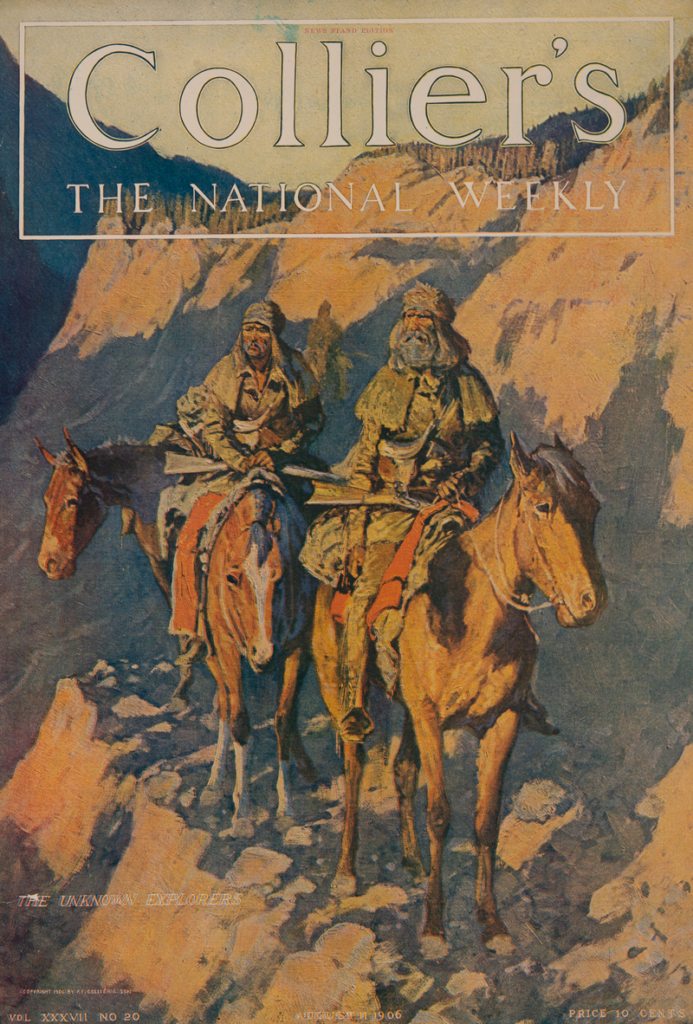

Frederic Remington | The Unknown Explorers | 1908 | Oil on canvas | 30 x 27.25 inches

Frederic Remington | The Unknown Explorers | color halftone | ca. 1905 | Collier’s Weekly, August 11, 1906, cover | Frederic Remington Art Museum, Ogdensburg, New York

As Remington reached what becomes the last decade of his career (unbeknownst to Remington), his paintings began to exhibit a noticeable shift in style. In 1899 Remington viewed an exhibition that included night time paintings by Tonalist painter Charles Rollo Peters and the American Impressionist Childe Hassam. Remington was good friends with Hassam, who had suggested Remington try painting night time compositions. Today, many of Remington’s night paintings are known by scholars as nocturnes, a title derived from American artist James Abbott McNeill Whistler (who originally derived the term from the field of music to suggest a moody, quiet quality). Remington, ardent about his distaste for Whistler’s work, referred to his own night time paintings as “moonlights.” It is these “moonlights” that helped establish Remington’s reputation as a fine artist.

Dr. Mark Thistlethwaite explored Remington’s career transformation in a recent lecture at the museum, which can be viewed in its entirety here.

Leave A Comment