Long before the silver screen mythologized the American West, Charles M. Russell had already etched it into bronze and canvas. But in the twilight of his life, Russell wasn’t just painting cowboys. He was rubbing elbows with movie stars.

When Charlie and Nancy Russell began wintering in Southern California in 1920, they weren’t merely escaping the Montana cold. They were entering a lively, evolving cultural hub where artists, filmmakers, and writers mingled freely. And where the Old West met the New Hollywood.

Russell’s ties to Tinseltown may sound like an unlikely chapter in the life of a Western artist, but the connections ran deeper than you might expect. Charlie had long been acquainted with celebrities of the day, stage actor William S. Hart and cowboy humorist Will Rogers among them. But California introduced him to a new cast of characters, including silent film legends Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford.

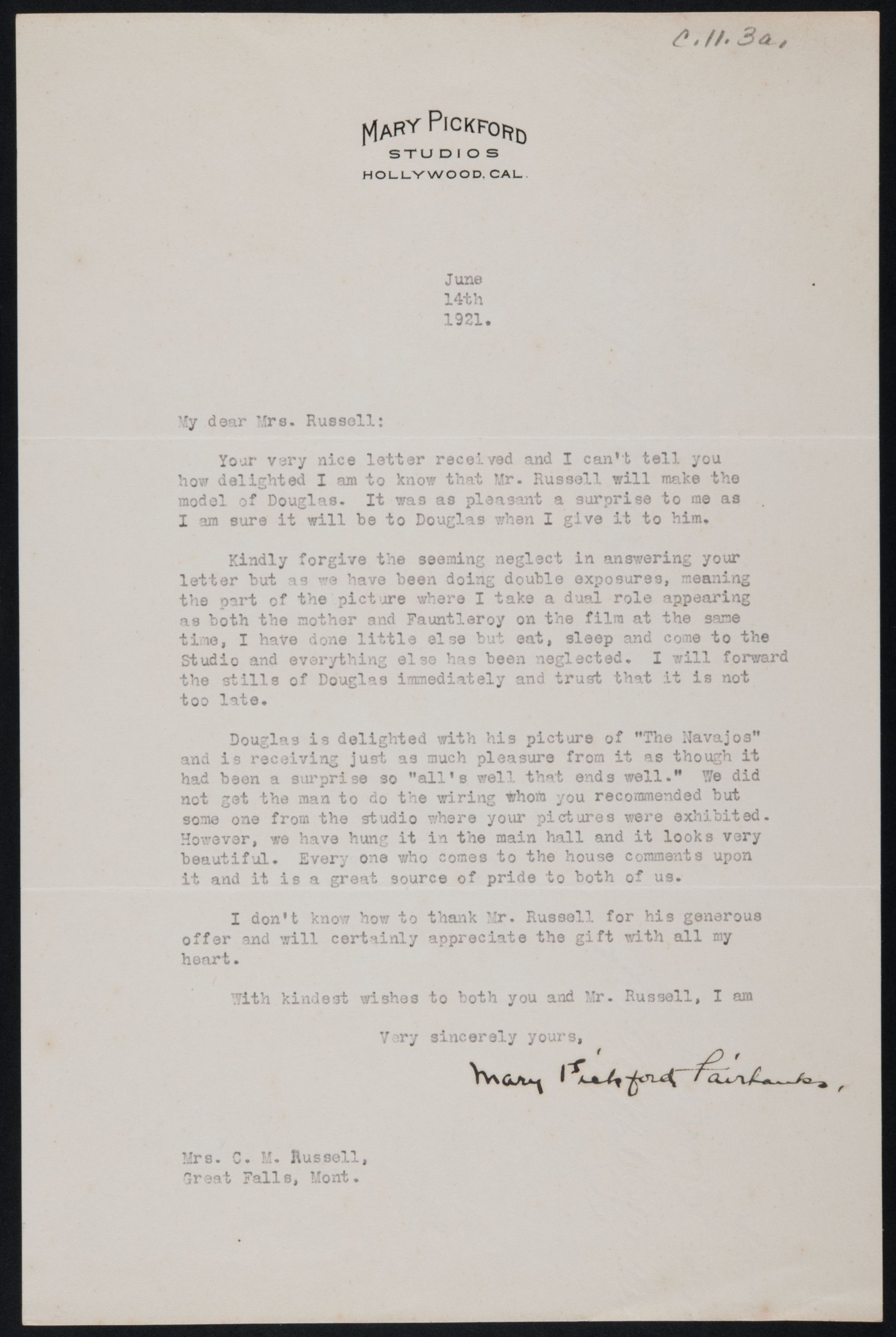

It was in 1921 at an exhibition of Russell’s work at the Kanst Gallery in Los Angeles where this dynamic duo fell for the same painting: The Navajos. Both attempted to buy it as a surprise gift for the other. The mix-up was resolved with good humor, as Mary later wrote to Nancy:

“Douglas is delighted with his picture of ‘The Navajos’ and is receiving just as much pleasure from it as though it had been a surprise, so ‘all’s well that ends well.’”

That painting went on to hang in the entry hall of Pickfair, the couple’s legendary estate, before eventually finding its home in the Desert Caballeros Museum in Wickenburg, Arizona.

Copy of Letter from Mary Pickford Fairbanks to Nancy C. Russell, 1921, Gilcrease Museum, Charles M. Russell Research Collection (Britzman), Tulsa, OK, TU2009.39.4828

As their friendships of the Russells blossomed, so too did creative collaborations. Actor Harry Carey introduced Charlie to a young John Ford in 1924. Russell also found kindred spirits in cultural figures like Charles Lummis, an advocate for preserving the heritage of the Southwest. Their shared love for history and storytelling bonded them regardless of medium.

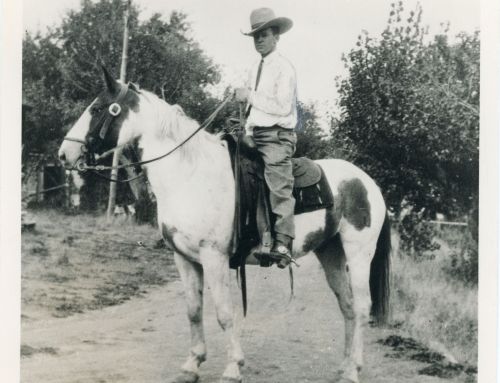

Douglas Fairbanks, Charles Russell, and Nancy Russell | Bain News Service | ca.1920-1925 | Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division; George Grantham Bain Collection

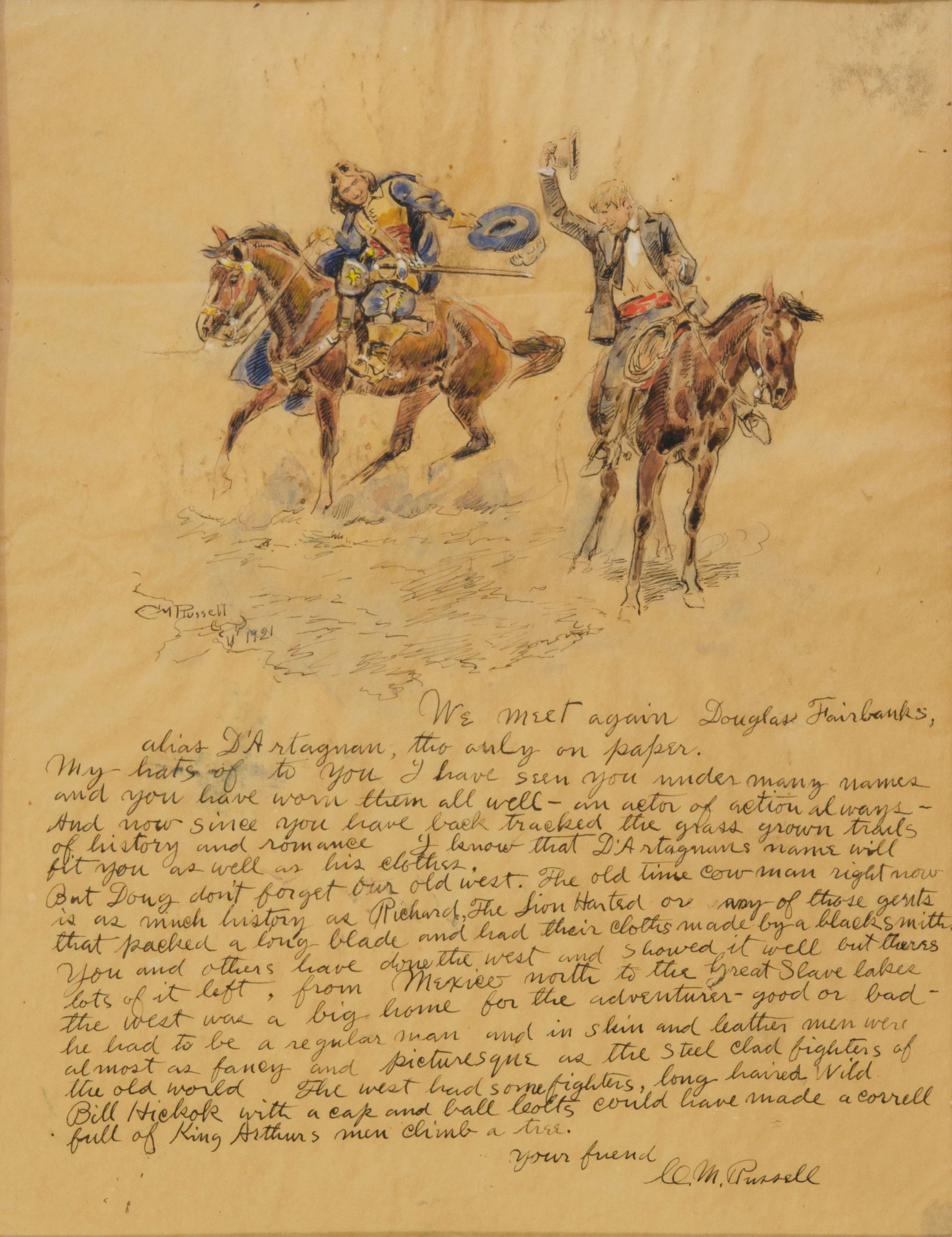

One particularly revealing moment occurred when the Russells were invited to the set of The Three Musketeers, where Fairbanks was filming as the swashbuckling D’Artagnan. Afterward, Charlie penned a letter to the actor, equal parts admiration and friendly challenge:

We meet again Douglas Fairbanks, alias D’Artagnan, though only on paper. My hat’s off to you. I have seen you under many names, and you have worn them all well – an actor of action always. And now, since you have back-tracked the grass-grown trails of history and romance, I know that D’Artagnan’s name will fit you as well as his clothes. But Doug, don’t forget our old West. The old time cowman right now is as much history as Richard the Lionheart, or any of those gents that packed a long blade and had their clothes made by a blacksmith.

You and others have done the West and showed it well, but there’s lots of it left, from Mexico north to the Great Slave Lakes. The West was a big home for the adventurer. Good or bad, he had to be a regular man and in skin and leather, men were almost as fancy and picturesque as the steel-clad fighters of the Old World. The West had some fighters. Longhaired Wild Bill Hickok with a cap and ball Colt could have made a corral full of King Arthur’s men climb a tree.

Your friend,

CM Russell

The letter, complete with a sketch, is a witty, heartfelt reminder of Russell’s mission: to preserve the spirit of the American West with honesty and flair.

Charles Russell, We Meet Again Douglas Fairbanks, 1921, Pen & ink and watercolor on paper, C.M. Russell Museum, Great Falls, MT

Although Nancy later proposed a portrait of Fairbanks as D’Artagnan, Russell never completed a painting. Instead, he sculpted a bronze figure of the actor, head bowed dramatically while seated on horseback, a theatrical gesture befitting its subject. Russell gave Fairbanks the original bronze; Nancy kept a plaster cast that now serves as the basis for the piece on view in our current exhibition.

Charles M. Russell, Fairbanks as D’Artagnan, Bronze, Nelli Art Bronze Works Modeled 1921, cast 1941, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, TX, Amon G. Carter Collection, 1961.80

Today, as American audiences continue to examine how the West is portrayed in film, art, and popular culture, Russell’s work invites reflection on authenticity, representation, and legacy. His art was not just about cowboys and cattle drives. It was about identity, storytelling, and how history is remembered and reimagined.

In a time when Western imagery is being reconsidered through more critical lenses, Russell’s body of work stands as a valuable artifact of both its era and ours. His willingness to engage with different forms of storytelling—and with storytellers themselves—mirrors our current dialogue across media and cultures. The artist’s intersection with early cinema reminds us that American identity has always been shaped by a blend of art, myth, and collaboration.

As you explore our exhibition, we invite you to consider how these friendships and exchanges shaped the broader image of the American West. There’s a rich story behind every piece on display, one that continues to unfold through the voices, artifacts, and images left behind.

Visit the museum to discover how Russell’s vision transcended genre and geography, weaving together frontier and film in ways that still resonate today. And challenge us to consider how the stories we tell reflect the values we carry forward.

Leave A Comment