What happens when the heroes and villains of Western film trade places — when the Comanche become the storytellers, not the stereotypes?

The Sid Richardson Museum’s exhibition The Cinematic West: The Art That Made the Movies explores how artists and filmmakers shaped our visions of the American frontier. Yet beyond the painted canvases and silver screens lies another story, one told by those who have long been left out of the frame or shown through someone else’s lens. Through his research and creative work, Dr. Dustin Tahmahkera, a scholar, playwright, and citizen of the Comanche Nation, illuminates the vital role of Comanche people in shaping cinema itself.

Tahmahkera’s scholarship reframes Western film history to center Indigenous agency, revealing how Comanche actors, filmmakers, and storytellers have participated in and transformed the medium from the silent era to today. His work invites us to see Westerns not as a closed chapter of the past, but as a living dialogue between image and identity, where Native voices continue to reclaim and redefine how the West is seen.

Cinematic Comanches: The Lone Ranger in the Media Borderlands by Dustin Tahmahkera, University of Nebraska Press, 2022

Reframing the Story

Western art and film have long shaped how audiences imagine the frontier. Artists like Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell captured scenes of conflict and conquest that inspired early filmmakers, giving rise to Hollywood’s enduring myth of cowboys and Indians.

But as Tahmahkera reminds us, many popular narratives suggest the Comanche story ended in 1875. His scholarship reframes that story, showing instead how Comanches have continued to shape cinema from the silent era to today, asserting what he calls a “legacy of agency.”

Agency, in this context, means decision-making power: the ability to define how one’s people and history are represented. From Quanah Parker’s early appearance in silent film to contemporary Native filmmakers, Tahmahkera traces a lineage of Comanche artists who have worked both within and beyond Hollywood to tell their own stories.

Quanah Parker: From History to Screen

The story begins with Quanah Parker—Comanche leader, diplomat, bridge builder, and Tahmahkera’s great-great-great-grandfather. By the early 1900s, Quanah was known for his ability to navigate multiple worlds: honoring Comanche traditions while negotiating with the U.S. government.

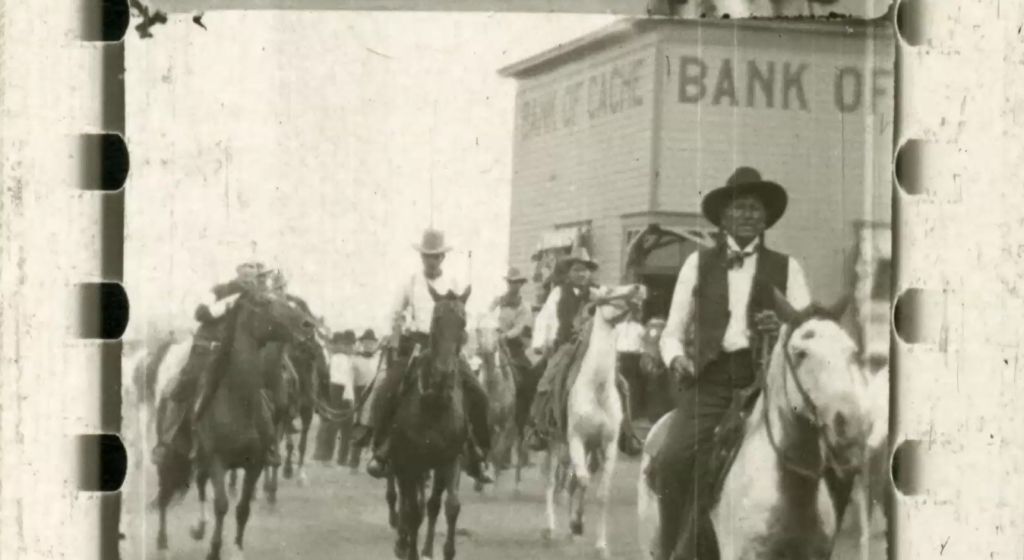

Less known is his role in early cinema. In 1908, Quanah appeared in The Bank Robbery, filmed on location in the Wichita Mountains of southwest Oklahoma, Comanche homelands. In the film, dressed in his own regalia, he led a posse on horseback to capture outlaws in what is now considered one of the first Westerns filmed with Native participants. Tahmahkera describes this as more than a cameo. It was an act of representation. “He knew what he was doing,” Tahmahkera notes, pointing out a moment in the film when Quanah glances directly at the camera—aware, amused, and in control of his image.

That quiet smirk, caught in a split second of celluloid, speaks volumes. Who’s telling the story? And who’s getting one over on whom?

Film still from the 1908 film The Bank Robbery

A Family of Storytellers

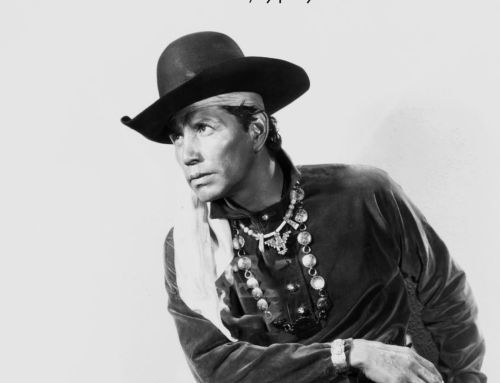

Quanah’s children followed in his footsteps. His son White Parker and daughter Wanada Parker appeared in Daughter of Dawn (1920), one of the earliest all-Native feature films. Shot in the same Wichita Mountains, the film featured Comanche and Kiowa actors performing their own stories, wearing their own regalia, not studio costumes.

Tahmahkera connects these early moments of self-representation to his family’s ongoing creative legacy. From silent film to contemporary theater, his relatives continue to work as artists, actors, and cultural consultants. He sees this as an extension of Quanah’s bridge building. These are Comanches representing Comanches, staking claims of representational jurisdiction.

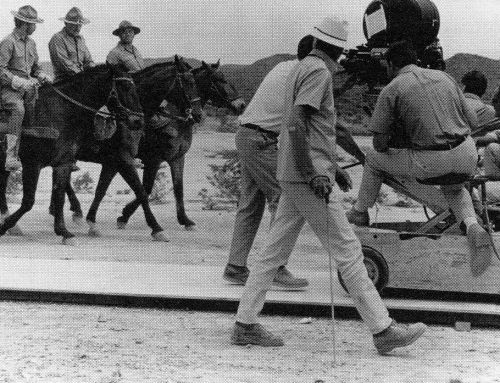

Still from 1920 film Daughter of Dawn

Reclaiming the Reel

Throughout the 20th century, Hollywood often depicted Comanches as nameless villains or faceless obstacles, i.e. “the bad Indians” opposing Manifest Destiny. Films like The Searchers (1956) distorted real stories, turning figures like Quanah’s mother, Cynthia Ann Parker, into symbols of captivity rather than representation as complex human beings.

Yet Tahmahkera finds power in the moments when Comanches reclaim the reel. He highlights Comanche filmmakers and actors such as Julianna Brannum (Ladonna Harris: Indian 101), Rodrick Rocowatchit (The Dead Can’t Dance), and the late Juanita Pahdopony, who consulted on AMC’s The Son and the Hulu feature Prey. These creators carry forward the work of telling Native history truthfully, preserving stories that have too often been told without Native voices.

Seeing the West with New Eyes

Through this lens, we are invited to look again. To see beyond familiar frames of conquest and rescue, and to recognize the creativity and humor, the diplomacy and endurance, that have always animated Comanche storytelling. For Tahmahkera, film offers a unique way to do that.

Through the flicker of early cinema and the glow of the digital screen, the Comanche story continues, not as a relic of the past, but as a vibrant, ongoing conversation about who gets to tell the story of the West.

For those interested in taking a deeper dive into this topic, you can watch Dr. Dustin Tahmahkera’s full lecture “Cinematic Comanches and a Legacy of Agency,” available on the Sid Richardson Museum’s YouTube channel.

Leave A Comment