Our current exhibition, Charles M. Russell: Storyteller Across Media, focuses on the artist’s talent and ability to tell stories – largely set in the American West – through his art. When Hollywood emerged in the 20th century and began producing Westerns, many of the great film directors like John Ford often looked to artists like Russell as a visual model for storytelling.

How does one tell the story of a Western? And what happens when the themes of the Western, this quintessential American genre, transform through changes in cultural constructions and acquire new meanings when it transcends borders?

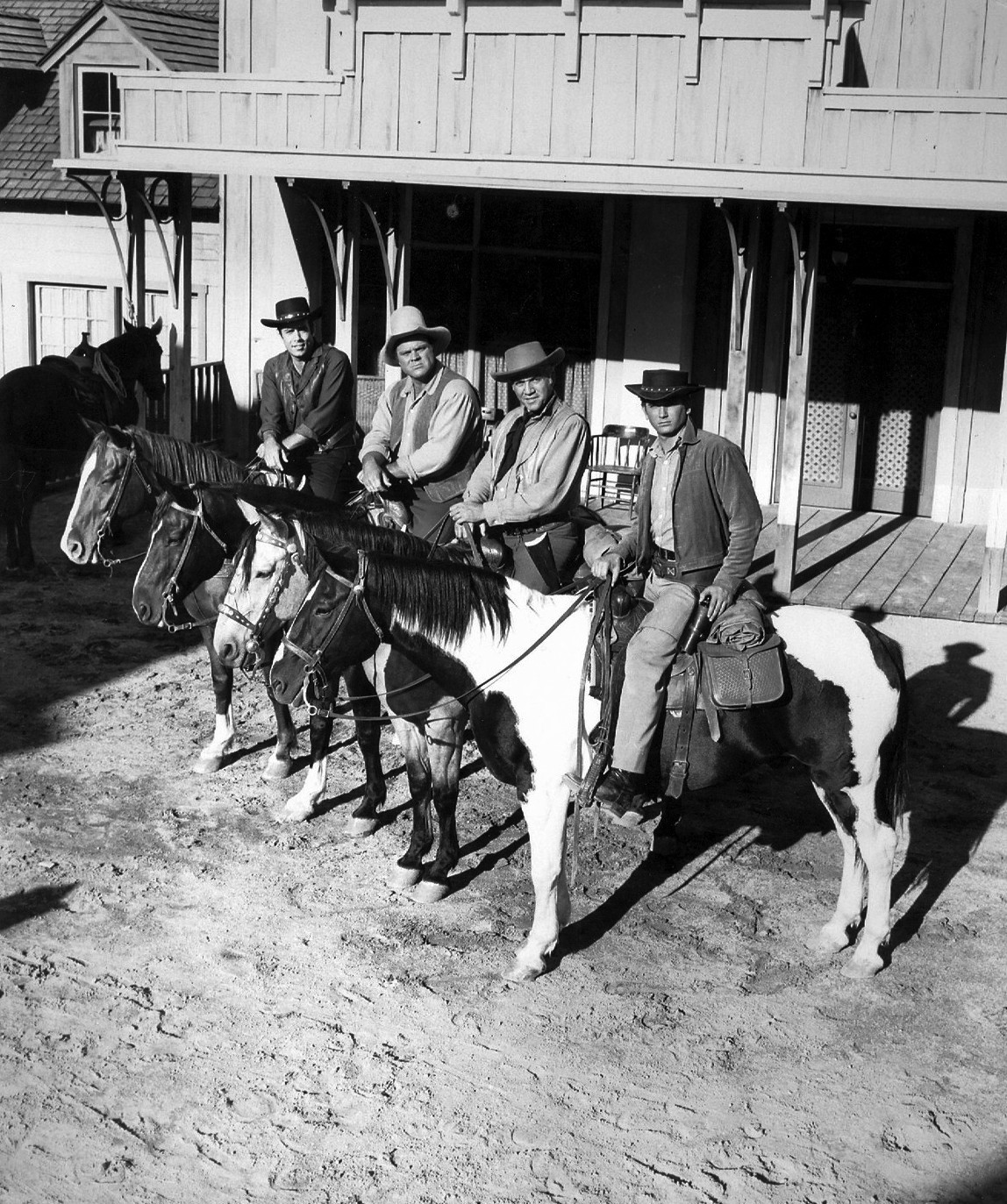

Stories of the American West spread globally as early as the beginning of the 19th century with the translation of several frontier tales, and in the late 1800s, with the travels of Buffalo Bill and his Wild West Show around the world. By the 20th century, no other American genre of entertainment was more popular on the global stage than the Western. Hollywood film and television Westerns appeared on tv screens across Europe, Latin America, and even parts of Asia. For example, the popular American Western tv show Bonanza was watched in over 62 countries and over 300 million viewers at mid-20th century. Soon film makers from outside of the U.S. started creating their own Westerns, from Poland to Italy to Argentina to Mexico.

Photo of the main cast of Bonanza. From left-Pernell Roberts (Adam), Dan Blocker (Hoss), Lorne Greene (Ben), Michael Landon (Little Joe), 1961. Public Domain.

Mexico had the most important film industry in the Spanish speaking world and played an outsized role in popularizing Westerns throughout Latin America and Spain. While there were small budding film industries in Columbia, Venezuela, Chile, the Hollywood of Latin America was in Mexico.

When scholars like Dr. Christopher Conway study Mexican Westerns, they encounter the challenge of defining what exactly constitutes a Mexican Western, as the field has a few neighboring genres that involve men in hats with guns.

One such neighboring genre is that of the comedia ranchera, roughly translated to ranch comedy. These were musical stories set on haciendas, or ranches, with charros. Charros were not the working cowboys, like vaqueros, but rather wore embroidered outfits and big hats. The comedia ranchera films often included a lot of pageantry with corridos, or ballads, singing nostalgically about a period before the Mexican Revolution.

Mannequins with charro outfits on display at the Museo del Noreste in Monterrey, Mexico.

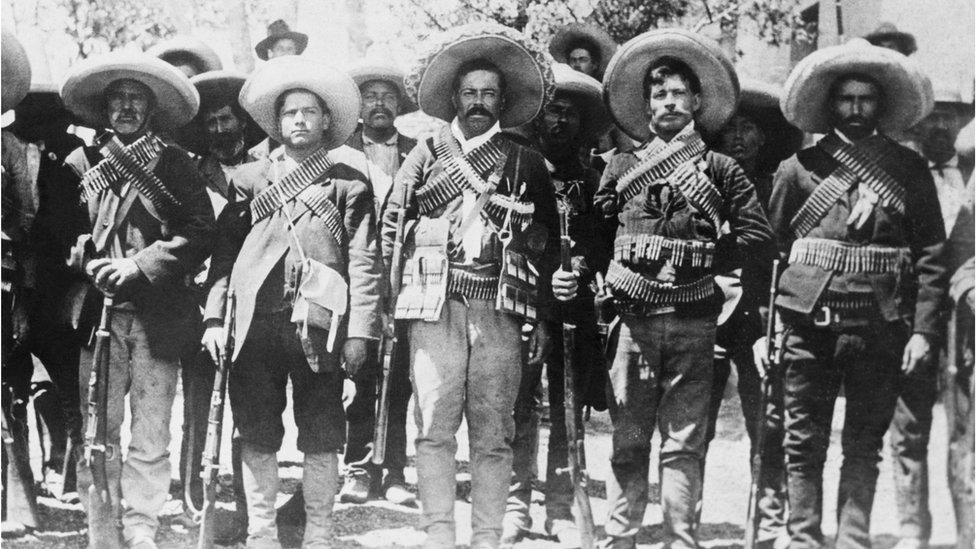

The Mexican Revolution encompasses another neighboring film genre with its own gunfighter storytelling tradition. Art house movies in Mexico about the Mexican Revolution are not Westerns. They’re a unique genre, one that is very meditative and reflective about the meaning of social change and the process of transforming society. These films were often a way of exploring what could have been, underlining the martyrdom of the heroes that could have made the country a different place.

Pancho Villa and his followers during the Mexican Revolution, 1910. Public Domain.

With these existing traditions of gunfighter stories native to Mexico, Mexican consumers were able to recognize in American Westerns something close to what they already had. Thus, film directors did not simply copy American Westerns. Rather they adopted specific motifs and then adapted the Mexican Western to fit into their national history and culture, including references to Mexican identity and folklore, looking at cultural marginalization, exploring spaces of cultural contact along the borderlands, and other unique themes.

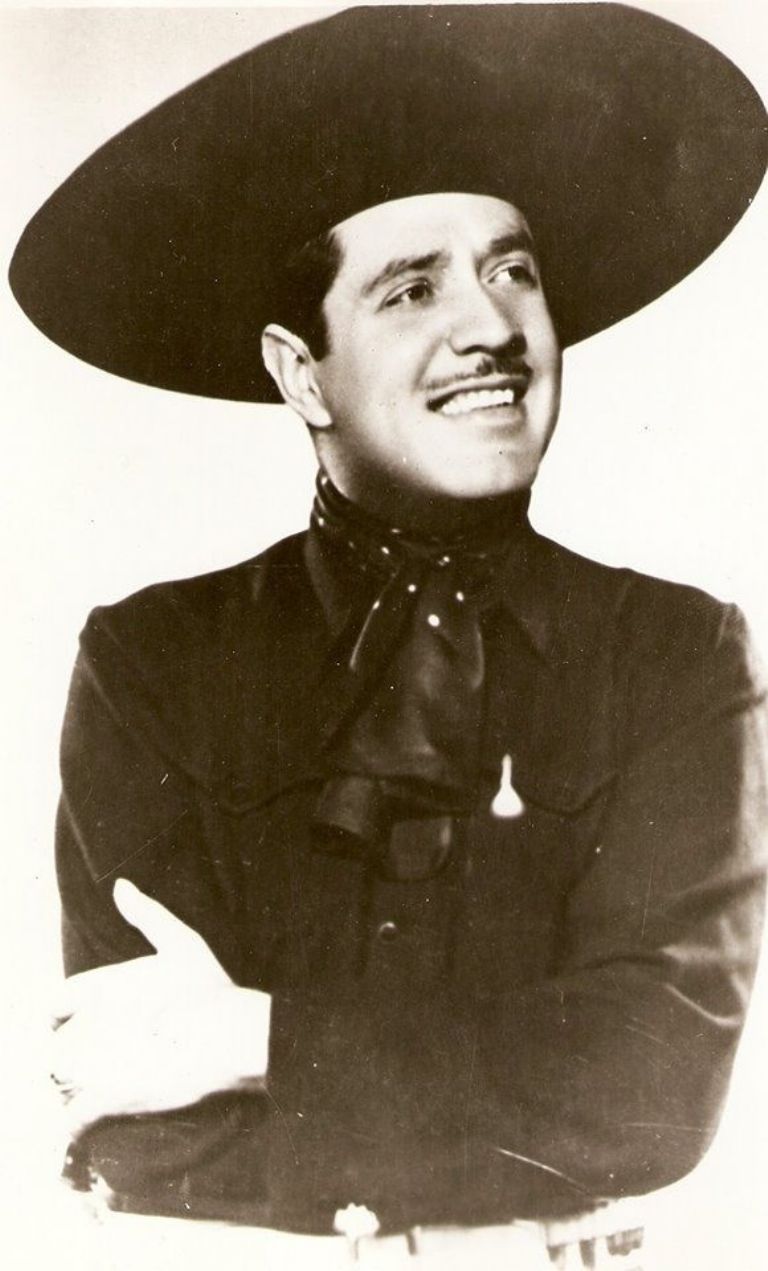

During the golden age of Mexican film (roughly 1940-1976), the biggest stars of Mexican Westerns included Raúl de Anda’s Charro Negro series of the 1940s, Antonio Aguilar’s 1950s musical Westerns, and Rodolfo de Anda’s gunfighter films of the 1960s and early 1970s.

Raúl de Anda was considered the Mexican “Cisco Kid” of the 1940s. He was a real cowboy who was also familiar with the charro life. His son became a big western star a couple of decades later. (Fun fact: Raúl de Anda visited Fort Worth in 1928 when he participated in the Stock Show and Rodeo and won 2nd place in bronco busting!)

Raúl de Anda, star of the Charro Negro films (1940-1949). Photo: Especial

Popular in the 1950s, Antonio Aguilar was an extraordinary performer. He recorded over 150 albums of Mexican music, made over 120 films, and had his own rodeo operation that took him all over Mexico and the United States. Antonio was beloved by Mexican Americans in Texas during this period.

Publicity photo for the film Ánimas Trujano (1962). Antonio Aguilar on left. Public Domain

Rodolfo de Anda, son of Raúl, began making westerns in early 1960s, at a time when Mexican Westerns were transitioning away from family-friendly films and leaning towards more gritty Westerns.

Dr. Conway teaches Mexican and Latin American literature and culture in the department of Modern Languages at the University of Texas at Arlington. His fascination with the ways in which the American Western has traveled across international borders is reflected in his published writings: Heroes of the Borderlands: The Western in Mexican Film, Comics, and Music (2019) and The Comic Book Western: New Perspectives on a Global Genre (2022).

Why study Westerns? Dr. Conway argues that they can teach us about intellectual and cultural history. Watch a Mexican Western and one can ascertain the social mentality or values of a particular moment in time.

You can learn more about Mexican Westerns by watching Dr. Conway’s recently recorded lecture at The Sid titled “How Mexican Westerns Conquered the World.”

Leave A Comment