While he is better known as a painter, Charles M. Russell was as skillful with clay as he was with paint. As a young boy, he showed natural talent for modeling the heroes and animals of his dreams. Family lore has it that his first clay sculpture was a bear, modeled from clay the four-year-old scraped from his shoes.

Critics praised the accuracy of Russell’s observation and animated naturalism of his subjects in both paint and bronze, but many contemporaries considered him more gifted as a sculptor. While Russell’s bronzes lack the refined unity seen in works by his academically trained colleagues, they have a vitality all their own. Russell told an interviewer in 1911 that a choice between painting and modeling would be hard to make, but that perhaps modeling would be his choice if he were forced to decide between the two.

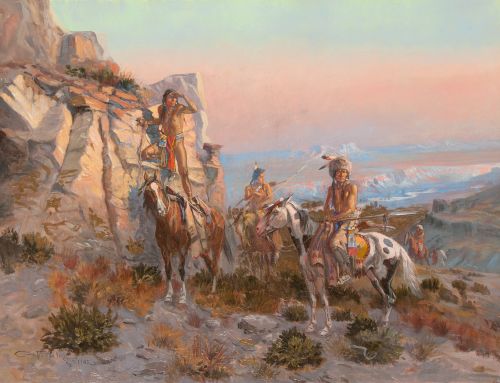

The Sid Richardson Museum currently displays five Russell bronzes on loan from private collections, selected to complement the strength of Russell’s American Indian themes represented in the Museum’s collection. Three bronzes depicting American Indian rituals, The Scalp Dancer (1914), The Snake Priest (1914), and Smoking with the Spirit of the Buffalo (1915) are examples of smaller works Russell created for a public eager for decorative and utilitarian bronzes.

Smoking with the Spirit of the Buffalo Modeled 1914 | Roman Bronze Works cast # unknown, 1915 | Private Collection

At the turn of the twentieth century, access to and the popularity of small bronze pieces suitable for home display were in part fueled by the increase of American foundries. Small parlor pieces were available from galleries, Tiffany & Company, and Gorham. Bronzes such as Smoking with the Spirit of the Buffalo offered patrons insight into American Indian life and the key role that the buffalo played— “…his robe housed and clothed them, [and] his flesh was food,” said wife Nancy Russell. She explained that “the Indians believe all animals live again in another world…, so when smoking, the Indian often prayed to the buffalo, holding his pipe to the skull and asking that his kind might always be plenty.” Russell was inspired to create this bronze following a visit in 1888 with Alberta’s Blood Indians, who believed that the buffalo would return from the underground where they had taken refuge after the white man had been driven out of the Indian country, and the Medicine Man’s prayers would hasten that event.

The Snake Priest | Modeled 1914 California Art Bronze Foundry cast # unknown, 1914 | Private Collection

The Snake Priest depicts a squatting American Indian, thrusting at a coiled snake with a snake whip, an important accessory to the Hopi Snake Ceremony. An unpublished biography of Charles Russell, written by Daniel Conway from information provided by Russell’s wife, explains that the figure is Lomanakshu, Chief of the Mishongnovi Snake Fraternity. While Russell might not have ever seen such a ceremony, he may have been familiar with a report about them by George A. Dorsey, published in the “Field Columbian Museum Anthropological Series”, June 1902. Dorsey witnessed a ceremony in Mishongnovi, a village in the Southwest. According to Dorsey, the whip was made of a shaft of wood about nine inches long, painted red, to which were fastened two long eagle tail feathers by many wrappings of buckskin thong. The sculpture seems to capture the moment when Lomanakshu exerts control over the coiled reptile.

The Scalp Dancer | Modeled 1914 Benjamin Zoppo Foundry cast #6, 1914 Private Collection

This small figure of a dancing Indian wearing a breech cloth, with his flowing braids and a wolf skin trailing at his side, suggests the low, side-to-side leaping motions made by Crow warriors dancing in celebration of successful coups taken against an enemy. This subject is one of several smaller decorative, utilitarian bronzes. The bookends and ashtrays were likely created at wife and business partner Nancy’s urging, who saw the potential appeal of affordable sculptures, believing they would reach a broader market than the more expensive paintings.

These bronzes really do set a full scene. It almost seems as if the dancer is going to jump right off the platform in The Scalp Dancer. It’s strange how the general public cares more about painting than sculpture.

Agreed! The Scalp Dancer is one of my favorites of the bronzes in the exhibit.