The Golden Age of American illustration wasn’t limited to popular periodicals of the era. Charles Russell and Frederic Remington also contributed illustrations for different book projects.

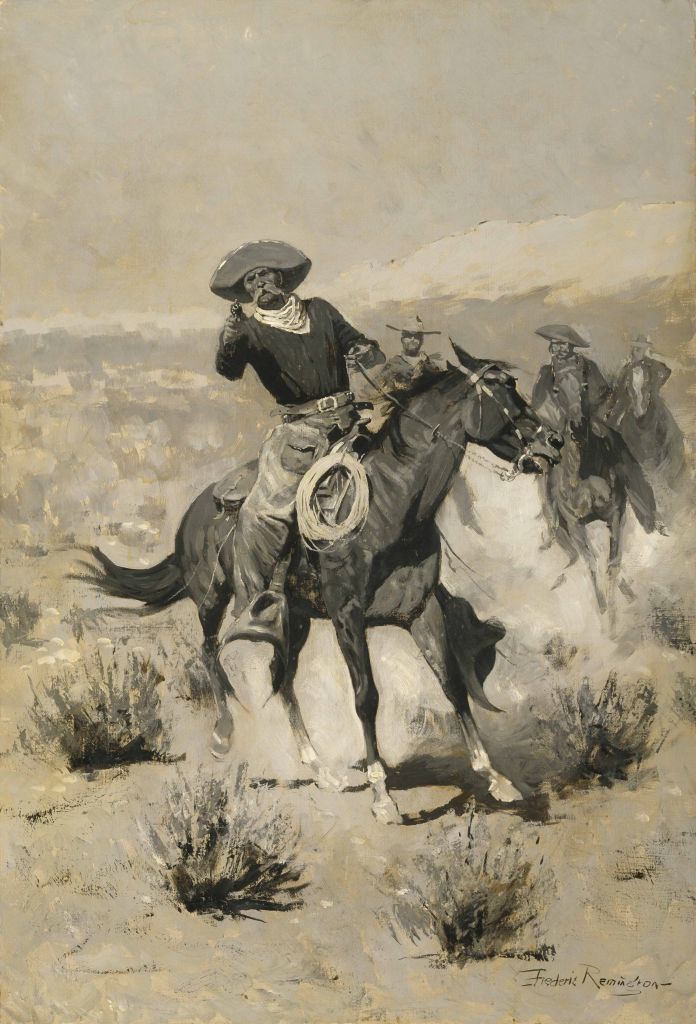

In 1902, Remington painted Days on the Range to serve as the frontispiece for Alfred Henry Lewis’s book Wolfville Days. The scene portrayed in Remington’s canvas relates to the 19th chapter in the book, “When the Stage was Stopped.” In this last section of the book, the narrator describes a long-winded tale about stagecoach robberies and holdups.

In the story, the townspeople of Wolfville devise a scheme to trick one of the suspected bandits, Davis. Just as the group of robbers think they’ve gotten away with preying upon another Wells Fargo coach, the hero of the story, Jack Moore, follows the outlaws into the desert canyons of Tucson to seek justice. Through his painting, Remington has brought the reader into the story, as the mustachioed cowboy on the horse points his revolver in our direction, confronting the viewer in this compelling composition.

Frederic Remington | Days on the Range (“Hands Up!”) | Oil on canvas | ca.1902 | The Hogg Brothers Collection, gift of Miss Ima Hogg, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston | 43.48

Wolfville Days was one of the many volumes Alfred Henry Lewis published about cowboy life in Arizona. The popular humorist and novelist was an educated man, who, like Remington, had travelled west to work as a cowboy when he was young. Though a lawyer by training, Lewis wrote short stories, the success of which led to a career as a journalist working for William Randolph Hearst and writing novels.

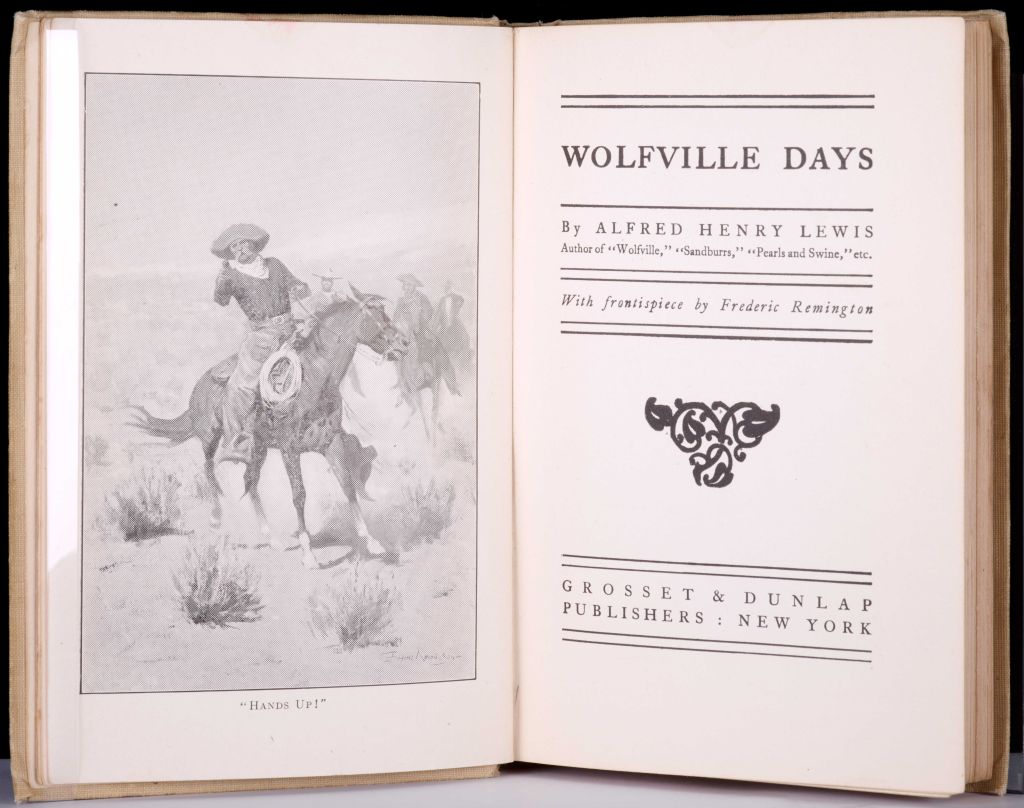

Remington had teamed up with Lewis previously in 1897 for Lewis’s series Wolfville, providing 18 illustrations. By 1902, Remington was concentrating on capturing color in his paintings and, therefore, included only one black and white illustration for this book. The washed-out image made of varying dots that create this halftone pales in contrast to the warm tones and sharp contrasts of Remington’s original painting.

Alfred Henry Lewis | Wolfville Days | 1902 | New York: Grosset & Dunlap Publishers | Copyright, 1902 by Frederick A. Stokes Company

Charles Russell was no stranger to book projects. In August 1910, while at his summer cabin at Lake McDonald in Glacier National Park, Russell began work on a large commission to illustrate a frontier memoir by Carrie Adell Strahorn titled Fifteen Thousand Miles by Stage: A Woman’s Unique Experience during Thirty Years of Path Finding and Pioneering from the Missouri to the Pacific and from Alaska to Mexico.

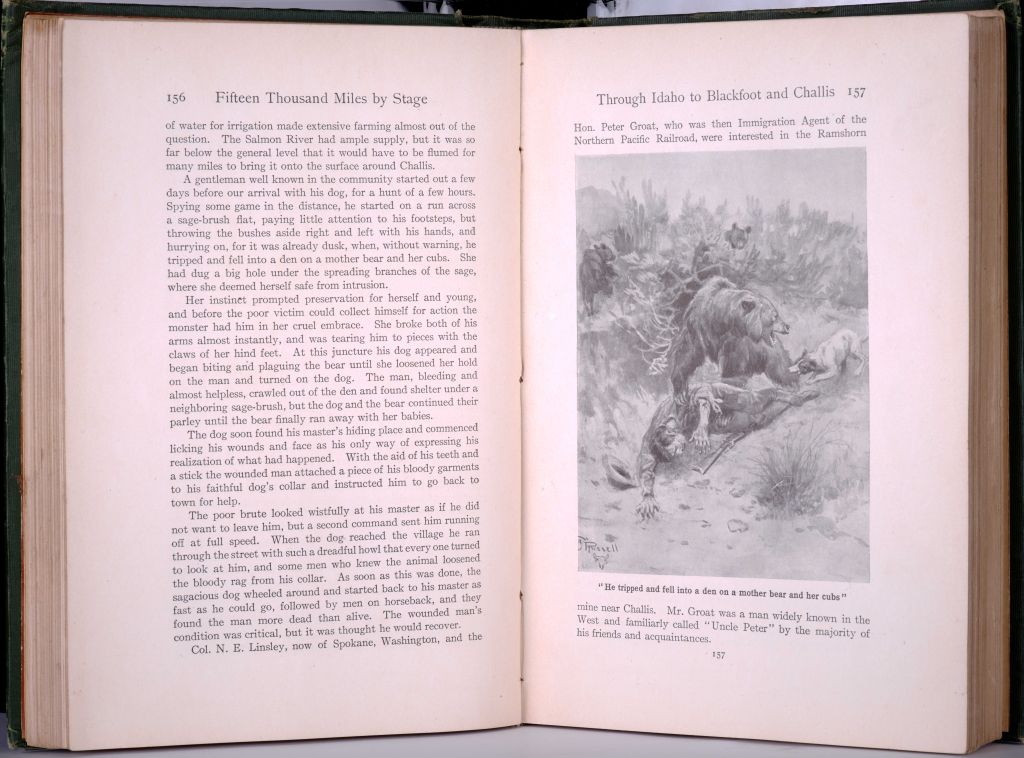

Mrs. Strahorn was told of the incident depicted in this watercolor, which occurred near Challis, Idaho, when a local hunter suddenly encountered a defensive mother bear and her cubs. Whether it was a grizzly bear or a smaller black bear, Mrs. Strahorn doesn’t indicate, but Russell knew a grizzly made a better story. The man barely survived thanks to his brave and faithful hunting dog, who managed to distract the mother bear and cause it and her cubs to flee.

Charles M. Russell | He Tripped And Fell Into A Den On A Mother Bear And Her Cubs | 1910 | Watercolor, pencil & gouache on paper | 17 inches x 14 inches

Carrie Adell Strahorn and her husband Robert Edmund Strahorn were pioneers of travel writing in the Western United States. A week after they were married in 1877, Robert took a job with the Union Pacific Railroad Company as an advertising writer to promote western travel and settlement. Rather than leave Carrie at home to tend to a household, he demanded that the Union Pacific allow her to travel with him. At the time, the Union Pacific was planning a direct connection to the Pacific Northwest and the Strahorns were sent to investigate. The couple traveled mainly by stagecoach, writing books and articles about their adventures pioneering in the Idaho Territory.

Carrie wrote this memoir of her travels based on events and stories she had experienced while traveling in the west. The book contains 350 illustrations, 85 of them provided by Charles Russell: 17 watercolors and 68 pen and ink drawings. While it is assured that Strahorn was proud to have Russell as an important contributor to the illustrations in her book, the halftone reproductions pale in comparison to the original watercolors and drawings.

Carrie Adell Strahorn | Fifteen Thousand Miles by Stage: A Woman’s Unique Experience during Thirty Years of Path Finding and Pioneering from the Missouri to the Pacific and from Alaska to Mexico | 1911 | The Knickerbocker Press, G.P. Putman’s Sons: New York and London

Another illustration project Russell worked on was Stewart White’s Arizona Nights, which features a series of stories loosely connected by the narrative device of different speakers swapping yarns around the campfire at the end of each trail-riding day. Russell’s illustration below – Over the Next Ridge, Therefore, We Slipped and Slid, Thanking the God of Luck for Each Ten Feet Gained – depicts a scene from Windy Bill’s Yarn: Emigrant Pass.

The story begins with the riders and their dogs out on the trails when they are caught in a downpour while looking for shelter for the night. Russell uses a thick application of gouache to create the scene, showing a train of riders picking their way down the mountain side in the driving rain. The misery of the situation is most evident in the faces of the soaked dogs and horses. The search for shelter ends when they finally reach a cave in which they light a fire and stretch out. The rushing waters outside the cave reminds Windy Bill of a story he begins to recount for the others.

Charles M. Russell | “Over the Next Ridge, Therefore, We Slipped and Slid, Thanking the God of Luck for Each Ten Feet Gained” | 1905 | Watercolor | Private Collection

Windy Bill then tells the story of Old Texas Pete who was hoarding the spring water outside Emigrant Pass. Russell illustrates a scene from the narrative in his 1905 watercolor, He Snaked Old Texas Pete Right Out of His Wicky-up, Gun and All, which is also featured in our current exhibition, Remington and Russell in Black and White.

In He Snaked Old Texas Pete…, the action-filled watercolor depicts a scene from one of the stories concerning a selfish and disreputable character named Texas Pete. The man, who was “about as broad as he was long” with “big whiskers and black eyebrows,” discovered a water-hole in the middle of the Arizona desert, set up shop, and began gouging the emigrant traffic en route to California “two bits a head-man or beast” for a drink of water.

Texas Pete was setup in a “wickiup,” which is a shelter or hut made from brush and reeds over a pole frame that was utilized by Indigenous peoples across the West. In Russell’s and White’s day, the word was used to characterize any form of crude, temporary shelter. In the story, Texas Pete would sit outside his canvas shack a Winchester across his lap, and let a crude sign speak for him.

One day two good-hearted cowboys chanced by when an emigrant denied water because he could not meet the price bent down to scoop up a drink for his sick child from an overflow puddle. His thirsty horses chose the same moment to dip into the trough. Texas Pete jumped up and fired, killing one of the horses. Instantly a cowboy grabbed his rope and:

“With one of the prettiest twenty-foot flip throws

I ever see done he snaked old Texas Pete right out

of his wicky-up gun and all. The old renegade

did his best to twist around for a shot at us; but it

was no go; and I never enjoyed hog-tying a critter

more in my life than I enjoyed hog-tying Texas Pete.”

Charles M. Russell | He Snaked Old Texas Pete Right Out of His Wicky-up, Gun and All | 1905 | Watercolor, pencil & gouache on paper | 12 3/8 inches x 17 1/8 inches

How did Russell end up illustrating these stories? In December 1903, after visiting family in St. Louis for the Christmas holidays, Charles and Nancy Russell boarded a train for his first visit to New York. During that fruitful trip, which lasted several weeks, the Russells met several artists who introduced them to the art editors of some of the leading magazines of the day. One of these magazines was McClure’s, which commissioned Russell to provide illustrations for a series of stories by Stewart Edward White titled Arizona Nights.

However, when White published a book version in 1907 of the McClure’s series of stories, the art director replaced Russell’s images with works by N.C. Wyeth, another great Golden Age era illustrator. Howard Pyle, who had served a brief stint as McClure’s art director, was a mentor to Wyeth and perhaps preferred Wyeth over Russell. Pyle’s distaste for the cowboy artist seemed to have stuck, as a couple of years later, Edgar Beecher Bronson had written a story and asked McClure’s to select Russell as illustrator, but the magazine refused.

Focusing on these grayscale works featured our current exhibit – Remington and Russell in Black and White – provides a rare opportunity to view the original illustrations by Remington and Russell next to their printed counterparts and compare how the visual narrative translates from painting to page.

[…] such stories on display were written by men. (A noted exception in the museum exhibit is one of the illustrations Russell contributed to Carrie Adell Strahorn’s book, Fifteen Thousand Miles by Stage: A Woman’s Unique Experience during Thirty Years of Path Finding […]