Scholars consider Frederic Remington to be one of the most copied American artists. While compiling a catalogue raisonné[1] of Remington’s paintings, the review committee examined nearly 500 two-dimensional works. Of those submissions, only 22% were deemed original. The rest were copies, fakes, and forgeries.

What’s the difference between a fake, forgery, or copy? A fake is a painting that does not relate to any known Remington work but is given a fraudulent Remington signature and is of a subject that might have interested him. A forgery occurs when someone takes an artist’s work, paints out his or her signature, and signs the forged signature of another artist. A copy is a reproduction of a known Remington painting but painted by someone else, with a false Remington signature.

The issue of fakes and forgeries is something that is dealt with frequently in the art world. The current system for authenticating works relies on a three-tier approach of connoisseurship (an expert verifying that the work reflects the artist’s style and technique), provenance (the history of an artwork’s ownership) and scientific analysis done by conservators like Claire Barry, Director of Conservation at the Kimbell Art Museum.

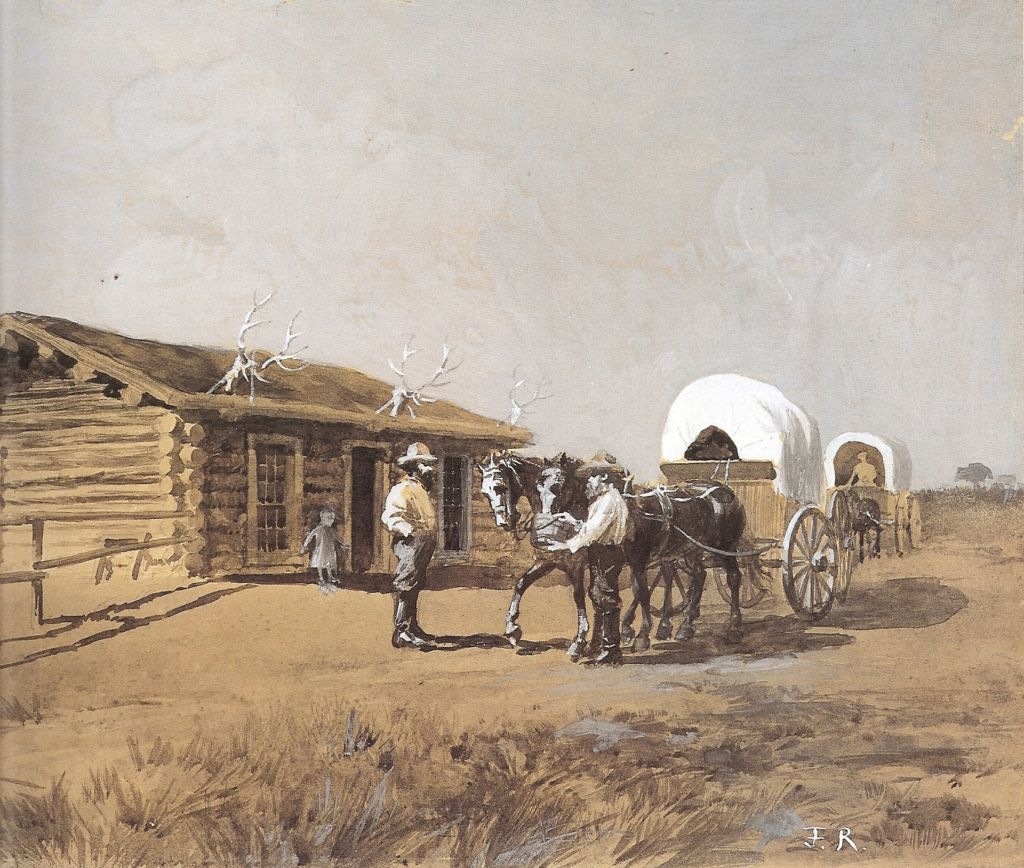

The Way Post | attributed to Frederic Remington | ca. 1881 | Watercolor and gouache on paper

In preparation for the Sid Richardson Museum’s focus exhibit, Frederic Remington: Altered States, Ms. Barry examined The Way Post, a watercolor & gouache painting currently attributed to Remington. However, scholars as well as the museum staff, question the painting’s authorship. The work is dated circa 1881, just at the beginning period of the artist’s career at a time when Remington made his first trip West to Montana. Conservators like Barry acknowledge that it is difficult to authenticate very early works or very late works of artists.

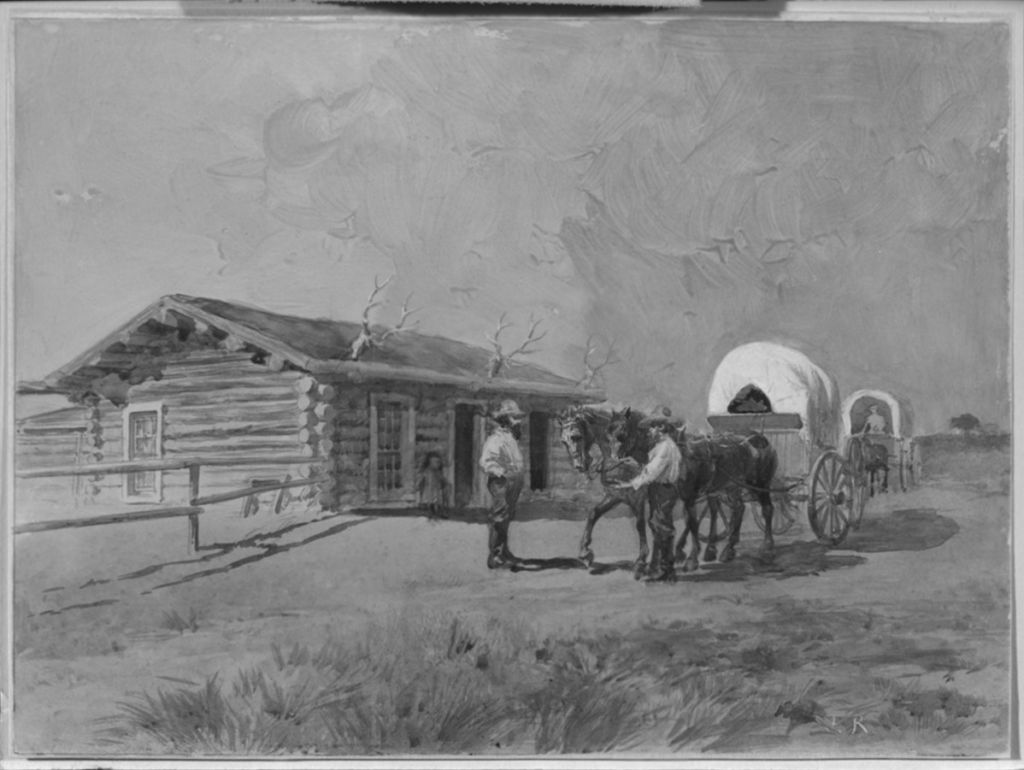

One of the many tools conservators employ in their lab is infrared reflectography, which allows one to examine any underdrawings. Unfortunately, Ms. Barry did not discover much underdrawings in The Way Post. Instead, one can get a better sense of the underdrawings with the naked eye, as the graphite is visible through the watercolor.

Infrared reflectogram mosaic, Attributed to Frederic Remington, The Way Post, c.1881, Sid Richardson Museum

The Way Post, detail

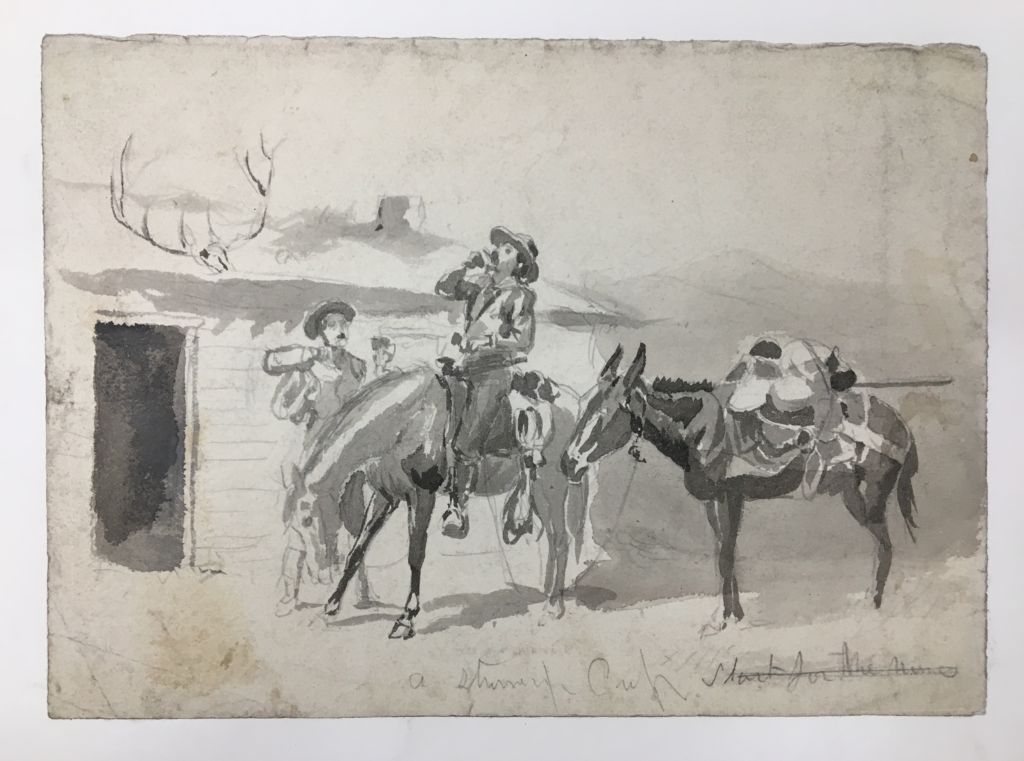

As mentioned in a previous blog post, the similarities between The Way Post and the work of one of Remington’s contemporaries, William de la Montagne Cary, is striking. Like Remington, Cary was also a Western illustrator around the same time period (1840-1922). Compare The Way Post with Cary’s The Strong Cup from the Gilcrease Museum’s collection, which is similar in subject, media and size.

William de la Montagne (1840-1922), A Strong Cup, Collection of the Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma

Other clues about the painting’s authorship are best found within the composition and painting technique itself. Note the presence of a child in the background, the inclusion of which is unusual for a Remington painting. Yet the use of a raking shadow throughout the painting, particularly under the fence, is a signature of Remington’s work. Likewise, one will note the difference in texture between the foreground washes and the opaquely painted sky – another signature of Remington’s style.

Detail of Remington’s signature, The Way Post

The painting is monogramed with Remington’s initials, F.R. While Remington did use his initials on other early works, the style of the letters in this painting is a little different. Unfortunately, Remington was not consistent with his signatures, using different colors, different styles, and even different angles. See if you can spot which signature below appears on a fake Remington painting:

If you guessed “d.”, you’re correct!

While recent studies have provided a closer look at The Way Post, attribution still remains unclear. What are the next steps? Claire Barry suggests an examination of the areas with white gouache under ultraviolet light and analyze the samples this paint with XRF and polarizing light microscopy, which are tools that would help determine if the paint used in the gouache is titanium white. Why is that important? Titanium white was not invented and produced until the 20th century after Remington’s death. Despite the continued mystery of authorship, whoever the artist of this painting may be, what’s clear is that the work exhibits an underlying quality that one can enjoy regardless.

[1] A catalogue raisonné is a comprehensive, annotated listing of all known artworks by an artist in a particular medium.

Interesting!! I would have bet money on C! The style is just so different! Love the blog!

Thanks, Diane! Yes, it can be tricky to decipher a real from a fake, even in the signatures. So fascinating!

I was able to view the outstanding Frederick Remington exhibit at the Booth Western Art Museum in Cartersville, GA yesterday afternoon. There was a large painting, portrait orientation, of a rider heading straight for the viewer. It was signed (unmistakably) “Frederck Remington”. No “i” in Frederick. I asked the exhibit attendant about it and he didn’t even feign interest. Any idea?

Good question, John. Unfortunately, I do not know the answer. However, Frederic Remington’s first name is spelled without a “k” so that would be a good giveaway that it’s not an original. ;)

I have a F.R. print that has two signatures, one in the print and another with a bucking horse on the other corner. How do I know if it is part of the print or actually signed? Thank you

That is a good question, Mrs. Knopik. I’m not familiar with Remington including a symbol like a bucking horse with his signature. In any case, the Museum does not perform identifications, authentications, or appraisals. I recommend contacting an appraiser at http://www.appraisers.org or http://www.isa-appraisers.org if you’re wanting more information about your specific print.

How do I go about seeing if a Frederick Remington signature is legitimate?

Bailey, I recommend finding an appraiser. The Museum does not perform identifications, authentications, or appraisals.

You can find a certified appraiser at http://www.appraisers.org or http://www.isa-appraisers.org.

Did F. Remington ever signed painting with last name only?

That is a good question. I believe all of the Remington paintings in our collection include both first and last name.

I bought a painting, The Stampede, in Sedona Arizona almost 20 years ago. I bought it at a Goodwill Store. I spotted it across the room, as did my friend. Sitting adjacent to other paintings, it stood out. My friend thought it was original and I don’t know. I just know it is beautiful. It has an old simple frame, is wrapped over cardboard and the staples that hold the painting within the frame are very old.

I brought it home, wrapped it in a blanket and put it behind a TV upstairs. My friend that went with me asked me 3 years ago if I got the painting checked out and told me I should because— she believes it is original. But I still didn’t think about it, I had forgotten what it was. My in-laws had a reproduction from the 60s and it is not like that one.

I ran across it, brought it down and took a damp cloth to wipe it off. When I did some greenish (I thought paint) came off on the rag so I stopped. I assumed reproduction but researched and discovered for this painting— he used chalks to create the night light— so setting out to prove it not original— could not be proven as chalk would rub off, not paint.

Second, because it is wrapped on anpiece of thick cardboard, I assumed an original would be different only to find that cardboard is what he used to wrap canvas on.

So I set out to look at signature. I found numerous signatures, none of which matched mine. Then I found the original large painting in the museum in (Oklahoma I think). And the signature is exactly the same.

So everything that I’ve noticed that made me believe it not original, with research has proven to be something unique to him or to this specific painting.

I have had three people in their 80s look at it. All of them skeptical of most things, stated immediately that they believed it to be an original, but knew for sure the frame, staples, other materials are really old. I have not carried it yet to have it authenticated because I would need to travel across the country and am not sure I could fly with it. I measured it but can’t remember exact size — but about 20” tall and 30” wide. So I am now getting ready to drive with it. I have seen the value of some original work but not since2016 or before.

It appears it could be valuable, but I’m not sure. Could you telltell me a) if it is even possible that I could have an original? B) anything else I might look at to further identify authenticity c) if original, it’s possibke worth

Another thing —if this is important, I believe I read that he numbered these and there is a number in the corner on the back. I turned it over and it appears the people at the goodwill store covered a spot on the back and then wrote the price below this spot. Leading me to believe it was a number marked through so there wouldn’t be confusion about price.

I know the odds of this being valuable are low, but if a reproduction someone went to great lengths, painting with chalks, used really old materials and signed a perfect signature. Also I’ve compared it to reproductions and the colors are different. This one is more like the colors in the original at the museum. More greenish yellow than blue. Based on what I’ve read this is something he worked hard to achieve and it took chalks to get the night rain light— which is why he used chalks.

I have compared small spots of unique detail, detail in one spot to detail in adjacent spots, etc. I have not found a difference.

Another question? Where would I go to get it authenticated? And if it turns out to be original, where should it be sold?

I have not tried an online appraiser because a) I think it will have to be done in person and b) Safety. I moved it from my home for security reasons.

Third

Sue,

It sounds like you’ve been through quite a ride with this piece.

Unfortunately, the museum does not perform identifications, authentications, or appraisals.

You can find a certified appraiser at http://www.appraisers.org or http://www.isa-appraisers.org.

Hello,

I have recently acquired a very large Oil on Canvas old painting that appears to be by Frederic Remington.

But, no signature. Did Remington ever not sign any of his paintings?

Thank you,….John.

John,

Good question! It’s possible that the artist did not sign all of his paintings, but Remington was wary of copyright infringement since many of his works were made for reproduction in journals and magazines, thus the signature on many of his works. If you’d like to authenticate your painting, I recommend contacting an appraiser. The Museum does not perform identifications, authentications, or appraisals. You can find a certified appraiser at http://www.appraisers.org or http://www.isa-appraisers.org.