The Golden Age of American Illustration began in the 1880s and lasted into the mid-twentieth century. During this time, New York replaced London as the center of illustrated periodicals published in the English language. Technological advances allowed for inexpensive yet high quality images to be reproduced easily and distributed to a wide audience through magazines like the popular Harper’s Magazine, Century Magazine, and Collier’s.

And Frederic Remington and Charles Russell were on hand to contribute their art! Remington’s first commercial illustration appeared in an 1882 issue of Harper’s Weekly, and just a handful of years later, Russell’s first illustration was featured in Harper’s in May of 1888.

The oldest continuously published general-interest monthly in America, Harper’s Magazine debuted in June 1850. Through long-form narrative journalism and essays, Harper’s seeks to explore the issues that drive our national conversation and is celebrated for such features as the iconic Harper’s Index. By the early twentieth century, the magazine had published the work of American artists and writers like Horace Greeley, Winslow Homer, Henry James, Jack London, John Muir, and Mark Twain – alongside the illustrations of Remington and Russell. And today, Harper’s Magazine can boast archives of published writings from distinguished names like Annie Dillard, Barbara Ehrenreich, David Foster Wallace, and Tom Wolfe. Featured in our current exhibition, Remington and Russell in Black and White, are several artworks by Remington used as illustrations in Harper’s.

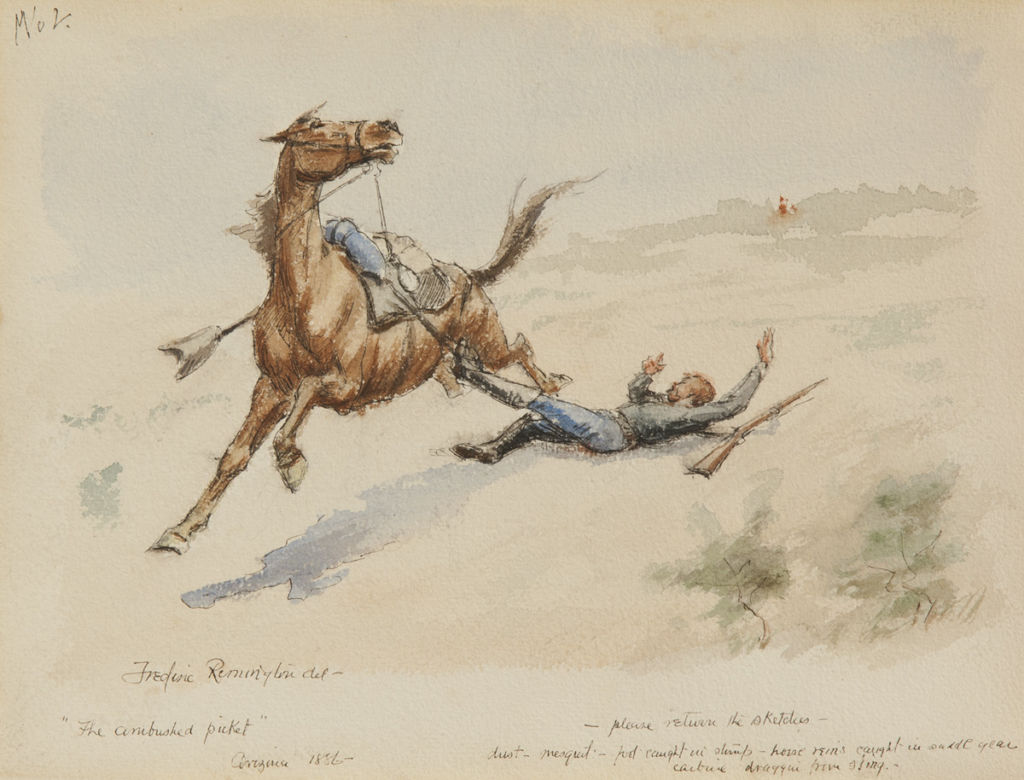

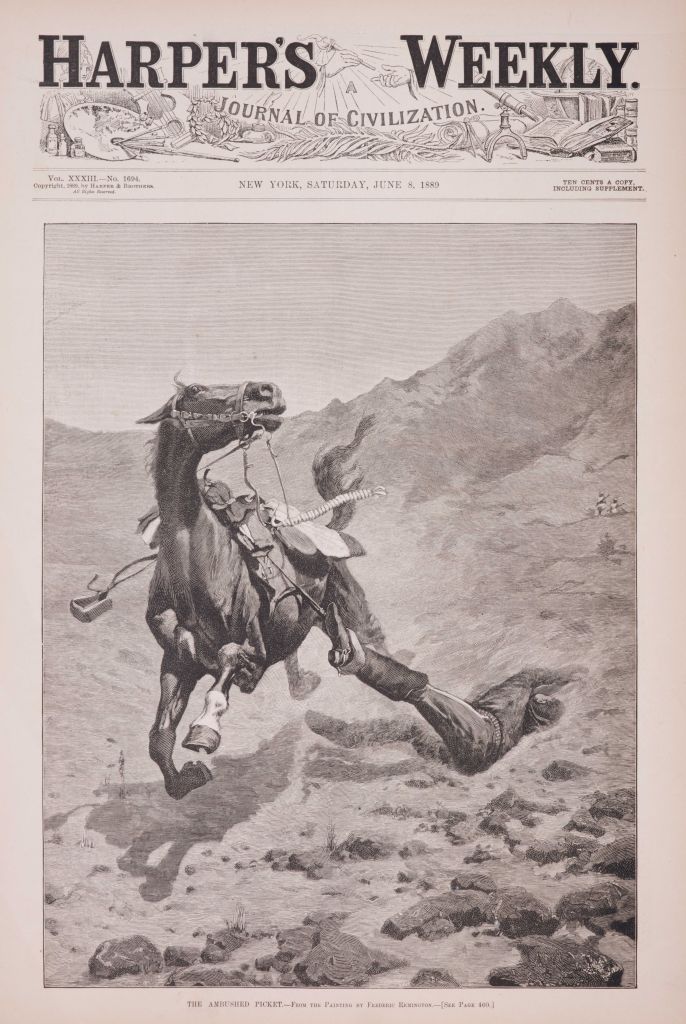

One of the earliest work in the exhibit is from 1886, when Remington was in Arizona as a correspondent for Harper’s Weekly, covering the Geronimo campaign. The artist patrolled with Company K of the Tenth Cavalry, an African-American regiment, in the Santa Catalina Mountains north of Tucson. But Remington saw no action. Although seeming to be eyewitness accounts, his sketches are based on imagination and tales recounted by the troops with whom he traveled. The Ambushed Picket was sketched on that trip but was not used right away. It appeared three years later as a reworked cover for Harper’s Weekly, June 8, 1889.

Frederic Remington | The Ambushed Picket | 1886 | Pencil, pen & ink, watercolor on paper | 9 x 11 7/8 inches

Frederic Remington, The Ambushed Picket, Harper’s Weekly, June 8, 1889, Copyright 1889 by Harper & Brothers

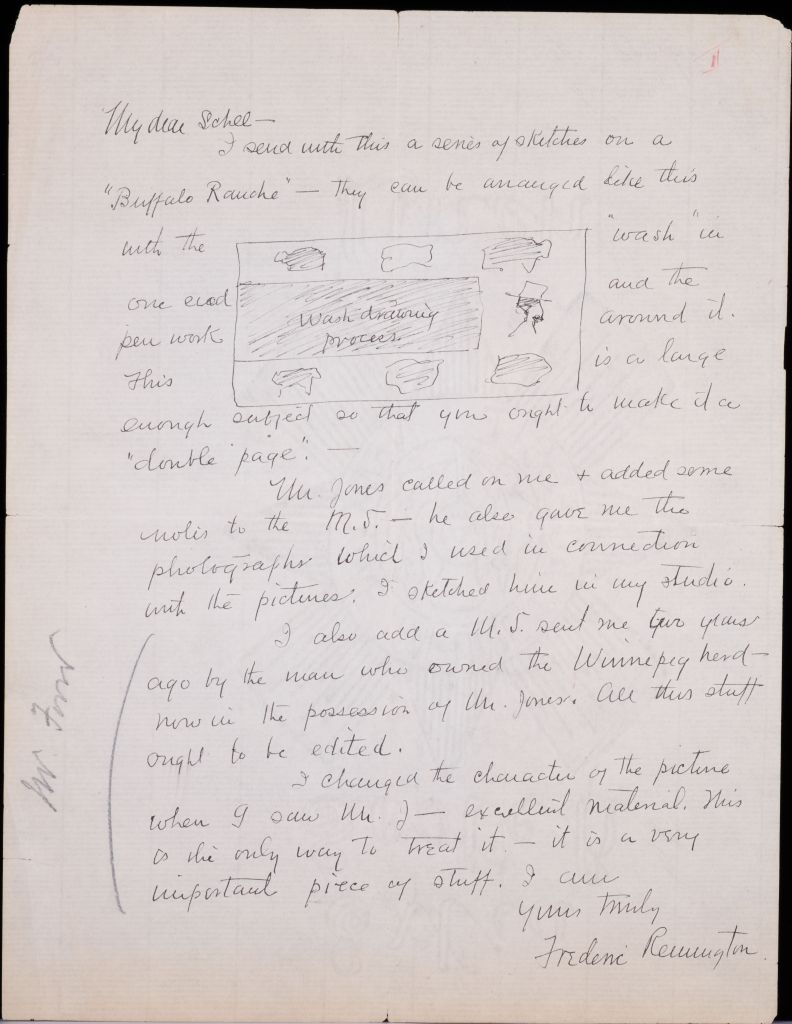

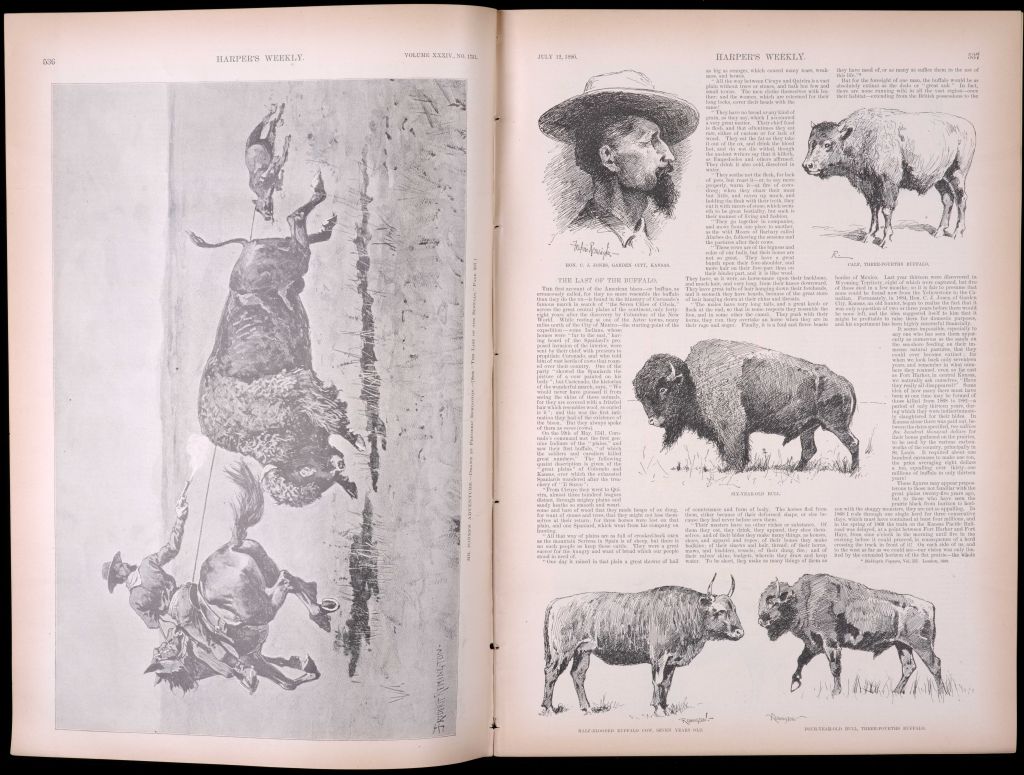

Remington was often in communication with the magazine about his illustrations, as demonstrated in a letter the artist wrote to Harper’s Weekly art director and editor Fred Schell in January 1890. In this note, Remington proposes a double page layout of text and sketches for an article that would eventually be published in July titled “The Last of the Buffalo.” Take note of the changes between the final layout and Remington’s initial suggestions sketched out in his letter!

Frederic Remington, Letter from Remington to Fred B. Schell, 1890, Sid Richardson Museum, 1996.2.1.

My dear Schell,

I send with this a series of sketches on a “Buffalo Ranche”—They can be arranged like this with the “wash” in one end and the pen work around it. This is a large enough subject so that you ought to make it a “double page.”—Mr. Jones called on me & added some notes to the M.S.—he also gave me the photographs which I used in connection with the pictures. I sketched him in my studio.

I also add a M.S. sent me two years ago by the man who owned the Winnipeg herd—now in the possession of Mr. Jones. All this stuff ought to be edited.

I changed the character of the picture when I saw Mr. J—excellent material. This is the only way to treat it.—it is a very important piece of stuff. I am

yours truly

Frederic Remington

“The Last of the Buffalo” by Henry Inman, Illustrated by Frederic Remington, Harper’s Weekly, July 12, 1890, pp.536-539, Copyright 1890 by Harper & Brothers

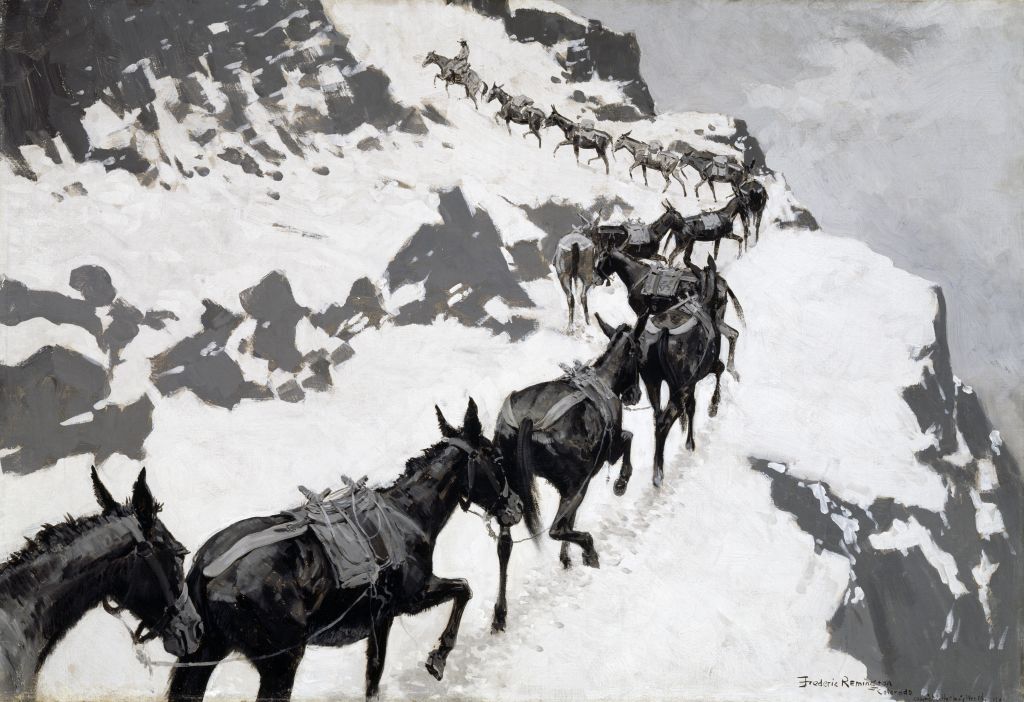

Remington’s ca. 1901 painting The Mule Pack was the artist’s last image to be featured in Harper’s Weekly, ending a fifteen-year working relationship with the magazine. This artwork was made following Remington’s trip 1900 trip to Colorado and New Mexico and exhibits the loose brushwork and limited detail that will characterize Remington’s work in the final decade of his life. Across this canvas, expanses of white paint are interrupted with abstract patches of gray that read as rock formations, while a snaking line of pack mules make their way up the treacherous slope.

The painting received a two-page spread, and it did not accompany a text, article, or story, foreshadowing the relationship that the artist would develop with Collier’s Weekly in 1903.

Frederic Remington, The Mule Pack, ca. 1901, oil on canvas, The Hogg Brothers Collection, gift of Miss Ima Hogg, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 43.56

Collier’s began publication in 1888 and changed its name to Collier’s Weekly in 1895. (While the name was shortened to “Collier’s” in the early 20th century, the magazine continued to be published weekly until it ceased publication in 1957.) From the beginning, Collier’s was a general interest magazine and established a reputation as what Teddy Roosevelt described as “muckraking journalism,” focusing on social reform. This approach had great impact, resulting in such changes as the reform of child labor laws, slum clearance, and women’s suffrage. For example, Upton Sinclair’s 1905 Collier’s article, “Is Chicago Meat Clean?,” encouraged the US Senate to pass the Federal Meat Inspection Act of 1906, which ensured sanitary conditions for meat processing. Other notable authors who contributed writings to the magazine included F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ray Bradbury, Willa Cather, Sinclair Lewis, Kurt Vonnegut, and the Western writers Zane Grey and Louis L’Amour.

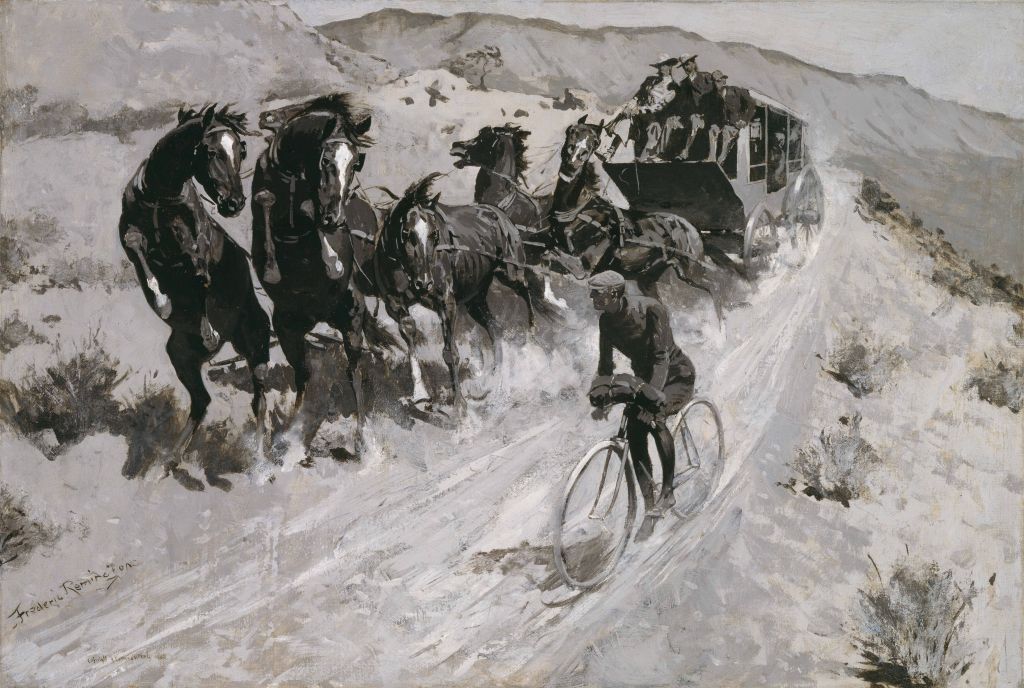

Remington’s 1900 painting “The Right of the Road” – A Hazardous Encounter on a Rocky Mountain Trail, was published in a September 1900 issue of Collier’s Weekly following a trip he made to Colorado. In this scene, Remington pits the mythic stagecoach against a modern mode of transportation, the bicycle. Although the Overland Stage Line was long gone by 1900, the artist imagines a group of frightened stagecoach horses rearing away from the cyclist as he overtakes the team on a narrow mountain road. It’s ironic that Remington chose such a contemporary subject despite his disdain for the modernization of the west. While traveling through Colorado, Remington had written to his wife, “Shall never come west again—It is all brick buildings—derby hats and blue overhauls—it spoils my early illusions—and they are my capital.”

Frederic Remington, “The Right of the Road” — A Hazardous Encounter on a Rocky Mountain Trail, 1900, Oil on canvas, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, Amon G. Carter Collection, 1961.246

Remington also made illustrations for Century Magazine, which was established in 1881 to educate the public with illustrated articles on history, science, and literature over its duration until 1930. Featured in our current exhibit, Remington’s 1897 painting Hello, Jose! (Unexpected Guest) served as the only illustration to the short story, “A Man and Some Others,” written by Stephen Crane for The Century Magazine set in Southwest Texas about a conflict between sheepherders. Remington takes his cue from Crane’s descriptive setting, “Dark mesquit[e] spread from horizon to horizon. There was no house or horseman from which a mind could evolve a city or a crowd. The world was declared to be a desert and unpeopled.”

Frederic Remington, Hello, Jose! (Unexpected Guest), 1897, oil on canvas, Private Collection

In the 1880s, Century Magazine was the leading American periodical of the period, with about 250,000 subscribers. That’s a lot of eyes on Remington’s illustrations! The magazine was renowned for its illustrations and was quite influential, with contributors like Theodore Roosevelt (who even published an article while serving as President!) and Booker T. Washington. However, by 1900, Century Magazine lost nearly half of its initial circulation and suffered due to competition from other cheaper magazines. It was the last major periodical to incorporate photographic illustrations in 1889 and by 1925, illustrations were eliminated.

Our current exhibit – Remington and Russell in Black and White – temporarily revives the Golden Age of Illustration with a look back at a time when Remington and Russell’s works were widely circulated. Pairing the artworks paired with their printed counterparts, the exhibit provides museum visitors the opportunity to experience each artist’s illustrations in a similar fashion as their original audience. Come see for yourself!

[…] Golden Age of American illustration wasn’t limited to popular periodicals of the era. Charles Russell and Frederic Remington also contributed illustrations for different book […]