What happens when a painting leaps from the canvas onto the silver screen? That is the story at the heart of a recent lecture at the lecture Sid Richardson Museum, in which our director, Scott Winterrowd, traced the fascinating journey of Remington’s 1897 painting A Misdeal—a smoky, tense card game gone wrong—through Hollywood history, illuminating how Western art and cinema became deeply intertwined.

Remington’s A Misdeal is not attached to any specific story, yet it brims with narrative potential. Gunsmoke lingers in a dimly lit saloon. Wounded players slump at the table, with one figure still standing at center. The painting invites viewers to imagine betrayal, violence, and consequence. More than a static image, it foreshadows the barroom showdowns that would become staples of the Western film genre.

Frederic Remington, “A Misdeal,” ca.1897, Oil on canvas, Private Collection

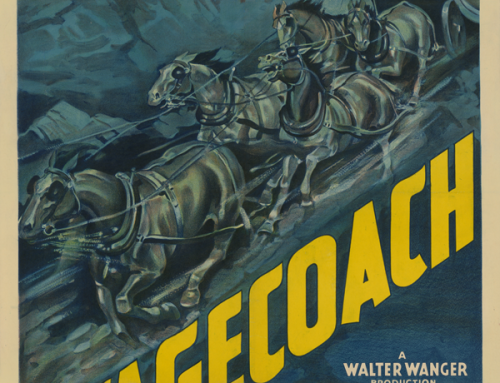

Remarkably, less than a decade after Remington’s death, A Misdeal appeared on screen. In John Ford’s 1918 silent Western Hell Bent, the painting comes to life. A character studies an image of the work, and as the camera zooms closer, the painted figures animate into action, igniting the film’s storyline. For Ford—later the director of classics like Stagecoach and The Searchers—Remington provided not just visual inspiration but a cinematic template.

Still from John Ford’s movie Hell Bent featuring the painting A Misdeal by Frederic Remington.

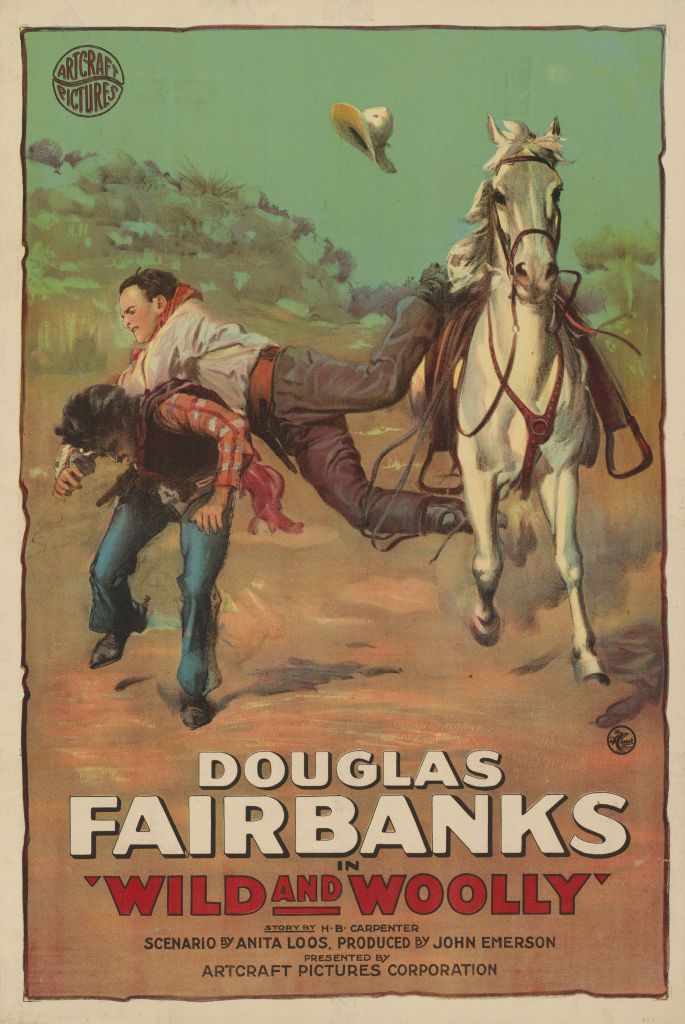

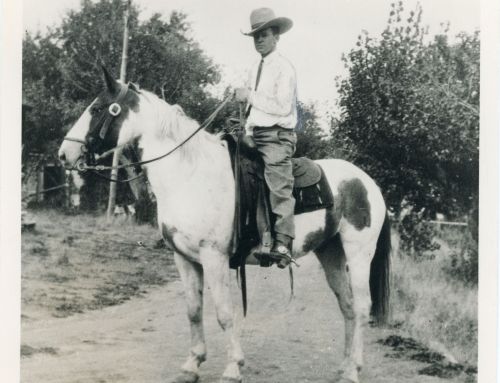

Ford wasn’t alone. Silent film star Douglas Fairbanks collected Remington’s art and even recreated scenes from paintings like His First Lesson and Fight for the Water Hole in his films. At an unknown date, Remington’s A Misdeal came into Fairbanks’s collection, and it was displayed at Pickfair (the legendary estate he shared with Mary Pickford). By midcentury, the work would be acquired by producer Hal Wallis, best known for Casablanca and True Grit.

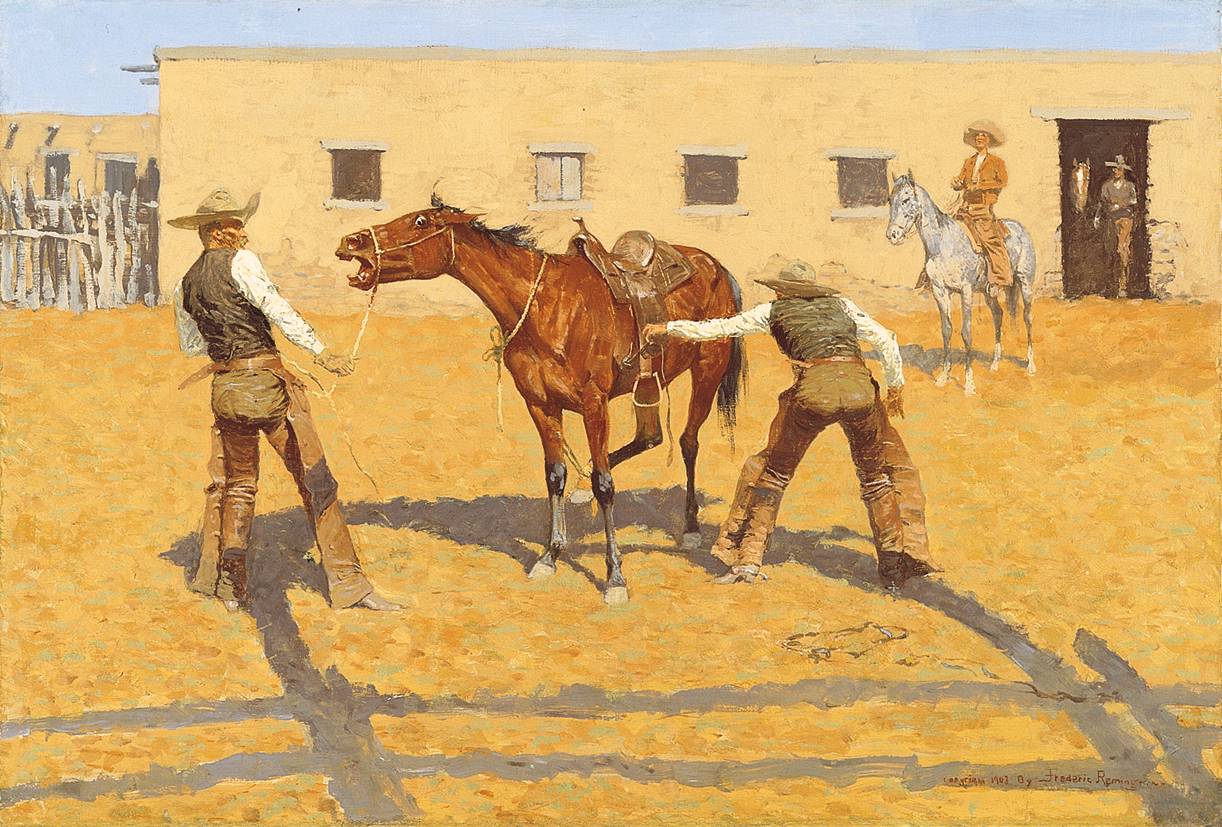

Frederic Remington, His First Lesson, 1903, Oil on canvas, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, 1961.231

Wild and Woolly Movie Poster, The H. C. Miner Litho. Co. N.Y., Lithograph, 1917, Poster collection, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, 70255991

Our current exhibit, The Cinematic West: The Art That Made The Movies, highlights how Remington and Charles Russell both influenced John Ford’s vision of the American West. While Remington’s dynamic compositions inspired Ford’s framing, Russell’s imagery and storytelling equally shaped his cinematic eye. When Ford filmed, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, he admitted to trying to capture scenes as Remington would have sketched them.

The influence extended beyond film sets to Hollywood culture itself. At Pickfair, Western paintings hung in a recreated saloon, where stars like Charlie Chaplin gathered. Later, Wallis collected seven works by Remington while he was working on the film, Gunfight at OK Corral. He would live with these paintings at his estate in Van Nuys and later at one of three residences he had between Beverly Hills, Malibu and Palm Springs.

After decades in private collections in Southern California, A Misdeal eventually made its way to Texas, where it is now on loan to the Sid Richardson Museum’s exhibition The Cinematic West: The Art that Made the Movies. Its long journey—from Remington’s easel to Ford’s silent Western to Fairbanks’s and Wallis’s homes—underscores how Western art has continually shaped and been shaped by popular culture. If you want to learn more details behind the story tracing the journey of Remington’s A Misdeal, check out the recording of our lecture program on YouTube.

Douglas Fairbanks Jr. and Mary Pickford at Pickfair Costume Party, 1933, Mary Pickford Private Foundation

In sharing this story, Winterrowd reminds us that images hold power. Remington’s brushstrokes helped invent the way we see the West, not just on canvas but in the moving pictures that defined American identity for generations. The tale of A Misdeal is more than art history. It’s a reminder of how cultural icons are created, circulated, and remembered. And it shows that a single painting can ripple far beyond the walls of the saloon it depicts, shaping the myths of the West on screen and in our collective imagination.

Leave A Comment