*The following is researched and written by Dr. Mark Thistlethwaite, Professor of Art History Emeritus, Texas Christian University*

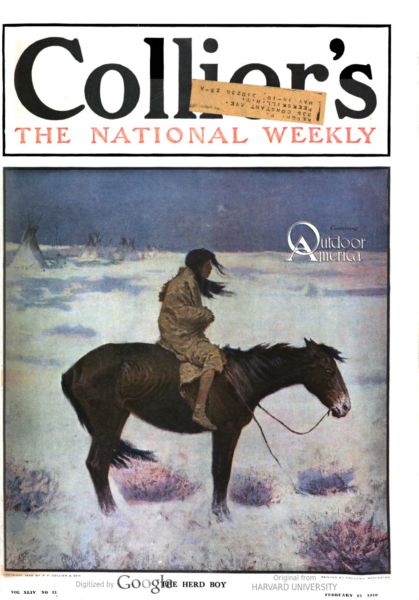

Among the striking artworks currently on view in the exhibition Night and Day: Frederic Remington’s Final Decade, I found The Herd Boy (ca. 1905; fig. 1) to be particularly intriguing. I am impressed by how Remington plays off the details of the shivering young man mounted on his scrawny horse against the vagueness of the vast frozen landscape and how the amazingly frenetic brushwork of the windswept foreground contrasts the resigned rootedness of the horse. I am also captivated how Remington suggests a liminal moment between night and day to let us determine that narrative element. A final aspect of The Herd Boy that intrigues me is the composition’s inclusion in an advertisement. Frederic Remington’s relation to advertising is what I wish to explore in this blog.

Fig. 1. Frederic Remington, The Herd Boy, ca. 1905, The Hogg Brothers Collection, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

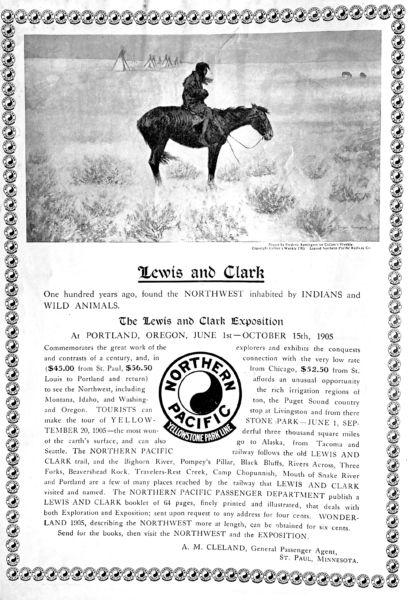

As The Herd Boy’s wall label indicates, the picture headed a full-page print ad for the Northern Pacific Railway’s excursions to the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition in Portland, Oregon (fig. 2). The 1905 ad’s text does not mention the painting, which was part of Remington’s work for Collier’s magazine before being purchased by the railway and exhibited at the Lewis and Clark exposition. Like other railroad companies of the time the Northern Pacific line produced illustrated posters and brochures and collected artworks as promotional material to entice passenger travel. However, unlike the typical advertisement that glamorized train travel by offering spectacular renderings of Western scenery, this 1905 ad presents a melancholic view that evokes the passing of the Old West. The ad’s first sentence indicates that the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition is not only a commemoration of the explorers’ expedition but also is a display of the “conquests and contrasts of a century.” In the context of this ad, Remington’s art offers, to paraphrase the cultural anthropologist Renato Rosaldo, a nostalgic image of the passing of what Americans themselves had transformed.[1]

Fig. 2. Northern Pacific Railway ad featuring The Herd Boy, in Collier’s Weekly, June 17, p. 2, 1905, Sid Richardson Museum, Fort Worth

Fig. 3. Frederic Remington, The Apache War–on Geronimo’s Trail, cover for Harper’s Weekly, January 9, 1886, Library of Congress

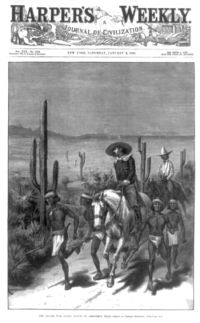

The Northern Pacific Railway’s inclusion of a work of fine art by a renowned artist in its ad signaled the company’s progressive attitude toward advertising. The British soap company A. & F. Pears was the first advertiser to reproduce a famous artist’s oil painting for promotional purposes when in 1886 it published Sir John Millais’ A Child’s World (renamed Bubbles for the ad ). Coincidently, 1886 was the year in which Frederic Remington’s first “real illustration” (in his words) was published as the cover for the January 9 issue of Harper’s Weekly (fig. 3). Remington’s timing was fortuitous since it occurred during a period recognized as the Golden Age of Illustration, the beginning of advertising’s modern professionalization, and the heyday of colorful posters and profusely illustrated magazines. A perfect artistic storm for an emerging artist!

The era’s radical changes in printing technologies are evident when comparing the 1886 Harper’s Weekly cover with a posthumous one for Collier’s (fig. 4). These covers display the move from manual wood-engraving illustrations to photomechanical halftone ones. In terms of art, both covers manifest the new advertising field’s elevation of visual imagery. “A picture that means something and if cleverly drawn doubles the pulling power of your ad in nine cases out of ten,” claimed an 1894 ad (appropriately, with an illustration) in the professional journal Art in Advertising.[2] Magazine covers were considered a form of advertising meant to entice customers. Illustrated covers functioned as mini-posters to attract attention and pique interest.

Fig. 4. Frederic Remington, The Herd Boy, cover for Collier’s magazine, February 12, 1910, Public Domain, Google-digitized

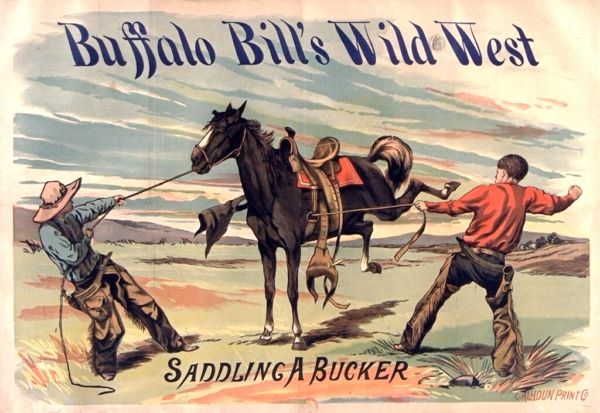

Remington’s imagery appeared in advertising posters throughout his career. Early examples are those publicizing Buffalo Bill’s Wild West when it appeared in Paris in 1889 (fig. 5). Remington was not credited with the imagery, which was copied from illustrations he had created for Theodore Roosevelt’s article “Ranch Life in the Far West,” published in the Century Magazine in February, 1888 (copyright protection for posters and advertisements went into effect in 1903). Nevertheless, newspapers and magazines in the United States and France recognized as Remington’s work and praised it.

Fig. 5. After Frederic Remington, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West–Saddling a Bucker poster, 1889, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, Public Domain

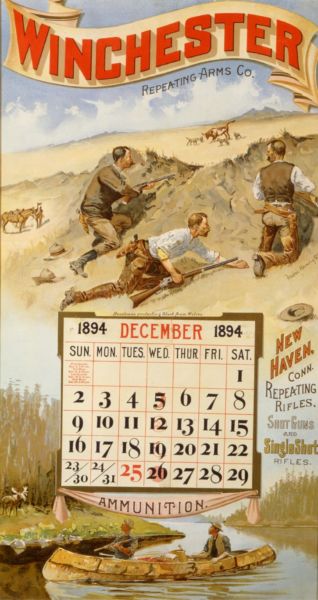

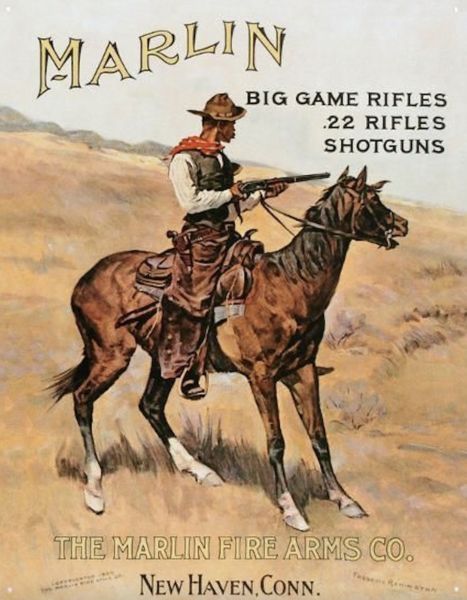

In addition to posters, Remington’s artwork appeared on promotional calendars, such as an 1894 one for Winchester Repeating Arms Company (fig. 6). Here two Remington watercolors—Ranchmen Protecting the Stock from Wolves (ca. 1893) and A Surprise Party (ca. 1893) frame the calendar. Another rifle company–Marlin Firearms–appropriated Remington’s His Last Stand for the cover of its 120-page catalogue (figs. 7–8). Today, a silhouetted figure of the mounted rifleman serves as the Marlin company’s logo.

Fig. 6. Frederic Remington, Winchester Repeating Arms Co. calendar, 1894, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming

Fig. 7. Frederic Remington, His Last Stand, ca. 1890, Sid Richardson Museum, Fort Worth

Fig. 8. John Scott after Remington, Marlin Firearms Co. Catalogue cover, 1900, https://remington.centerofthewest.org/Artworks/img/3361

Fig. 9. Frederic Remington, Smith & Wesson ad in Saturday Evening Post, February 7, 1903, p. 19, https://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/flipbooks/issues/19030207/, Public Domain

In 1902, Remington produced four works for a Wesson & Smith Revolver advertising campaign. One of them, The Last Stand (fig. 9), visualizes why, according to the ad, “After exhaustive tests the United States Government has put Smith & Wesson Revolvers in the hands of the soldiers. Soldier and civilian alike meet dangerous needs with the confidence that no other revolver but a Smith & Wesson gives.” When an ad such as this appeared, as it did in the February 7, 1903 issue Saturday Evening Post, its context included several other ads on the page vying for the reader’s attention (fig. 10). In this case, below the Smith & Wesson ad were those promoting automobiles, aluminum cooking utensils, and egg incubators. Also on the same page was an advertisement for the Remington Typewriter Company. It is very surprising that Frederic Remington’s art was never included in ads for Remington typewriters, Remington bicycles, and Remington rifles, three highly advertised products of his day.

Fig. 10. Advertisements in Saturday Evening Post, February 7, 1903, p. 19, 19, https://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/flipbooks/issues/19030207/, Public Domain

Fig. 11. Eastman Kodak Co. ad in The American Monthly Review of Reviews, December, 1902, n.p., Public Domain, Google-digitized

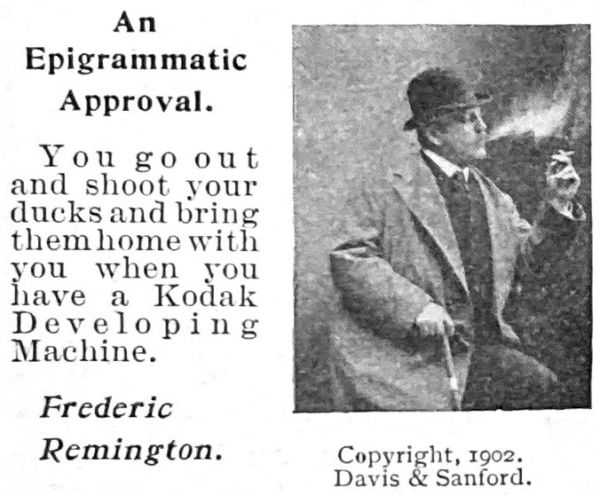

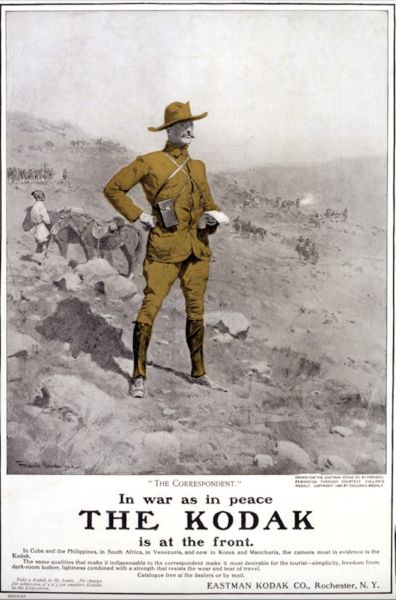

Frederic Remington’s celebrity status is made manifest when he was included in an Eastman Kodak ad of 1902 as one of the “important people” offering an “important” opinion on the company’s film developing machine (fig. 11-12). Among the other notables appearing in the ad are Alexander Graham Bell and the photographers Alfred Stieglitz, Rudolf Eickemeyer, Jr., and Zaida Ben Yusuf. It is ironic that Remington is included in this cohort of spokespersons since, while he certainly often used photographs as source material for his compositions, he (and his admirers, even more so) played down his use of the camera. For instance, his illustration The Correspondent for a 1904 Eastman Kodak print ad (fig. 13) indicates that it was drawn for the company but does not mention it was based on a photograph (now in the collections of the Frederic Remington Art Museum, Ogdensburg, New York). Remington’s image of an adventurous roving reporter was a departure from Eastman Kodak’s ads that typically featured the chic Kodak Girl (fig. 14), who had been the star of the company’s ads since 1893.

Fig. 12. Detail of Fig. 11

Fig. 13. Frederic Remington, The Correspondent, Eastman Kodak Co. ad in Collier’s Weekly, April 23, 1904, back cover, Public domain, Google-digitized

Fig. 14. Eastman Kodak Co. ad in Life, May 12, 1902, p.382, Public Domain, Google-digitized

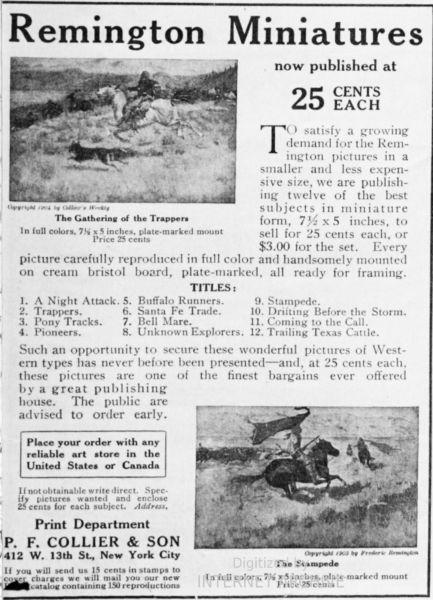

During Remington’s final decade, his paintings and illustrations were advertised frequently in national magazines as well as newspapers across the country (figs. 15-16). Reproductions of his works were available for purchase in a variety of sizes and prices. After 1903, when he secured a lucrative contract with Collier’s magazine, the journal, which outranked other top-selling magazines in terms of the numbers of ads per issue, prolifically advertised Remington’s art (figs. 17-18).[3] However, as the decade wore on, Collier’s began to experience a decrease in advertisers. Several of Remington’s diary entries in 1908 express his concern over Collier’s dwindling number of advisements, which certainly affected the revenue of the magazine as well as his.

Fig. 15. Detail of Abraham and Straus department store ad in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle,

February 5, 1903, Public Domain

Fig. 16. Cosmopolitan magazine ad in the San Francisco Examiner, October 4, 1905, p. 8, Public Domain

Fig. 17. Ad for Remington Pictures in Collier’s, May 20, 1905, p. 28, Public Domain, Goggle-digitized

Ad for Remington Miniature in Collier’s, April 24, 1909, p. 35, Public Domain, Goggle-digitized

Remington’s concern was warranted. He wrote in his diary on January 1, 1909: “Colliers [sic] advertise me exclusively although I am fired. . . . They have no advertising. I am no longer on a salary and fully embarqued [sic] on the uncertain career of a painter.” Despite his losing the market opportunities that Collier’s provided for the sale of his art, his separation from the magazine coincided with his new recognition as a serious, significant painter, as the exhibition Night and Day: Frederic Remington’s Final Decade demonstrates.

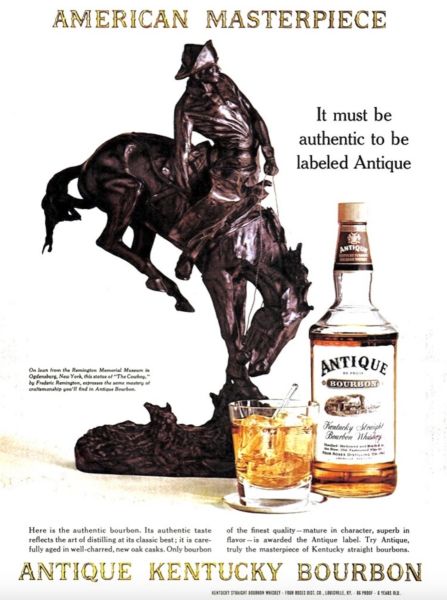

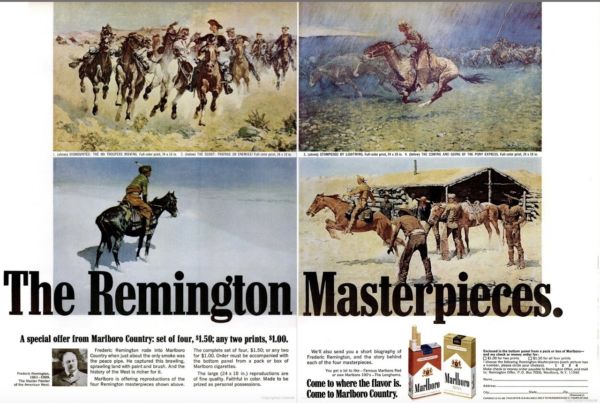

The power of Remington’s art to express an image of the Old West that many Americans have perceived to be both authentic and mythic has continued to be mined by advertisers long after his death in 1909 (figs. 19-20). Makers of whiskey have been particularly drawn to associate Remington’s art to their products, which is something worth pondering. In whatever ways later advertisers have appropriated Remington’s work, they have recognized and perpetuated Remington’s notion that his “cowboys are cash.”[4]

Fig. 19. Antique Kentucky Bourbon ad, Life, September 22, 1961, p. 52, Life Magazine Digital Archive/The New York Public Library, https://books.google.com/books/about/LIFE.html?id=R1cEAAAAMBAJ, Public Domain, Google-digitized

Fig. 20. Marlboro ad, Life, June 28, 1968, pp. 46-47, Life Magazine Digital Archive?The New York Public Library, https://books.google.com/books/about/LIFE.html?id=R1cEAAAAMBAJ, Public Domain, Google-digitized

[1]. Renato Rosaldo, “Imperialist Nostalgia,” Representations 26 (Spring 1989): 108.

[2]. “The ‘Art’ Part,” Art in Advertising 9 n.2 (June 1894): 151.

[3]. Amy Scott, “Printing the Place: Mass Media and the Arid West, 1840-1910,” (PhD diss., University of California, Irvine, 2013), 138, https://www.proquest.com/docview/1413316729/fulltextPDF/E426A250B6AE4A56PQ/126?accountid=7090.

[4]. Frederic Remington in a letter to Poultney Bigelow, 1895, in Allen P. Splete and Marilyn D. Splete, Frederic Remington–Selected Letters (New York: Abbeville Press, 1988), 269.

Thank you to Mark Thistlethwaite Professor of Art History, Emeritus, Texas Christian University for the research he has done on Frederic Remington. This was wonderful. Thank you also to Sid Richardson Gallery for showing this.