Charles M. Russell, When Blackfeet and Sioux Meet, 1908, Oil on canvas, 20 1/2 x 29 7/8 inches

In our ongoing efforts to learn more about the various American Indian cultures represented in our collection – like the Blackfeet depicted in many of Charlie Russell’s paintings – The Sid recently hosted a training for our docent volunteers led by Dr. Michael Wise, an Assistant Professor of History at the University of North Texas, where he specializes in the history of the American West.

Dr. Wise has studied many aspects of the food histories and cultural environments of the American West, including the 2016 publication Producing Predators: Wolves, Work, and Conquest in the Northern Rockies, a book about the history of wolf eradication and the cattle industry. In addition, he is the editor of the recently completed volume, The Routledge History of American Foodways, a twenty-five-chapter compendium on the environmental and cultural histories of food in the United States. Dr. Wise is currently working on a historical account of food and colonialism in Native North America spanning the last five centuries. More specific to our collection is his chapter, “The Place that Feeds You: Allotment and the Struggle for Blackfeet Food Sovereignty,” in the 2017 book titled Food Across Borders. During our training, Dr. Wise talked with us about the Blackfeet and their evolving relationship with food.

Dr. Wise has studied many aspects of the food histories and cultural environments of the American West, including the 2016 publication Producing Predators: Wolves, Work, and Conquest in the Northern Rockies, a book about the history of wolf eradication and the cattle industry. In addition, he is the editor of the recently completed volume, The Routledge History of American Foodways, a twenty-five-chapter compendium on the environmental and cultural histories of food in the United States. Dr. Wise is currently working on a historical account of food and colonialism in Native North America spanning the last five centuries. More specific to our collection is his chapter, “The Place that Feeds You: Allotment and the Struggle for Blackfeet Food Sovereignty,” in the 2017 book titled Food Across Borders. During our training, Dr. Wise talked with us about the Blackfeet and their evolving relationship with food.

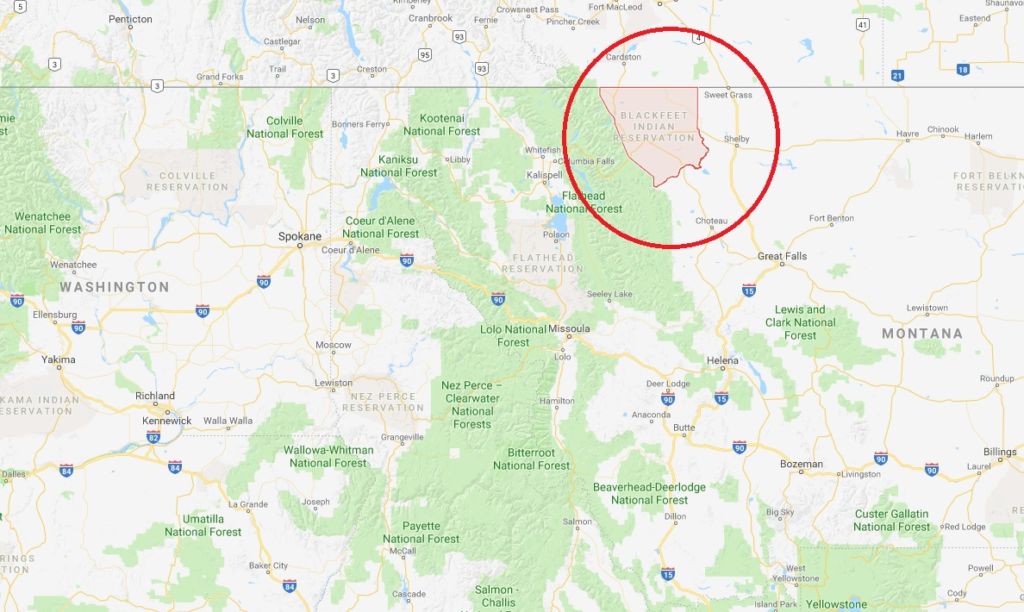

The Blackfoot Confederacy is the collective name for the four bands that make up the Blackfeet (or Blackfoot) people. Three of the four bands live in Canada, but our discussion centered primarily on the Southern Piegan/Blackfeet (or Amskapi Pikuni) who reside in Montana. Historically, the Blackfeet are frequently represented as “hunters” in Euro-American art and literature. However, they subsisted on more than just bison, trading a substantial amount of meat for corn, squash, and other agricultural products with the neighboring Mandan, Crow, and other indigenous people. Likewise, the Blackfeet followed their own form of horticultural practices, though these practices may not resemble our traditional ideas of agricultural systems.

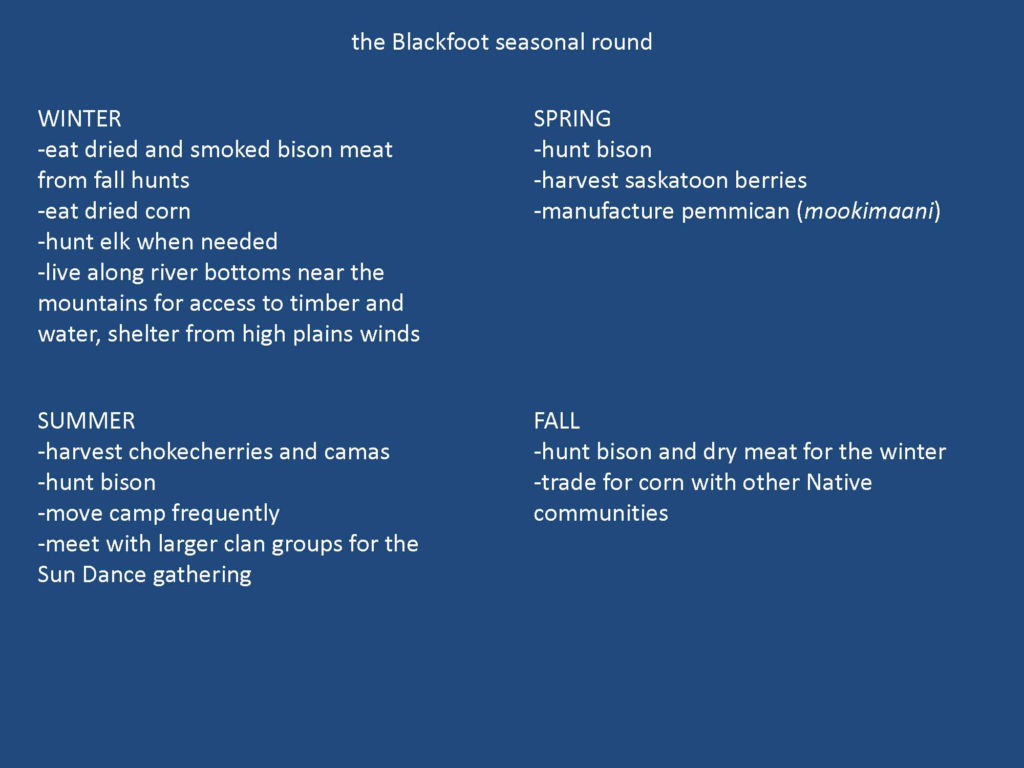

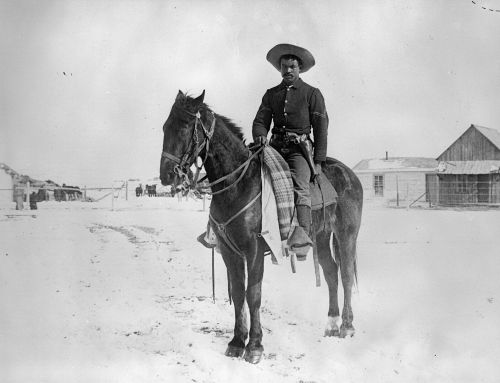

Blackfoot Season Round from Dr. Michael Wise

Prior to life on reservations, the Blackfeet based their foodways on a seasonal round, with families traveling 1-2,000 miles annually to as many as 15 campsites across an approximately 10,000 square-mile area. Despite moving to various locations throughout the year, the term nomad is not wholly accurate in describing the Blackfeet, as they never wandered, but instead knew to where they were traveling, often returning to the same place. (The Blackfoot word for “home” is auasini, which translates to “the place that feeds you.”) At some of these locations, the Blackfeet would remove non-edible plants to allow for the growth of selective wild vegetables in that area. Likewise, they practiced seasonal burning of plains grasses to better direct bison near buffalo jumps, or pishkun (a practice in which the hunters would drive a herd of bison over a cliff).

Alfred Jacob Miller, Hunting Buffalo, 1858-60, The Walters Art Museum, 37.1940.190

The Blackfeet didn’t just survive off the land; they thrived! They developed specifics tastes, knowing which season produced the bison meat they preferred, for example. And with that bison, they created ingenious ways to use every part of the animal. The Blackfeet also discovered how to make food that was long lasting and calorically dense. A food product like pemmican – made from bison flesh, Saskatoon berries, and tallow – was a necessity for their intense, calorie-burning travelling lifestyle.

By the 1870s, most of the Blackfeet had moved onto a reservation, the boundaries from which they were not allowed leave in order to hunt. Instead, the federal government allocated herds of cattle turning the Blackfeet Reservation into a ranch that would feed into the national industrial meat system. A slaughterhouse was erected and employed Blackfeet men, paying them not in cash but ration tickets. Prior to reservation life, it was traditionally the role of the Blackfeet women to slaughter and butcher the bison. On The Blackfeet Reservation, the women transformed from butchers into bakers, whose products helped feed the reservation agents.

Eventually, tribal ranchers adapted traditional cooperative livestock raising practices with the creation of the Piegan Farming and Livestock Affiliation (PFLA) in order to fend off the ongoing redistribution of land since the implementation of the Dawes Act, which had divided tribal land into allotments for individual Blackfeet. PFLA recast the individualizing imperatives of allotment with communal farming, which allowed the Blackfeet to regain a bit of control over their foodways once again.

Leave A Comment